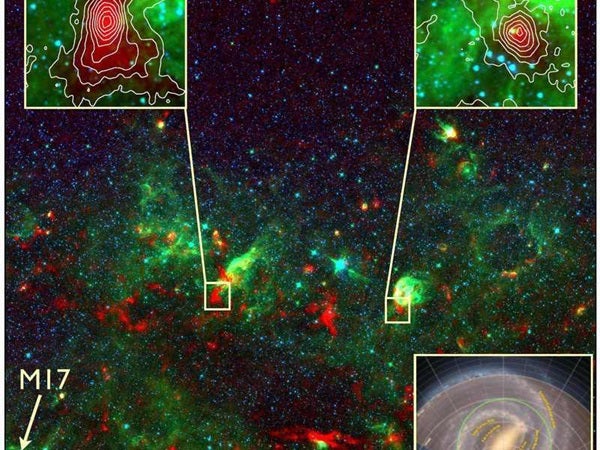

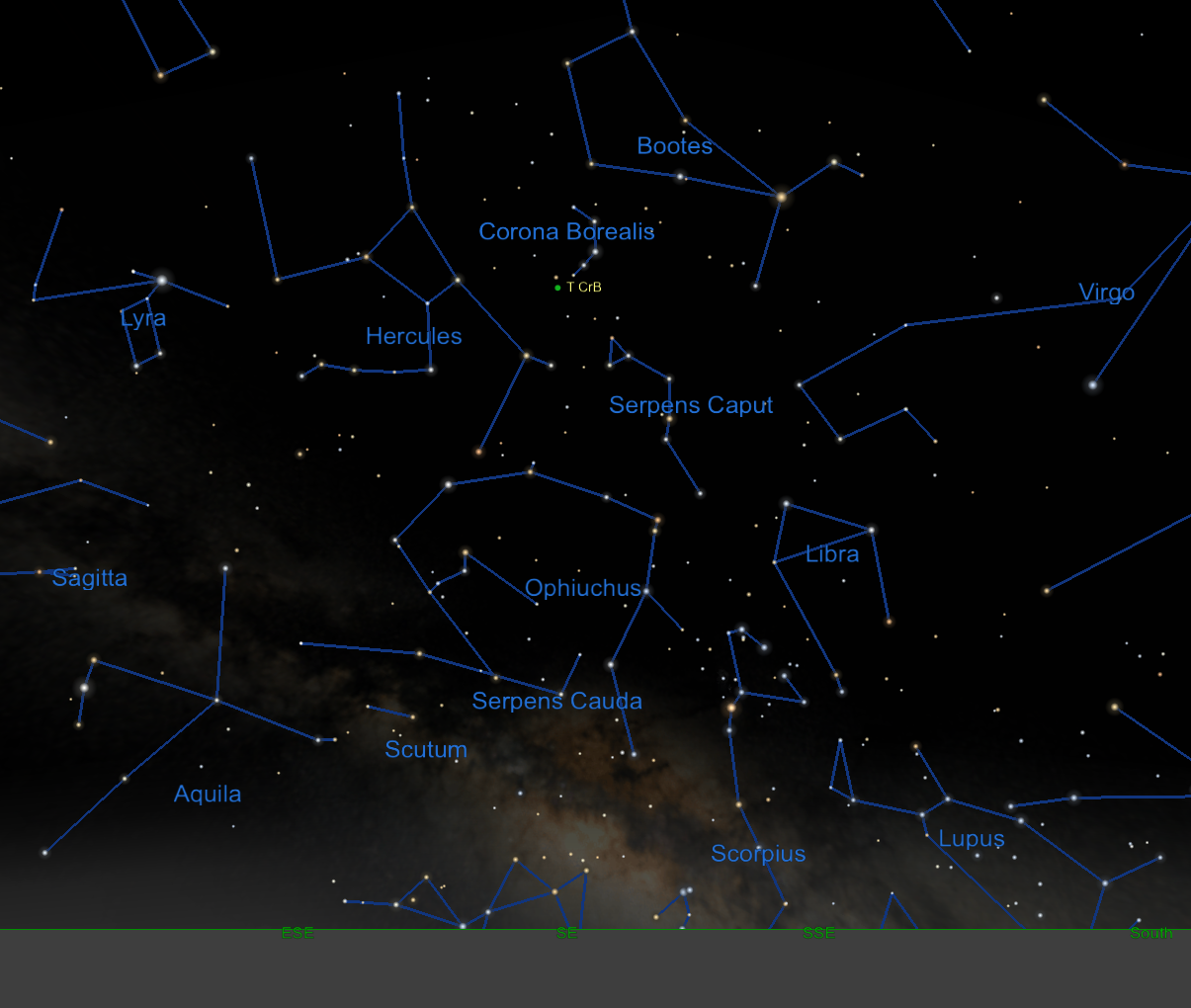

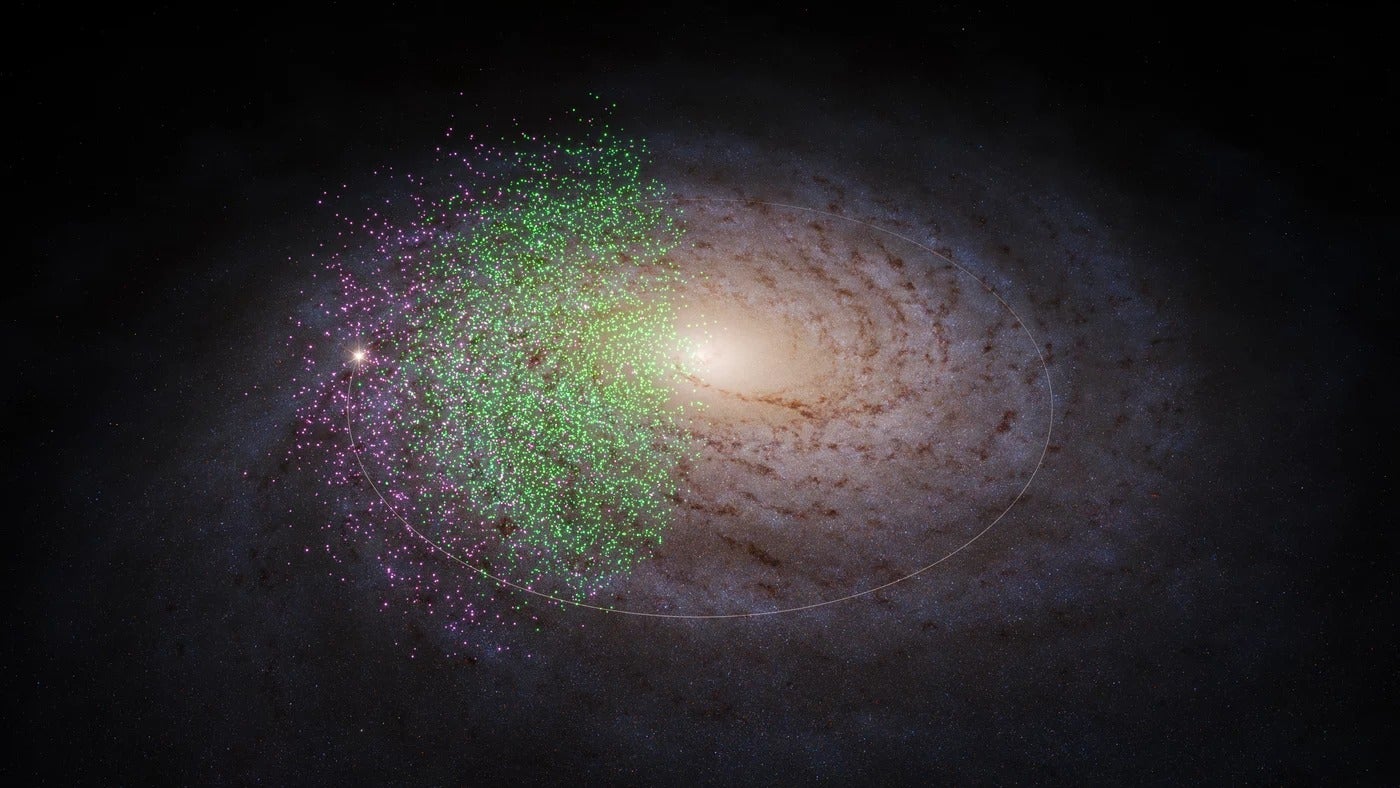

An international team of astronomers used the APEX telescope with its submillimeter camera, LABOCA, built at the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy (MPIfR), to survey the inner galaxy to search for the birthplaces of the most massive stars currently forming in the Milky Way. The APEX telescope is located on the Chajnantor Plateau in Chile at 16,700-feet (5,100 meters) altitude, which is one of the few places on Earth where observations at submillimeter wavelengths are possible. The APEX Telescope Large Area Survey of the Galaxy (ATLASGAL) covers more than 420 square degrees of the galactic plane, which corresponds to 97 percent of the inner galaxy within the solar circle. Thus, it includes large sections of all four spiral arms and approximately two-thirds of the entire molecular disk of the Milky Way. This data set therefore includes the majority of all massive star-forming nurseries in the galaxy and is being used to construct a 3-D map of the Milky Way.

