Key Takeaways:

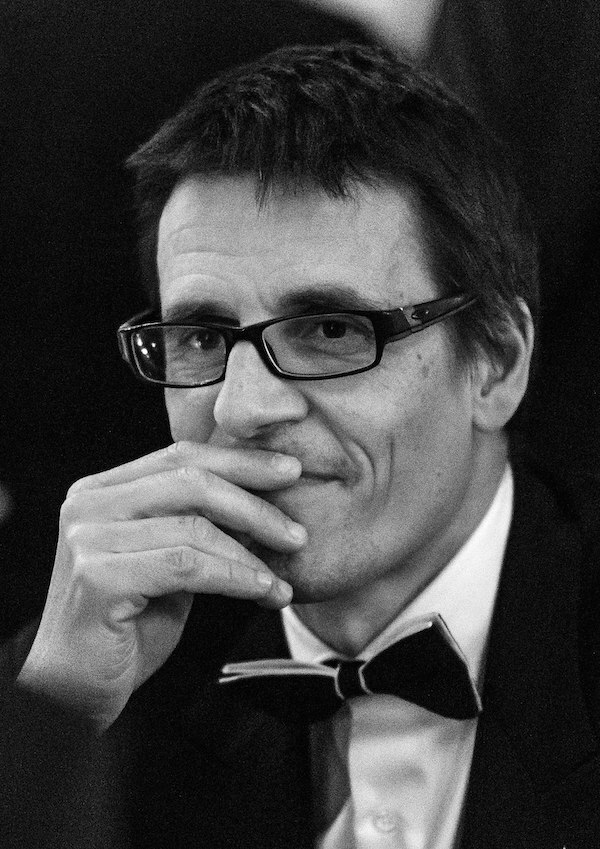

Didier Queloz is a Swiss astronomer and a professor at the Universities of Cambridge and Geneva. As one of the originators of the exoplanet revolution, he shared the 2019 Nobel Prize in Physics with Michel Mayor for their discovery of 51 Pegasi b – the first extrasolar planet found orbiting a Sun-like star.

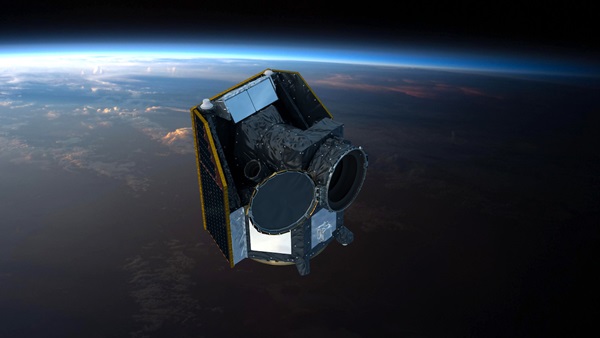

Ever since that fortuitous observation in 1995, Queloz has been at the center of innovation when it comes to the detection and measurement of exoplanetary systems. More recently, he has been directing his attention toward finding Earth-like planets, as well as understanding the origins of life. His latest project, ESA’s CHaracterising ExOPlanet Satellite (CHEOPS), has just discovered WASP-189b – one of the most extreme planets known.

In this wide-ranging conversation, we discuss his career, the phosphine discovery on Venus, and hopes for the future of exoplanetary research and the search for alien life.

Astronomy: You won the Nobel Prize in Physics in October of 2019. How do you feel about the award almost a year out?

Queloz: I am grateful for the recognition, mostly for the field. It helped give exoplanets more attention. I haven’t had a typical laureate year, though, because of coronavirus. Most winners spend all their time traveling. But because of COVID-19, I have been at home. In a guilty way, I am lucky, because I got that special time at first, and the champagne, and the media music, but then a few months later I was able to step back, spend time with my family, and work.

I feel a bit sad for this year’s Nobel laureates, because they will not be able to have the whole show that I experienced. They will still run the ceremony, but whether they will run the ceremony the way we had it, I’m not sure. The dinner is 2,000 people, enjoying great food in a great hall. I don’t think COVID-19 restrictions will allow it.

Astronomy: One of your research goals is to understand the origins of life. How does this intersect with exoplanet science?

Queloz: I feel that we cannot solve the mystery of life on Earth without trying to address it on other planets. We cannot go back to our beginning. But if we find different beginnings, different possibilities, maybe we can understand.

