Nancy Atkinson loves space robots. They go where we can’t (yet), gather data we can’t gather, and tell us about the cosmos we can’t see, all while they fly through and orbit in and rove around the planets, asteroids, dwarf planets, moons, and more that make up our solar system.

Atkinson, who has spent more than a decade writing about space online, wanted to go deep on some of these bots. But she also wanted something more: the stories of the humans that made those missions reality in the first place, and a behind-curtain look at what goes on inside NASA’s walls before the launches, before the press releases, and after NASA-TV stops streaming. And so she spent months traveling to different NASA centers around the country, interviewing 37 scientists and engineers about nine missions: New Horizons, the Hubble Space Telescope, Dawn, Kepler, the Cassini-Huygens probe, the Solar Dynamics Observatory, and the Mars and Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiters.

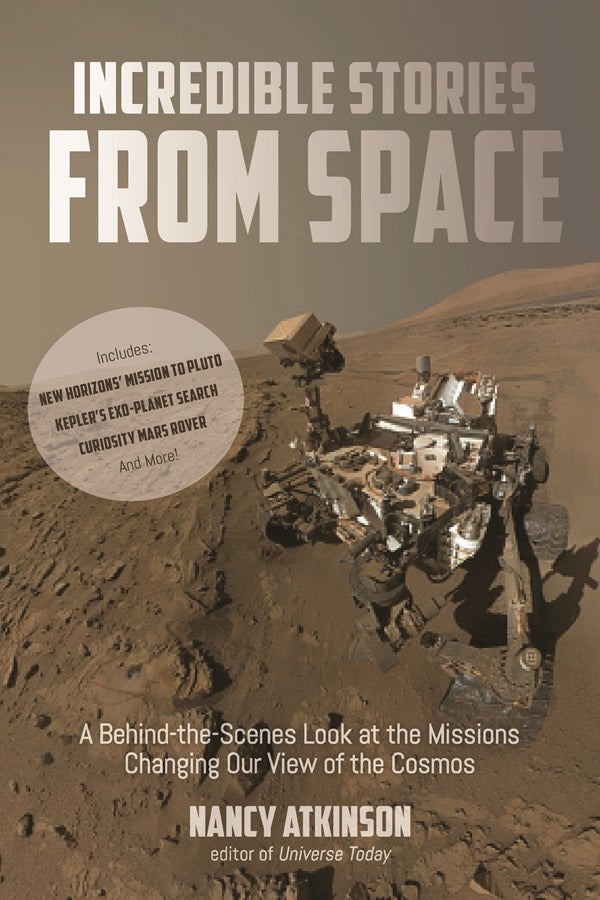

The result of her research is a book called Incredible Stories from Space (Page Street Publishing, 2016). Through the eyes, voices, offices, hardships, and triumphs of some of each mission’s key characters, Atkinson tells the stories you haven’t heard about the solar system’s most famous robotic spacecraft. You’re used to getting the “what,” “when,” and “where” in NASA news. But this book adds “how” and “who,” along with “why [does anyone undertake such ponderous projects on purpose],” from the mouths of the scientists as well as Atkinson herself.

Atkinson is a contributing editor at Universe Today. Here’s what she has to say for herself.

How did you first become interested in space exploration?

I was very young when the Apollo missions were happening, and that was my initial hook into space exploration. I watched them with my sister, and we just sat on the floor glued to the television set. They were my introduction to space exploration, and then came the Voyager missions.

And how did you go from that initial interest to writing about space?

When I worked at the Science Museum of Minnesota, we had access to a one-third actual size inflatable space station. We set it up in the gyms in schools, and often, parents would come. They would say, “That was so awesome! I didn’t even know we had a space station.” It made me realize how little people knew about what was going on in space exploration and made me want to expand my reach.

You’ve now been writing space news for more than a decade. A book is a big departure from the daily science beat. What was your favorite part of this very different reporting process?

Being able to interview most of these people — 37 scientists and engineers — face-to-face was really compelling because as they’re telling you these behind-the-scenes things or the things that aren’t shown on NASA TV, you get to see the emotion on their faces. You just get a better feel for what their work means to them and how excited they are — how passionate and sometimes emotional — about what they do.

I got to go to the Mars Yard [the simulated martian landscape where engineers test robots]. I stood in the control room where the Curiosity rover entry-descent-landing team was when Curiosity arrived on Mars. My guide turned on the Seven Minutes of Terror trailer [which dramatizes the 420 seconds between when the rover hits at the top of the Red Planet’s atmosphere and arrives at its surface]. And I visited Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Lab six months after the New Horizons spacecraft flew by Pluto. I’d seen that room on NASA TV that day, full of people, but here I was in person.

What was the most triumphant moment the scientists told you about?

The night before the New Horizons scientists released that iconic image of Pluto’s “heart,” they were just sleep deprived. Hal Weaver was trying to get the image out and ready for the morning, for its reveal to the world. I hate to call it a comedy of errors, but … (the full details are on page 25 of the book.)

And then there’s the landing of Curiosity. Landing on Mars is so hard! I loved talking to the people who were part of that and getting their emotions. Ashwin Vasavada, the mission’s project scientist, told tell me he was physically sitting in chair but mentally curled up in the fetal position.

What were the most memorable challenges the scientists faced in getting missions to work in space successfully?

The Hubble Space Telescope is just all the challenges and obstacles — from funding issues to political issues to the mirror problem to the space shuttle accident. It really speaks to the persistence and inventiveness and collaboration required for these missions to take place and be so successful. I was really struck by how many missions are international missions even though they’re NASA missions in name. I think that’s really relevant right now: NASA is working across borders, across languages, across so many things to make these missions successful and to accomplish the great things that space exploration entails.

The Dawn mission has also overcome a lot: Two of their reaction wheels, which orient the spacecraft, have failed and the engineers have figured out how to make the mission work with just the two remaining reaction wheels. And when they were just about to go into orbit around the dwarf planet Ceres, a cosmic ray hit. They had to shut down the engines and revamp their approach. By-the-seat-of-your-pants engineering that has really made this mission so successful and enduring.

Mark Rayman, Dawn’s chief engineer, was talking to me about the existential part of space exploration and how it’s part of our DNA to explore. He feels like anybody who’s ever wanted to go to the next horizon or ever wanted to even the next hill is part of this mission. He had me choked up in his office. And he said, “Oh the fact that you’re choked up is just right. That’s exactly what I’m talking about.”

What, personally, is your favorite mission?

As far as the ones I deal with in the book, that has to be the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. I spoke with the people behind the scenes that most people would never hear about — like Christian Schaller, Kristin Block, and Sarah Milkovich, who worked on the HiRISE camera, and Neil Mottinger, who has helped navigate the spacecraft. I got their insight in what it’s like to run the nuts and bolts of a mission, the parts of it that the majority of people don’t hear about. They are emotionally attached to what they do, and excited to find, say, something they were looking for in the images, or to have a particular software routine work.

Are there trends you noticed that were common between all the missions?

None of these missions — with the exception of the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter — came easy. Alan Stern of New Horizons was pushing for 10 years for NASA to choose that mission. Other spacecraft had the same problem. They almost all had challenges getting chosen, then put together, and then launched. Mostly I think I just came to appreciate everyone’s passion and enthusiasm for what they do.

They know that what they do isn’t like the Apollo missions, where everything they do is being broadcast on television nonstop. They’re working in anonymity and obscurity sometimes. But they wanted to share the inside stories of what they do — for one, because they’re on the taxpayer dime, and two, because not a lot of people get to have jobs like theirs.