The study of craters began in 1609 when Galileo Galilei pointed his modest telescope toward the Moon. He quickly recognized that the circular areas he called “spots” were actually depressions. As the moon’s phase changed, Galileo observed the raised crater rims catching the Sun’s rays before the crater floors.

Nearly 60 years after Galileo looked at the Moon, Robert Hooke published his book Micrographia. In it, he suggested two possible origins for lunar craters, internal volcanic activity or impact from an external object. Though Hooke had experimented with musket balls and mud in making impact craters, he believed that lunar craters probably had a volcanic origin. At that time, interplanetary space was thought to be empty, and Hooke couldn’t imagine where the impact objects came from.

Impact craters are a natural lure for children. The spectacular way in which they form spurs a child’s imagination, while the features that result are easily spotted in the most modest equipment. Anyone can look up at the full Moon and identify its largest seas and craters. With a pair of binoculars, lunar mountain ridges, crater rims, and central peaks come into focus. Observing the Moon is an ideal entry point into astronomy for children — particularly because most notice its “changing face” at a very young age. I’ve heard a two-year-old refer to the crescent Moon as a “broke” Moon. He was accustomed to seeing a much larger phase.

Begin your child’s lunar lesson with some basic features. The Moon holds craters, basins, mountains, rilles, and rays. Each has its own attributes, but all are related to impacts in some way.

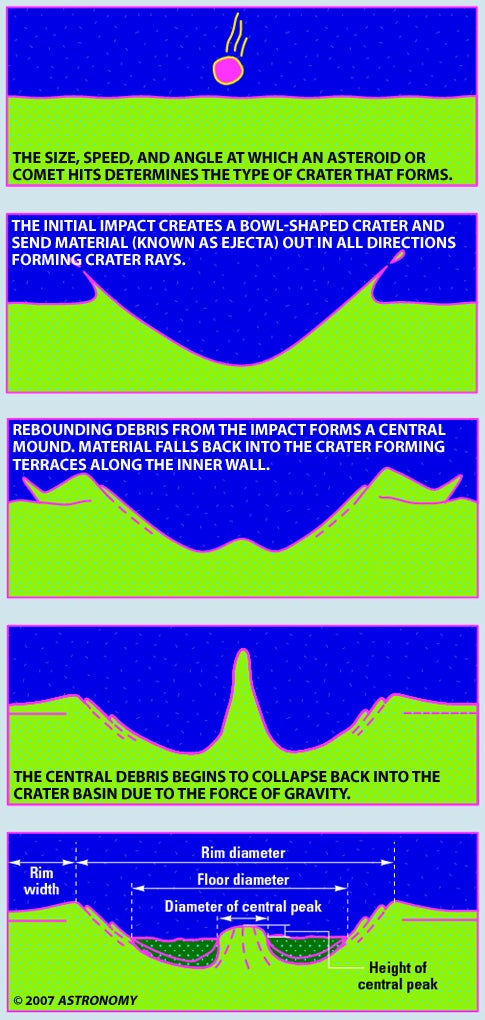

Lunar impact craters come in three basic types: simple craters, complex craters, and basins. Simple craters are what most people think of when they visualize a crater. They tend to be bowl-shaped with rounded or small, flat floors. Simple craters also have smooth rims that lack terraces. As crater diameter (measured rim to rim) increases, the resulting features become more elaborate.

Complex craters have scalloped inner walls that formed when unconsolidated rock slumped into the crater. Their most striking feature is an uplifted central peak (or peaks) that protrudes from a broad, relatively flat floor.

One of the best examples is Mare Orientale, the Eastern Sea.

The Moon isn’t the only place with a lot of craters. Some of the more complex ones exist on other planets and moons. Jupiter’s moon Callisto is a heavily cratered world with one very prominent impact. The Valhalla Basin has an extensive ring structure that surrounds the central crater. The entire ring basin measures nearly 1,900 miles across. That’s more than half of the moon’s 3,100-mile (5,000-km) diameter. If Valhalla were placed over the United States, it would stretch just past our borders with Canada and Mexico.

Another scarred Moon is tiny Mimas, which orbits Saturn. Mimas is nicknamed the “Death Star” due to its resemblance to the Star Wars ship of the same name. A large impact crater named Herschel spans one-third of the moon’s 240-mile (390-km) diameter. If the collision that formed this crater had been much stronger, Mimas would have been shattered into pieces.

If you’re like me and didn’t get enough mud-pie time as a kid, try making a few crater pies of your own. It’s guaranteed to be a hit with the kids. You’ll need an aluminum pie pan, a metal spoon, a paper cup, water, some fine clay-rich soil or drywall plaster, and newspapers to protect the table and floor from stray impacts (better yet, try this out on the driveway).