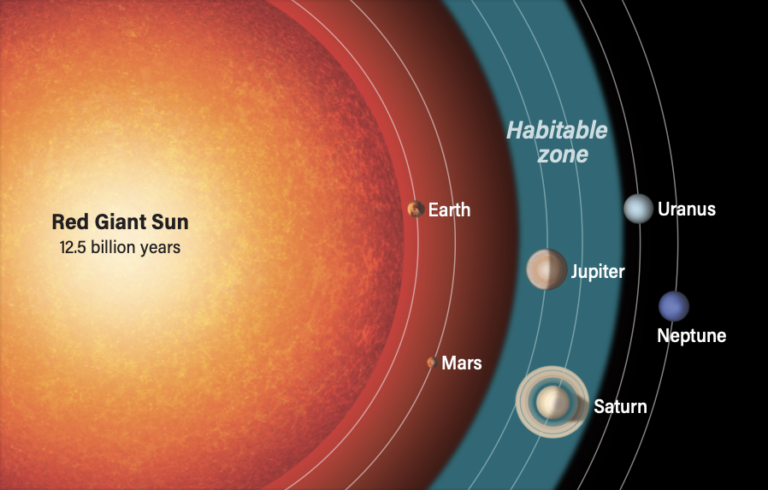

For example: Venus. A billion years ago, it was like the Earth – a beautiful blue planet. Perhaps it was living. And then the atmosphere completely changed. Now the belief is that there is no life on Venus. This might be wrong, but this is believed.

Astronomy: What do you think of the phosphine detection on Venus?

Queloz: Well, they saw phosphine twice, with two different telescopes, at two different times. So, I think it can’t be an artefact. But the way it was reduced because of Venus’s brightness is tricky. And they really need another line, because what if it is just a similar molecule?

It is very difficult when you are on the edge of science; I know this well. Your arguments are weak at first, because you do not yet have robust evidence. So, you have to play with assumptions. But sooner or later, the scientific truth prevails, because, whatever you do, anyone else should be able to do it again. The intrinsic facts build up and help you to sort it out.

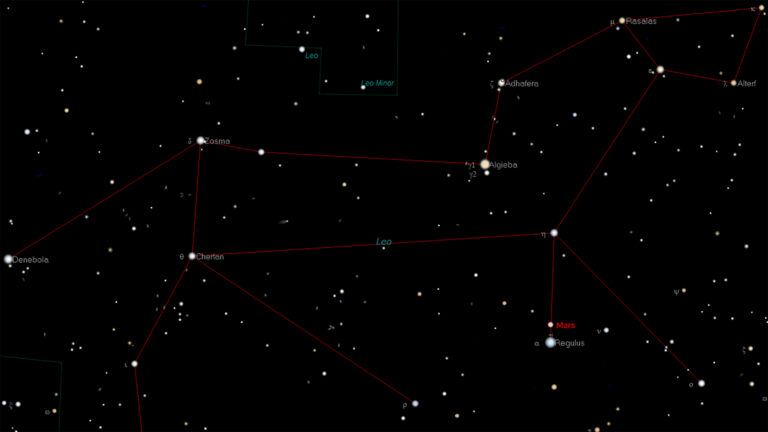

As for phosphine, I think it shows we do not know all we should about Venus. We should go there soon, perhaps with a balloon. As for life, to be honest, I think we will find it on Mars.

Astronomy: There’s been some criticism of the phosphine paper in terms of the way it was presented. Some say that life should always be the explanation of last resort in science. What do you think of that?

Queloz: I think it’s stupid. Why discard life? It reminds me of my paper [on 51 Pegasi b] 25 years ago. First, we ventured all the possible explanations for the observation. And then we said, “The only way we know to explain this bizarre object is that it is a planet.” Nobody believed what we said at that time.

I think the phosphine team has done well. They say: “It might be this, or this, but none of our calculations are a good fit.” So, it is unknown – perhaps geochemical, but possibly life. What is the matter with suggesting this? Life is nothing special. It is mysterious, not mythical. I think these critics have lost a sense of perspective.

Astronomy: You have been quoted as saying that humans will find alien life in 30 years’ time. How can you be so sure?

