Key Takeaways:

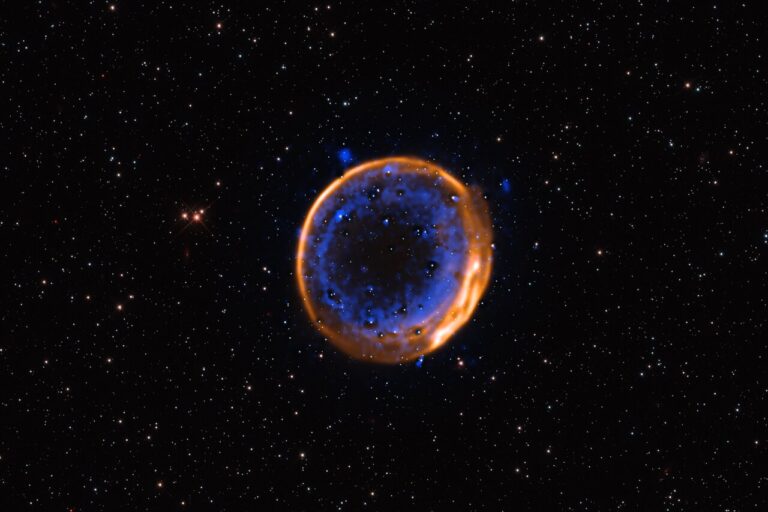

infrared images) highlights color differences in the moon’s water-ice crust. Dark brown areas represent rocky material, bright bluish plains in the polar areas are possibly

coarse-grained ice (dark blue) and fine-grained ice (light blue). Long, dark lines are fractures in the crust, some of which are more than 1,850 miles (3,000 kilometers) long.

The Europa Focus Group, a group of scientists and engineers organized through Arizona State University and supported by NASA, held its fifth annual meeting in February in Mountain View, California, to discuss strategies for exploring that moon of Jupiter. Europa’s ice crust seems to cover a liquid-water ocean up to 60 miles (100 kilometers) thick, which may have served as a site for microscopic life to evolve — and to live in to this day. While NASA’s recent budget cuts have postponed missions to Europa, researchers continue to plan missions and consider the exciting possibility of life there.

Last year, Congress provided the first tentative funding to develop Europa Orbiter — the mission generally regarded as the next step in exploring Europa. Unfortunately, Europa Orbiter is a complex and expensive mission — as much as $1.5 billion. No sooner had the initial funding been set than the still-rising demands of NASA’s manned space programs forced large cuts in space-science spending. Europa Orbiter was one victim, and one purpose of this meeting was to design possible ways to recover.

The general conclusion was that Europa specialists should join the larger space-science community in demanding a restoration of part of the budget cuts, either by raising NASA’s total budget or by transferring some funds back from the manned program.

The main purpose of the Europa Focus Group, however, has always been to define the next steps for the scientific exploration of Europa. The latest design for Europa Orbiter is far more capable than before — a new plan calls for the craft to reach Jupiter by making two Earth flybys and one Venus flyby to catapult itself out to Jupiter’s orbit, instead of being launched there directly. This move triples the mass that can be put into orbit around Europa and has already allowed the spacecraft’s payload of science instruments to be quintupled.

The design allows the spacecraft to carry yet another 750 pounds into Europa orbit without increasing the size of the launcher. Some of this weight could be used to raise the science payload still further, or to provide more radiation shielding to prolong the life of the spacecraft’s electronics in the savage environment of Jupiter’s inner radiation belts.

There’s also the possibility of adding a small piggyback lander to Europa Orbiter to make initial surface studies in preparation for later much larger “astrobiology landers.” Such landers would collect ice samples from the near subsurface and analyze them for any frozen germs that might have been carried up from the ocean with other dissolved materials and left embedded in the ice. The main purpose of an initial small piggyback lander would likely be to get engineering data on the roughness and makeup of Europa’s icy surface, to ensure that later landers could survive their landings and obtain good samples.

Another purpose of the meeting was for scientists to present their latest conclusions about Europa. Most of them were detailed reinterpretations of data acquired by the Galileo spacecraft. But there were two big revelations. First, William McKinnon of Washington University said the most detailed analysis yet of Galileo’s magnetic-field measurements near Europa has now proven beyond doubt that the moon has a relatively thin layer near its surface that is so electrically conductive that the only plausible composition is seawater with a large amount of dissolved sulfate salts.

Second, John Spencer of the Southwest Research Institute used Hawaii’s Keck Telescope to obtain near-infrared spectra of Europa’s ice with a resolution 18 times better than Galileo’s spectrometer. To his disappointment, the new spectra show no substances not present in Galileo’s coarser spectra. But the new spectra do provide strong evidence that the main substances mixed with the water ice are, indeed, sulfates of magnesium and sodium, along with a considerable amount of sulfuric acid — a conclusion agreed with by two other researchers at the meeting.

Europa’s ocean is thus likely to be quite acidic. This doesn’t necessarily make it hostile to microbes, but there is some debate over whether complex organic compounds could evolve into life in this environment. On Earth, it appears to have happened in non-acid water, with some bacteria later evolving into highly specialized acid-tolerating forms. Nonetheless, Europa remains on the short list of solar system places that might harbor life.