A stronomers who used powerful telescopes in Arizona and Chile in a survey for planets around nearby stars have discovered extrasolar planets more massive than Jupiter are extremely rare in other outer solar systems.

University of Arizona astronomers and their collaborators from the European Southern Observatory, Max Planck Institute for Astronomy at Heidelberg, Italy’s Arcetri Observatory, the W.M. Keck Observatory and the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics just concluded a benchmark 3-year survey using direct-detection techniques sensitive to planets farther from their stars. The survey looked at 54 young, nearby stars that were among the best candidates for having detectable giant Jupiter-like planets at distances beyond 5 astronomical units (AU), or the distance between Jupiter and the sun. (One AU is the distance between Earth and the sun.)

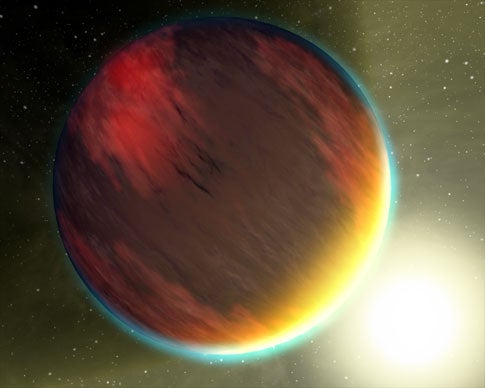

Since 1995, astronomers have found more than 230 “super Jupiters” orbiting very close to their parent stars using the radial velocity method. This indirect planet-detecting technique measures the slight back-and-forth motion of the star as it is tugged by an unseen planet’s gravity. Scientists have written more than 2,000 scholarly papers about these giant Jupiter-like planets within a few Earth-to-sun distances of their stars.

However, the radial velocity method presently used is most sensitive to planets close to their stars. The technique reveals little about extrasolar planets farther out in nearby solar systems.

Astronomers need other techniques to map extrasolar planets beyond 5 AU so they can determine what the “average” planetary system looks like — and whether ours is a typical solar system.

The 3-year survey didn’t turn up even one giant extrasolar planet in the outer part of any nearby solar system.

“We certainly had the ability to detect outer super Jupiter planets at 10 AU, and farther out, around young sun-like stars,” said UA astronomy Professor Laird Close. Close, along with Rainer Lenzen of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, Heidelberg, and Don McCarthy of the University of Arizona, designed the unique, methane-planet sensitive imagers used on two powerful telescopes for the survey.

“The odds are extremely slight that planets larger than four to five Jupiter masses exist at distances greater than 20 AU from these stars,” concluded graduating doctoral student Beth Biller of the UA Steward Observatory. Biller is lead author on the first scholarly paper reporting direct-imaging results for farther-out massive Jupiters from this survey, the most sensitive to date.

“There is no ‘planet oasis’ between 20 and 100 AU,” doctoral student Eric Nielsen of UA’s Steward Observatory agreed. “We achieved contrasts high enough to find these super Jupiters, but didn’t.” 20 AU is the orbital distance of the planet Uranus in our own solar system.

Astronomers were surprised in the early days of planet finding to discover a population of planets more massive than Jupiter, within the orbit of Mercury, taking only a few days to orbit their host star, Biller said. “Now that we know there aren’t large numbers of giant planets lurking at large distances from their stars, astronomers have a more complete picture, and can better constrain how planets are formed,” she said.