Queloz: My view is very simplistic on this: I think life is just chemistry. And chemistry is everywhere. If you have the right ingredients at the right time, you will have life. But how likely is it? That’s a very interesting question. Could it exist on a planet that just looks Earth-ish, [but] a bit bigger, a bit smaller? I don’t know.

There are things we think are needed to sustain life, like plate tectonics, a magnetic field to shield from high-energy ultraviolet radiation, and liquid water. Planetology will advance in the next 50 years, alongside instruments, and we should be able to measure all these parameters within a hundred light-year bubble around the Sun. And we’ll learn whether the likelihood of the conditions we have here on Earth is slim or tiny.

Even so, the galaxy is full of stars, and most of them have planets, so there must be plenty with life according to these criteria. Even if it’s one out of a million.

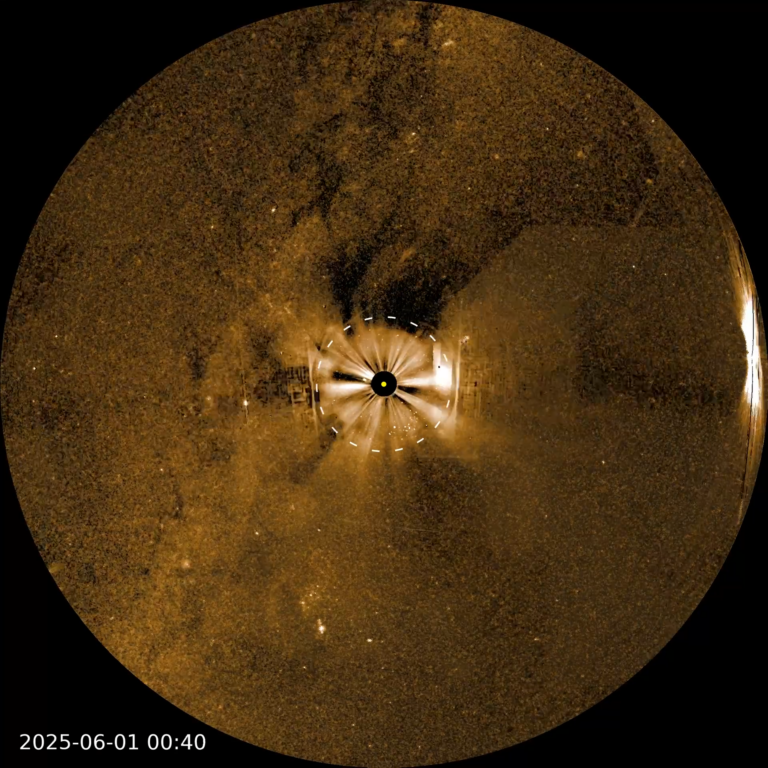

Astronomy: Tell me about CHEOPS. You were the driving force behind the mission, which just reported discovering an extremely hot Jupiter.

Queloz: I’m not on the leadership team because I can’t be bothered; that is for young people. I am content to be the father of CHEOPS. It started in 2008. I had this crazy idea while on a skiing trip that we should have a telescope specially for exoplanet researchers. Maybe it was the lack of oxygen.

At first, we failed to get the funding. But then I managed to convince my colleagues at Bern, and eventually we won the ESA call in 2012. We spent a lot of time and energy to convince Switzerland and Swiss industry that they could fly a satellite. They had the knowledge, but they were shy. We started to build it in 2013 and launched last December [2019]. And we have the first result already! And more are coming. We have seven papers in preparation right now.

Astronomy: When you started working on exoplanet detection in graduate school, it was little more than a speculative niche in astronomy. Now it’s a field in its own right, due in large part to your discovery. What are your thoughts on exoplanet science, how it’s evolved, and where it stands today?

Queloz: Every day for the past 25 years, I have seen a growing interest in the topic of planets, exoplanets, and life in the universe. We have more and more results, more and more people involved, and more and more students. All this interest multiplies itself, and now we have a large chunk of astrophysics dedicated to the science. Most of the big instruments now have a good fraction of their time spent on exoplanets.

At the beginning, I was talking to ghosts. I had to suffer, and beg for telescope time, and work very hard. Now I have a Nobel Prize, and all of a sudden, I am more reasonable than people without prizes. It was magical, how wise I became between the seventh and eighth of October last year. But fame is like music. Everyone loves music, but not all kinds, and sometimes you need quiet. I only hope it will help to build up the field towards new and exciting discoveries.