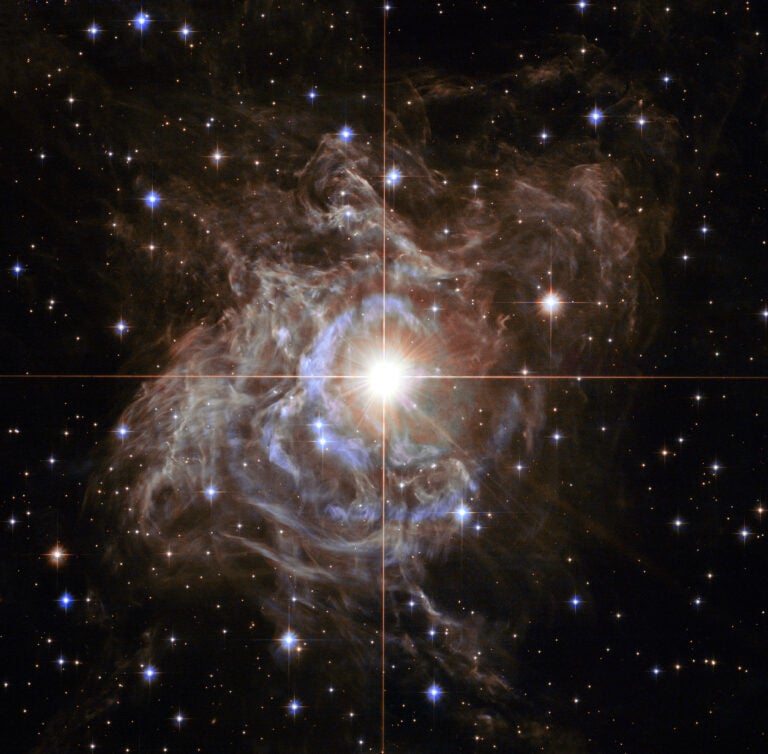

ATLASGAL provides an unprecedented census of the cold and dense environments where the most massive stars in our galaxy begin their lives. The material in these stellar nurseries is so dense that optical and infrared light emitted from the embedded young high-mass stars cannot escape. Therefore, the earliest stages of star formation are effectively hidden at these short wavelengths, and longer wavelengths are required to probe these regions. The ATLASGAL survey detects emission at submillimeter wavelengths, which is dominated by emission from cold dust. It provides a detailed view of the birthplaces where the next generation of massive stars is being formed.

As these dusty corners of our galaxy are difficult to access, such surveys provide the large-scale coverage to search for the stellar nurseries forming the most massive stars in our galaxy. “Our team has now analyzed this survey, revealing the largest sample of the so-far hidden places of massive star formation,” said Timea Csengeri from MPIfR. “We have identified many new potential sites where the most massive stars currently form in our galaxy.”

Providing unprecedented statistics, scientists reveal that the processes to build up the cold dense sites where the most massive stars in our galaxy form occur rapidly, taking place within only 75,000 years, which is much shorter than the corresponding timescales in nurseries of lower-mass stars like our Sun. This is the first global indication that star formation is a fast process in our galaxy.

“We characterized these places to search for signatures revealing how massive stars form within them,” said James Urquhart, also from MPIfR. “The fast and furious life of the most massive stars was already known. And now we could also show that it is initiated by a pretty short infancy within their stellar cocoons.” The lifetime of massive stars is about 1,000 times shorter than the lifetime of stars like the Sun, and the new results reveal that they also form on short timescales and in a much more dynamic star formation process.

