Key Takeaways:

This region NGC 6334 (commonly called the Cat’s Paw Nebula) is rich in gas and dust. Long known to contain massive young stars, NGC 6334 lies in the constellation Scorpius, toward the galactic center at a distance of about 5,500 light-years away and practically in the plane of the Milky Way. It is the massive hottest stars classified by astronomers as type O that cause the gas surrounding them to glow in the optical spectrum.

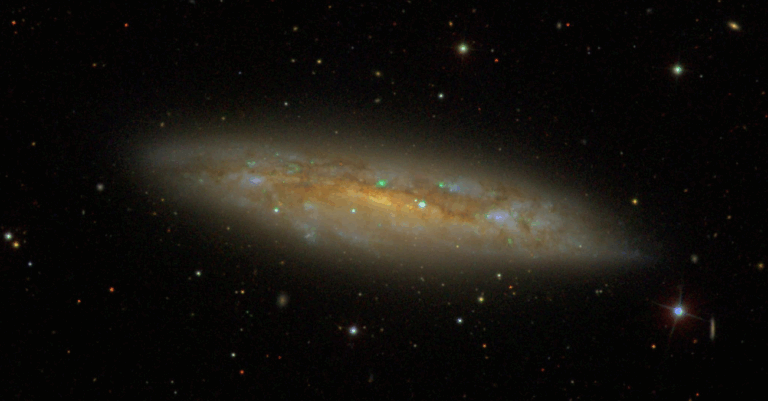

Imaging done at the National Optical Astronomy Observatory’s (NOAO) 4-meter Blanco Telescope at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile combined with data from the Spitzer Space Telescope have enabled the team to catalog much fainter young stars in NGC 6334 than has been done before. The photo shows combined images from space and ground-based telescopes. In this false-color composite, blue is assigned to a ground-based image, green to a longer-wavelength image from the Spitzer Space Telescope, and red to an even longer-wavelength image from the Herschel Space Telescope. The ground-based data were taken with the NOAO Extremely Wide-Field Infrared Imager (NEWFIRM).

Starting from the brightest and most massive stars in the region, the team has identified and cataloged all the stars down to those with the brightness of the Sun — approximately a million times fainter. Then, based on previous knowledge of the number of stars that form as a function of stellar mass, they can extrapolate to identify how many lower-mass stars exist in the region. This is analogous to saying that if we observe the adult population in a town, we can estimate how many children live in the town, even if we can’t see them. In this way, the team can derive an estimate of the total number of stars in the region and the efficiency with which stars are forming.

“The observations acquired with NEWFIRM allowed us to identify and separate out the large number of contaminating sources, including background galaxies and cool stellar giants in the galactic plane, to obtain a more complete census of the newly formed stars,” said Lori Allen from NOAO.” The team finds that the star-formation rate in this region is equivalent to 3,600 solar masses of gas becoming stars every million years — a tremendous rate even by astronomical standards.