First new shuttle external tank to ship

In a briefing to reporters December 28, Lockheed Martin Space Systems announced it expects shortly to finish building External Tank 120, which will launch with the first shuttle to return to flight. The tank will leave the company’s plant in New Orleans December 30 and will ship by barge to the Kennedy Space Center in Florida on the 31st. It should arrive at Kennedy by January 6. On arrival, the tank will be tested and mated with the solid rocket boosters and the shuttle orbiter Discovery for launch next May or June.

The tank’s design has been modified to reduce or eliminate the risk of foam insulation or ice falling off at launch and damaging the shuttle. (A briefcase-size piece of foam struck the shuttle Columbia at launch, damaging its left wing and causing the orbiter to break up on reentry, killing the crew.) The Columbia Accident Investigation Board recommended no foam piece weighing more than 0.03 pound should come loose; the tank’s new design should meet or exceed that. Said Ron Wetmore of Lockheed Martin, “This will be the safest, most reliable external tank that we’ve ever delivered.” — Robert Burnham

Touch the Sun without being burned

Educator and author Noreen Grice has brought the wonder of astronomy to visually impaired students with her innovative books, Touch the Universe and Touch the Stars. The books contain images of familiar astronomical objects, but Grice has added texture to the images to communicate colors, shapes, and other intricate details of the cosmos.

Grice’s new book, Touch the Sun (Joseph Henry Press), studies our home star and space weather, enabling visually impaired readers to feel what they cannot see. With Braille and large-print descriptions for each of the book’s 16 photographs, the book is designed for readers of all visual abilities.

The book is scheduled for release in March or April 2005, and approximately 2,500 copies will be printed. Most of these will be given free of charge to visually impaired students, with the assistance of the National Organization of Parents of Blind Children, a division of the National Federation of the Blind. The public may purchase any remaining copies. Joseph Henry Press will print additional volumes based on demand. — Jeremy McGovern

Giant mirror ordered for a giant scope

The University of Arizona Steward Observatory Mirror Laboratory has agreed to cast a 27.5-foot (8.4 meter) mirror for the Giant Magellan Telescope (GMT). The lab hopes to finish this mirror — the first of seven — in summer 2005.

Composed of one mirror surrounded by 6 off-axis mirrors, the scope will have an effective aperture of 83 feet (25.4m). Astronomers will use the GMT to study exoplanets, look back toward the Big Bang, investigate black-hole formation, and tackle dark matter. With this milestone reached, project scientists are giddy about this massive instrument’s potential.

“It [the GMT] will open up incredible new vistas in cosmology, star formation, and the study of stars and planets, to name just a few,” explains John Huchra of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, one of the GMT’s partners. “I started my career observing on a 100-inch telescope. It would be great to work on a 1,000-inch!”

Scheduled for completion in 2016, the GMT will be located at the Carnegie Observatories’ site in Las Campanas, Chile. — Jeremy McGovern

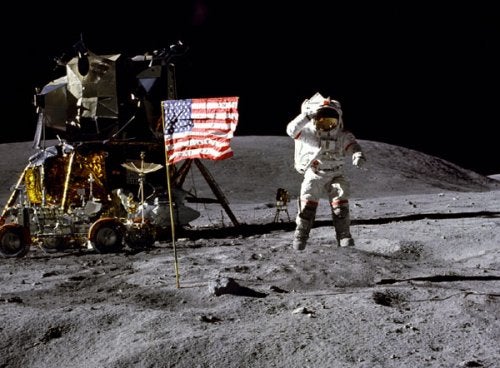

Astronaut John Young retires after 4 decades of service

John Young’s career at NASA has spanned from Gemini to the space shuttle. After over 40 years, the astronaut has retired.

Throughout his NASA career, Young also served in a number of roles at the Johnson Space Center, including associate director.

