Key Takeaways:

We have just published evidence in Nature Astronomy for what might be producing mysterious bursts of radio waves coming from distant galaxies, known as fast radio bursts or FRBs.

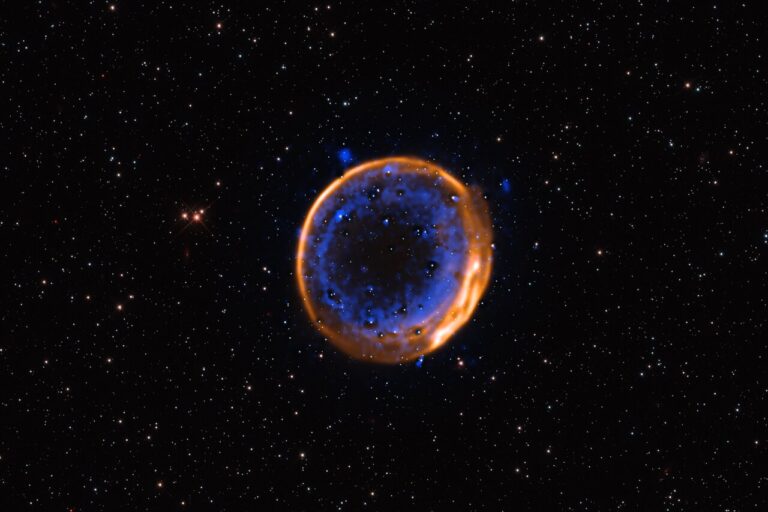

Two colliding neutron stars — each the super-dense core of an exploded star — produced a burst of gravitational waves when they merged into a “supramassive” neutron star. We found that two and a half hours later they produced an FRB when the neutron star collapsed into a black hole.

Or so we think. The key piece of evidence that would confirm or refute our theory — an optical or gamma-ray flash coming from the direction of the fast radio burst — vanished almost four years ago. In a few months, we might get another chance to find out if we are correct.

Brief and powerful

FRBs are incredibly powerful pulses of radio waves from space lasting about a thousandth of a second. Using data from a radio telescope in Australia, the Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder (ASKAP), astronomers have found that most FRBs come from galaxies so distant, light takes billions of years to reach us. But what produces these radio wave bursts has been puzzling astronomers since an initial detection in 2007.

The best clue comes from an object in our galaxy known as SGR 1935+2154. It’s a magnetar, which is a neutron star with magnetic fields about a trillion times stronger than a fridge magnet. On April 28, 2020, it produced a violent burst of radio waves — similar to an FRB, although less powerful.

Astronomers have long predicted that two neutron stars — a binary — merging to produce a black hole should also produce a burst of radio waves. The two neutron stars will be highly magnetic, and black holes cannot have magnetic fields. The idea is the sudden vanishing of magnetic fields when the neutron stars merge and collapse to a black hole produces a fast radio burst. Changing magnetic fields produce electric fields — it’s how most power stations produce electricity. And the huge change in magnetic fields at the time of collapse could produce the intense electromagnetic fields of an FRB.

The search for the smoking gun

To test this idea, Alexandra Moroianu, a masters student at the University of Western Australia, looked for merging neutron stars detected by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) in the U.S. The gravitational waves LIGO searches for are ripples in space-time, produced by the collisions of two massive objects, such as neutron stars.

LIGO has found two binary neutron star mergers. Crucially, the second, known as GW190425, occurred when a new FRB-hunting telescope called CHIME was also operational. However, being new, it took CHIME two years to release its first batch of data. When it did so, Moroianu quickly identified a fast radio burst called FRB 20190425A which occurred only two and a half hours after GW190425.

Exciting as this was, there was a problem – only one of LIGO’s two detectors was working at the time, making it very uncertain where exactly GW190425 had come from. In fact, there was a 5 percent chance this could just be a coincidence.

Worse, the Fermi satellite, which could have detected gamma rays from the merger — the “smoking gun” confirming the origin of GW190425 — was blocked by Earth at the time.

Unlikely to be a coincidence

However, the critical clue was that FRBs trace the total amount of gas they have passed through. We know this because high-frequency radio waves travel faster through the gas than low-frequency waves, so the time difference between them tells us the amount of gas.

Because we know the average gas density of the universe, we can relate this gas content to distance, which is known as the Macquart relation. And the distance travelled by FRB 20190425A was a near-perfect match for the distance to GW190425. Bingo!

So have we discovered the source of all FRBs? No. There are not enough merging neutron stars in the Universe to explain the number of FRBs — some must still come from magnetars, like SGR 1935+2154 did.

And even with all the evidence, there’s still a one in 200 chance this could all be a giant coincidence. However, LIGO and two other gravitational wave detectors, Virgo, and KAGRA, will turn back on in May this year, and be more sensitive than ever, while CHIME and other radio telescopes are ready to immediately detect any FRBs from neutron star mergers.

In a few months, we may find out if we’ve made a key breakthrough — or if it was just a flash in the pan.

Clancy W. James would like to acknowledge Alexandra Moroianu, the lead author of the study; his co-authors, Linqing Wen, Fiona Panther, Manoj Kovalem (University of Western Australia), Bing Zhang and Shunke Ai (University of Nevada); and his late mentor, Jean-Pierre Macquart, who experimentally verified the gas-distance relation, which is now named after him.

Clancy William James, Senior Lecturer (astronomy and astroparticle physics), Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.