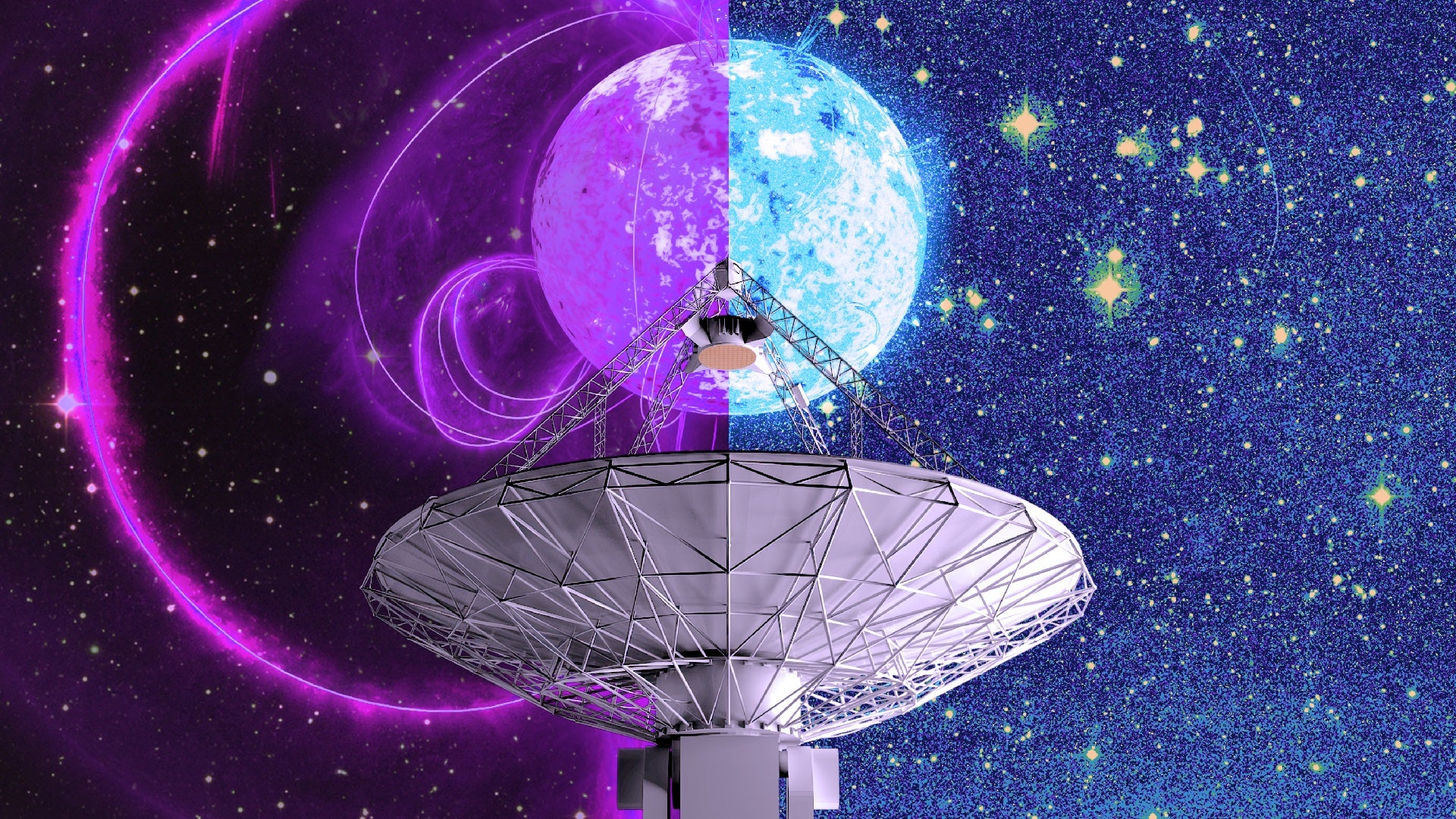

“Only telescopes at exceptional locations, such as the high and dry Chajnantor Plateau in Chile, are capable to observe in this frequency range,” said Frederic Schuller from the European Southern Observatory. “This is the largest area in the sky surveyed from a ground-based telescope in the submillimeter wavelength regime.”

“ATLASGAL also provides a ‘finding chart’ for the most extreme dust cocoons, where the innermost processes of stellar birth can be studied at much higher angular resolution with the new ALMA interferometer, located just next to the APEX telescope,” said Friedrich Wyrowski, from MPIfR.