NASA Administrator Sean O’Keefe commented that Young never sought fame — he cared only about the mission at hand. “John’s tenacity and dedication are matched only by his humility,” says O’Keefe. “However, when you need a job done and you want it done right, John’s the person to go to. He’s a true American treasure, and his exemplary legacy will inspire generations of new explorers for years to come.” — Jeremy McGovern

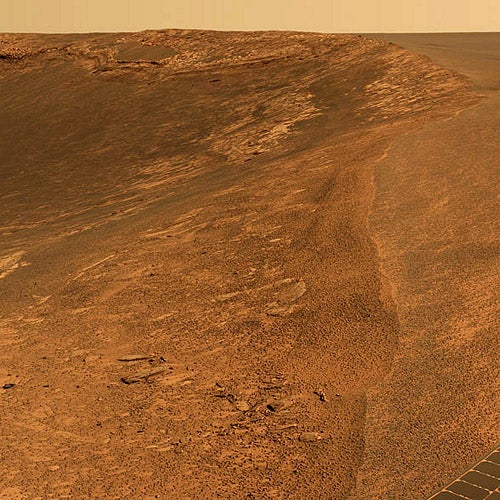

Exactly what processes made martian soil the way we find it today — rich in colorful, and sometimes strongly magnetic, iron oxides and hydroxides — eludes planetary scientists. To shed light on martian soil chemistry, a team led by Vincent Chevrier of the University of Aix-en-Provence in France watched powders of natural and synthetic iron weather for a year under a simulated martian atmosphere.

Chevrier and colleagues exposed powders of synthetic iron and magnetite (an iron oxide, Fe3O4) and natural hexagonal pyrrhotite (an iron sulfide, Fe9S10) for a full year in two atmospheres — water plus carbon dioxide for one set, water plus hydrogen peroxide for the other. To speed up chemical reactions and to mimic the warmer climate many suspect prevailed in the martian past, both temperature and atmospheric pressure were kept higher than those on the Red Planet today.

Magnetite exhibited no change in structure or composition in either atmosphere, which suggests that on Mars, as on Earth, the mineral simply weathers out of bedrock.

Metallic iron remained unchanged even after one year in the peroxide atmosphere, but in the water atmosphere, it underwent rapid changes. The sample turned an olive color after 19 days, was a “deep, dusky red” by day 75, and a “dark, yellowish brown” by the experiment’s end. It became increasingly crystalline, too, eventually forming the minerals siderite and goethite. Goethite can change to hematite in a waterless environment, so any goethite that formed when the martian environment was warmer and wetter may exist under layers of hematite today.

The pyrrhotite turned yellow-red after just 5 days in the peroxide atmosphere, but it took about 100 days to turn a dark, brownish red in the water atmosphere. In both cases, though, the same minerals formed: goethite, sulfur, and small amounts of iron sulfates. One of the sulfates was jarosite, which was identified at Meridiani Planum by the Opportunity rover last spring.

The scientists reported their results in the December issue of Geology. They say the experiment reveals a possible mechanism for creating these minerals on Mars without invoking features not seen there today, such as oxygen, acid vapor, or extensive bodies of surface water. — Francis Reddy

One of NASA’s most dedicated astronauts, John Young, recently retired. Another mainstay at the space agency is also calling it quits. The B-52B “mothership,” the oldest aircraft in service at NASA, will be retired following a ceremony December 17 at the Dryden Flight Research Center at Edwards Air Force Base in California.

The B-52B flew its first mission in 1955 and served as a test aircraft for its first 4 years. Following this service, the aircraft participated in the X-15 program as a launch vehicle. The X-15 program contributed to our understanding of hypersonic flight and the development of the Mercury, Gemini, and subsequent programs.

Following the X-15 program, the B-52B operated as a launch vehicle and test aircraft. Its most recent mission was March 2004, when it carried an X-43A rocket.

After it is decommissioned, the aircraft will be on display at Edwards Air Force Base.

— Jeremy McGovern