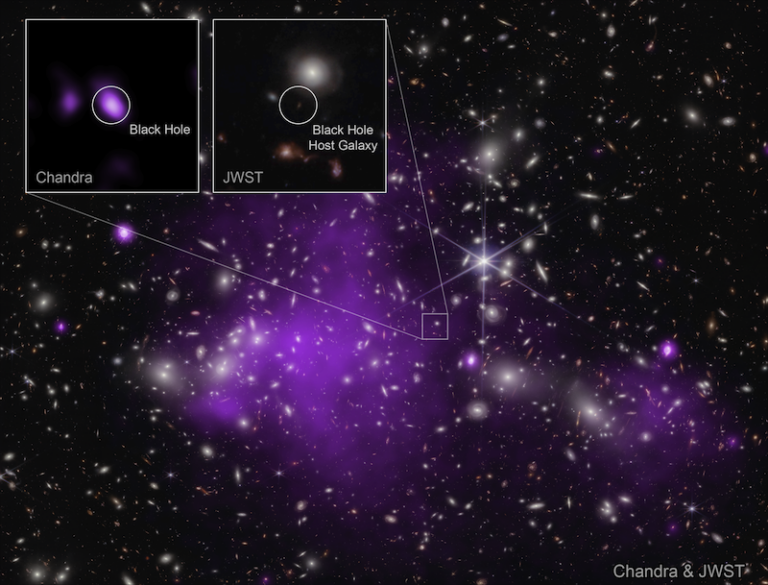

The finding suggests that quasars — the brilliant cores of active galaxies — may commonly host two central supermassive black holes that fall into orbit about one another as a result of the merger between two galaxies. Like a pair of whirling skaters, the black hole duo generates tremendous amounts of energy that makes the core of the host galaxy outshine the glow of the galaxy’s population of billions of stars, which scientists then identify as quasars.

Scientists looked at Hubble archival observations of ultraviolet radiation emitted from the center of Mrk 231 to discover what they describe as “extreme and surprising properties.”

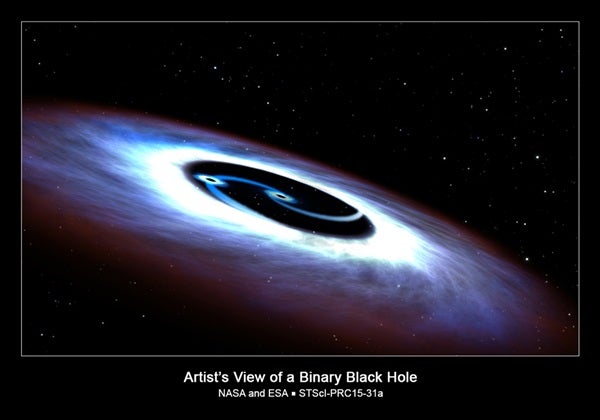

If only one black hole were present in the center of the quasar, the whole accretion disk made of surrounding hot gas would glow in ultraviolet rays. Instead, the ultraviolet glow of the dusty disk abruptly drops off toward the center. This provides observational evidence that the disk has a big doughnut hole encircling the central black hole. The best explanation for the observational data, based on dynamical models, is that the center of the disk is carved out by the action of two black holes orbiting each other. The second smaller black hole orbits in the inner edge of the accretion disk and has its own mini-disk with an ultraviolet glow.

“We are extremely excited about this finding because it not only shows the existence of a close binary black hole in Mrk 231 but also paves a new way to systematically search binary black holes via the nature of their ultraviolet light emission,” said Youjun Lu of the National Astronomical Observatories of China, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

“The structure of our universe, such as those giant galaxies and clusters of galaxies, grows by merging smaller systems into larger ones, and binary black holes are natural consequences of these mergers of galaxies,” said Xinyu Dai of the University of Oklahoma.

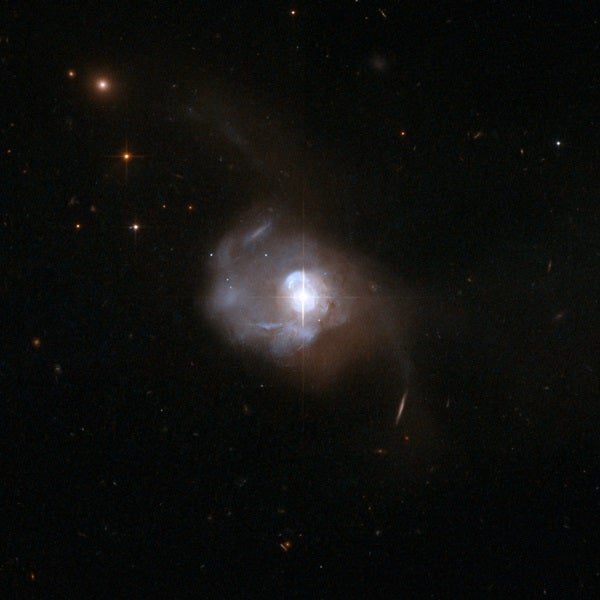

The lower-mass black hole is the remnant of a smaller galaxy that merged with Mrk 231. Evidence of a recent merger comes from the host galaxy’s asymmetry and the long tidal tails of young blue stars.

The result of the merger has been to make Mrk 231 an energetic starburst galaxy with a star formation rate 100 times greater than that of our Milky Way Galaxy. The infalling gas fuels the black hole “engine,” triggering outflows and gas turbulence that incites a firestorm of star birth.

The binary black holes are predicted to spiral together and collide within a few hundred thousand years.

Mrk 231 is located 600 million light-years away.