Key Takeaways:

“This discovery illustrates the power of tackling a problem in astronomy with different wavelengths of light,” said Paul Goldsmith from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “Herschel’s eye for longer-wavelength infrared light has given us new tools for addressing a profound cosmic mystery.”

Cosmic dust is made of various elements, such as carbon, oxygen, iron, and other atoms heavier than hydrogen and helium. It is the stuff of which planets and people are made, and it is essential for star formation. Stars like our Sun churn out flecks of dust as they age, spawning new generations of stars and their orbiting planets.

Astronomers have for decades wondered how dust was made in our early universe. Back then, Sun-like stars had not been around long enough to produce the enormous amounts of dust observed in distant, early galaxies. Supernovae, on the other hand, are the explosions of massive stars that do not live long.

The new Herschel observations are the best evidence yet those supernovae are, in fact, the dust-making machines of the early cosmos.

“The Earth on which we stand is made almost entirely of material created inside a star,” said Margaret Meixner from the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland. “Now we have a direct measurement of how supernovae enrich space with the elements that condense into the dust that is needed for stars, planets, and life.”

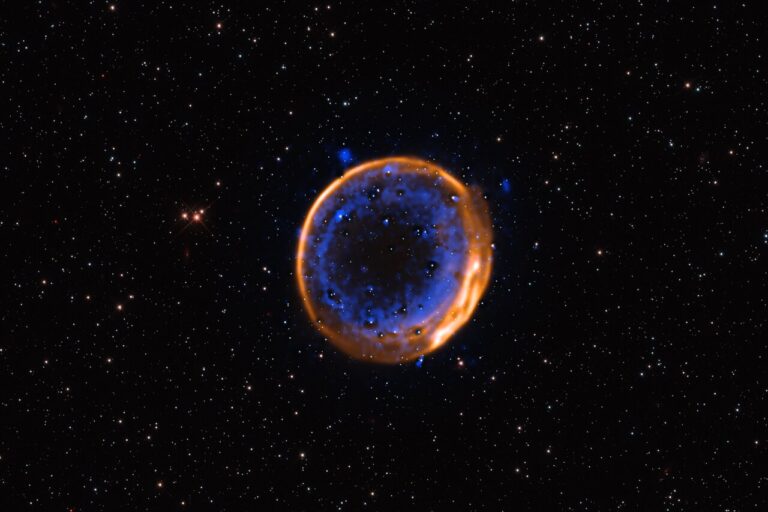

The study focused on the remains of the most recent supernova to be witnessed with the naked eye from Earth. Called SN 1987A, this remnant is the result of a stellar blast that occurred 170,000 light-years away and was seen on Earth in 1987. As the star blew up, it brightened in the night sky and then slowly faded over the following months. Because astronomers are able to witness the phases of this star’s death over time, SN 1987A is one of the most extensively studied objects in the sky.

Initially, astronomers weren’t sure if the Herschel telescope could even see this supernova remnant. Herschel detects the longest infrared wavelengths, which means it can see cold objects that emit little heat, such as dust. But it so happened that SN 1987A was imaged during a Herschel survey of the object’s host galaxy — a small neighboring galaxy called the Large Magellanic Cloud.

After the scientists retrieved the images from space, they were surprised to see that SN 1987A was aglow with light. Careful calculations revealed that the glow was coming from enormous clouds of dust, consisting of 10,000 times more material than previous estimates. The dust is about –429° to –416° Fahrenheit (–256° to –249° Celsius) — colder than Pluto, which is about –400° Fahrenheit (204° Celsius).

“Our Herschel discovery of dust in SN 1987A can make a significant understanding in the dust in the Large Magellanic Cloud,” said Mikako Matsuura from University College London in England. “In addition to the puzzle of how dust is made in the early universe, these results give us new clues to mysteries about how the Large Magellanic Cloud and even our own Milky Way became so dusty.”

Previous studies had turned up some evidence that supernovae are capable of producing dust. For example, NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope, which detects shorter infrared wavelengths than Herschel, found 10,000 Earth masses worth of fresh dust around the supernova remnant called Cassiopeia A. Hershel could see even colder material, and thus the coldest reservoirs of dust. “The discovery of up to 230,000 Earths worth of dust around SN 1987A is the best evidence yet that these monstrous blasts are, indeed, mighty dust makers,” said Eli Dwek, from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

“This discovery illustrates the power of tackling a problem in astronomy with different wavelengths of light,” said Paul Goldsmith from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “Herschel’s eye for longer-wavelength infrared light has given us new tools for addressing a profound cosmic mystery.”

Cosmic dust is made of various elements, such as carbon, oxygen, iron, and other atoms heavier than hydrogen and helium. It is the stuff of which planets and people are made, and it is essential for star formation. Stars like our Sun churn out flecks of dust as they age, spawning new generations of stars and their orbiting planets.

Astronomers have for decades wondered how dust was made in our early universe. Back then, Sun-like stars had not been around long enough to produce the enormous amounts of dust observed in distant, early galaxies. Supernovae, on the other hand, are the explosions of massive stars that do not live long.

The new Herschel observations are the best evidence yet those supernovae are, in fact, the dust-making machines of the early cosmos.

“The Earth on which we stand is made almost entirely of material created inside a star,” said Margaret Meixner from the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland. “Now we have a direct measurement of how supernovae enrich space with the elements that condense into the dust that is needed for stars, planets, and life.”

The study focused on the remains of the most recent supernova to be witnessed with the naked eye from Earth. Called SN 1987A, this remnant is the result of a stellar blast that occurred 170,000 light-years away and was seen on Earth in 1987. As the star blew up, it brightened in the night sky and then slowly faded over the following months. Because astronomers are able to witness the phases of this star’s death over time, SN 1987A is one of the most extensively studied objects in the sky.

Initially, astronomers weren’t sure if the Herschel telescope could even see this supernova remnant. Herschel detects the longest infrared wavelengths, which means it can see cold objects that emit little heat, such as dust. But it so happened that SN 1987A was imaged during a Herschel survey of the object’s host galaxy — a small neighboring galaxy called the Large Magellanic Cloud.

After the scientists retrieved the images from space, they were surprised to see that SN 1987A was aglow with light. Careful calculations revealed that the glow was coming from enormous clouds of dust, consisting of 10,000 times more material than previous estimates. The dust is about –429° to –416° Fahrenheit (–256° to –249° Celsius) — colder than Pluto, which is about –400° Fahrenheit (204° Celsius).

“Our Herschel discovery of dust in SN 1987A can make a significant understanding in the dust in the Large Magellanic Cloud,” said Mikako Matsuura from University College London in England. “In addition to the puzzle of how dust is made in the early universe, these results give us new clues to mysteries about how the Large Magellanic Cloud and even our own Milky Way became so dusty.”

Previous studies had turned up some evidence that supernovae are capable of producing dust. For example, NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope, which detects shorter infrared wavelengths than Herschel, found 10,000 Earth masses worth of fresh dust around the supernova remnant called Cassiopeia A. Hershel could see even colder material, and thus the coldest reservoirs of dust. “The discovery of up to 230,000 Earths worth of dust around SN 1987A is the best evidence yet that these monstrous blasts are, indeed, mighty dust makers,” said Eli Dwek, from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.