Seeing nothing can be a significant observation. It may even be the key to a celestial puzzle.

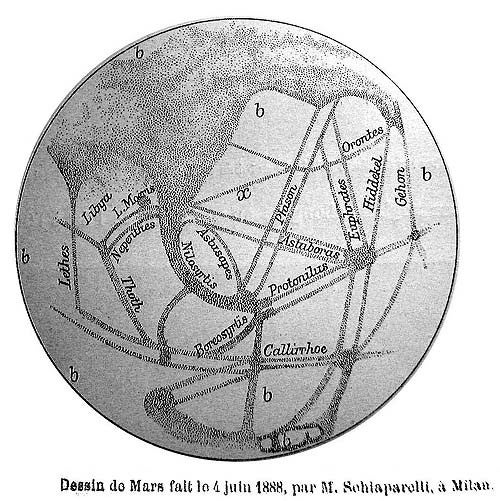

The most famous example is the martian canals. When Giovanni Schiaparelli observed a supersized, 25-arcsecond Mars during its 1877 opposition, he saw dark lines he thought were river channels, or canali. After the word was mistranslated as “canals” and noted astronomers like Percival Lowell mistakenly confirmed their existence, the public went nuts. Artificial structures must mean intelligent life! The idea gained traction after Lowell wrote the 1906 book Mars and Its Canals.

So, a century ago, when several largest-ever telescopes were completed, the world eagerly read the blockbuster news: no canals. They weren’t there. Yet the story didn’t end. The May 1938 issue of Popular Astronomy has a British astronomer’s drawing of the 1937 Mars opposition, complete with distinct canals and a note saying they were “quite definite.” The media knew where public excitement lay, and it wasn’t in the reports of “seeing nothing.”

That’s why, when I visit a school and telescopically show the Sun using a full aperture filter, narration is easy when there are lots of sunspots. But sometimes the Sun is blank; the mission then becomes how to make a featureless surface fascinating. How can blankness be cool?

The solution: I explain solar storms and what they mean, and what the lack of any spots means. So, what is the Sun doing today? The kids in line excitedly squirm with curiosity and anticipation. Then each takes a look and discovers the result. To them, seeing “nothing” is now a meaningful observation, and a powerful one.

My very first it’s-not-there experience came from a Patrick Moore book that I read as a teenager. Listing double stars, it said Antares has a green companion. And it did appear green at the eyepiece. But the book also listed Beta (β) Librae as green, and that star merely looked white.

Soon, studying college astrophysics, I realized why there are no green stars. It’s because green occupies the middle of the spectrum. For it to visually dominate, both the red and blue ends would have to be suppressed, which can’t happen. (Yellow’s in the middle of the spectrum, too, but that color is created by the mixture of green and red light, which can easily combine because their ranges slightly overlap.)

But you can’t get green from any mixture of colored light. Those books that listed green stars were simply wrong. As for the companion to Antares, the solution is nowadays widely known. After looking at the distinctly reddish glow of the bright primary, the human eye projects a green afterimage onto any nearby white surface.

Halos around streetlights can be another reality probe. They appear in certain atmospheric conditions. Or you may see equally vivid rings if your eyes are irritated after swimming in a pool. Are the rings really there? Just block out the streetlight with an outstretched fingertip. If the halo persists, everyone is seeing it. If it abruptly vanishes, it’s not real, but manufactured by your eye.

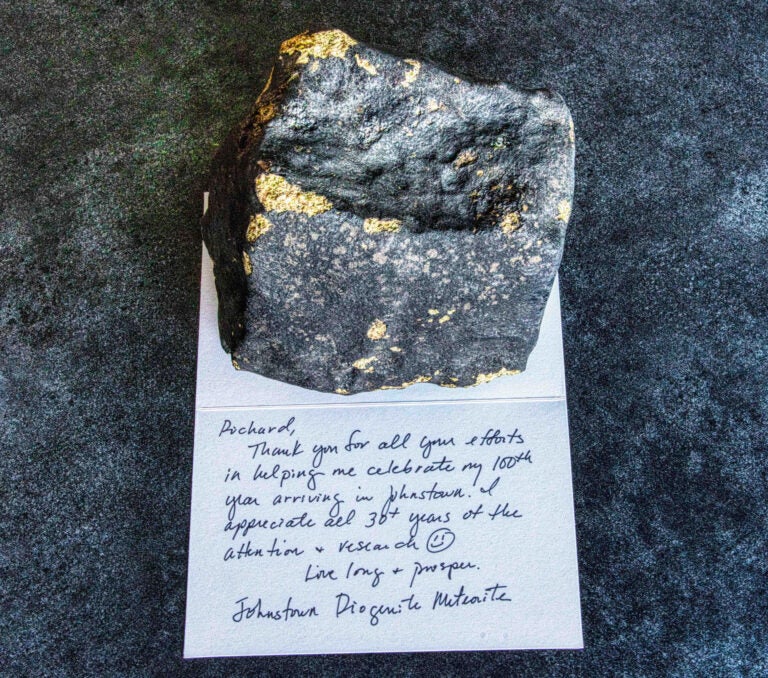

Scientists need to be very careful about seemingly null results. The 1976 Viking landers looked for martian life by adding soil to a damp, nutrient-rich, radiation-tagged substance, and later analyzing the resulting gases. On Earth, life alters its surrounding air, like when we exhale CO2. If there were life in the martian soil, researchers assumed, it would metabolize the nutrients and give off gases containing the radioactive tracer. Sure enough, the air in the lander’s chamber became radioactive. Then the lander sterilized a second sample to destroy any microorganisms. In the subsequent test, the air didn’t change.

Ultimately, NASA said the tests were negative: no life. They decided the results came from some strange, unknown chemistry. But to this day, many others — including the experiment’s designer and principal investigator, Gilbert Levin — insist we found life on Mars back in 1976. (Intrigued? Dig deeper by googling “labeled release experiment.”)

Martian canals, green stars, and certain halos are good introductory hallucinations. Send us others and we’ll dive even deeper into our noble ongoing quest: to make much ado about nothing.