Once you’ve got the mixture to the proper consistency, scoop a small portion into the paper cup and smooth the surface of the mixture in the pie pan. With your spoon, scoop up a small glob from the cup. Stand above the pie pan and let the glob drop from the spoon. Now, if you’re feeling particularly impish, you can go back to your “food-fight” days and fling the glob from the spoon. You’ll get extra points for actually hitting the pie pan. For a more dramatic effect, sprinkle the smooth muddy surface with flour or light sand before making the craters. This may help certain features, such as crater rays, stand out in your end product.

Continue making craters by varying the size of the globs and the angle and velocity at which they hit the plate. Once the pan holds craters of different sizes and shapes, let it dry out so you can study it.

Do all the craters have central peaks and raised edges? Are there rays that lead away from the crater? What type of crater formed with a large glob that was dropped from the spoon as compared to one that was flung from the spoon? How do craters formed by small globs differ from those formed by large ones? You can find the answers in your mud-pie Moon.

Swiss cheese? Green cheese? Is it Gouda? Well … we all know the Moon isn’t made of cheese, even if residents of the “Dairy State” would like to see it that way.

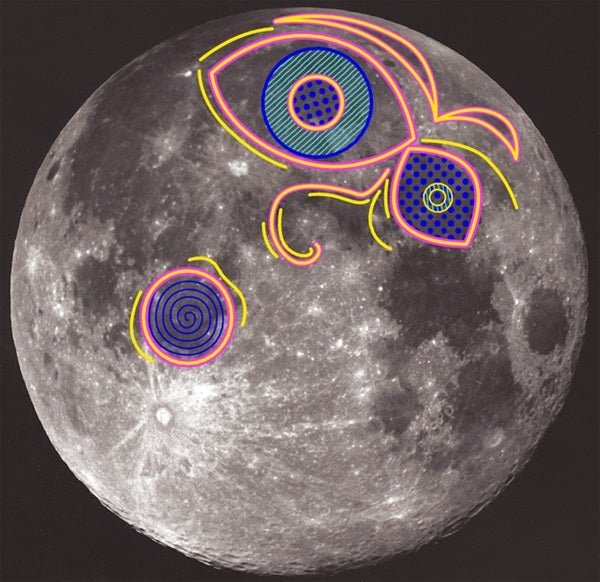

Cheese is just one of the many different images seen in the charcoal-gray, black, and white markings created by various lunar craters and basins. The most famous of these is the “Man on the Moon,” whose face looks like a jack-o’-lantern. But the man in the Moon isn’t the only figure you can find.

The Native American Haida people in British Columbia see a woman who carries a bucket, while the ancient Greeks believed the Full Moon was the goddess Selene riding her silver chariot across the sky.

Even children can be spotted on the moon. To the Vikings, the dark lunar maria represent a boy and girl who went up a hill to get a pail of water. Sound familiar? In this story, however, the pair didn’t fall down, but were whisked away to the Moon instead.

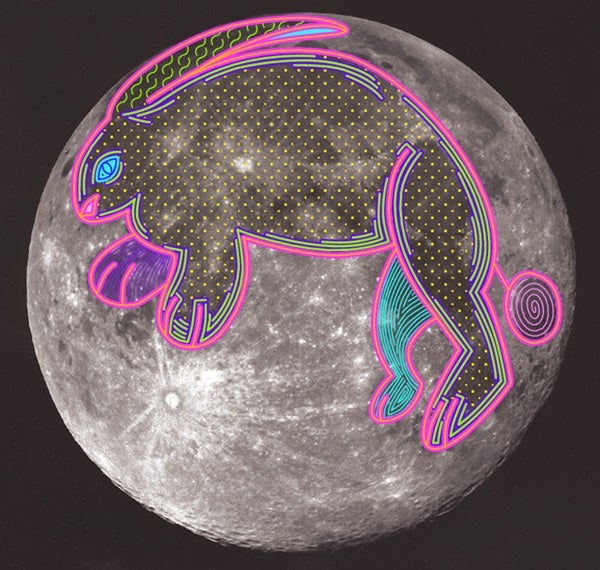

Animal figures have also been popular. The Chinese see a rabbit in the dark areas and a toad in the white. A rabbit may be the most common figure seen on the moon, with cultures in southeast Asia, Korea, and Japan, as well as the ancient Maya and Aztec civilizations all discerning a bunny’s form with ears and tail.

So, the next time there is a Full Moon, go outside and take a look. Have your child draw a picture and/or write a story of what he or she sees “in the Moon.”