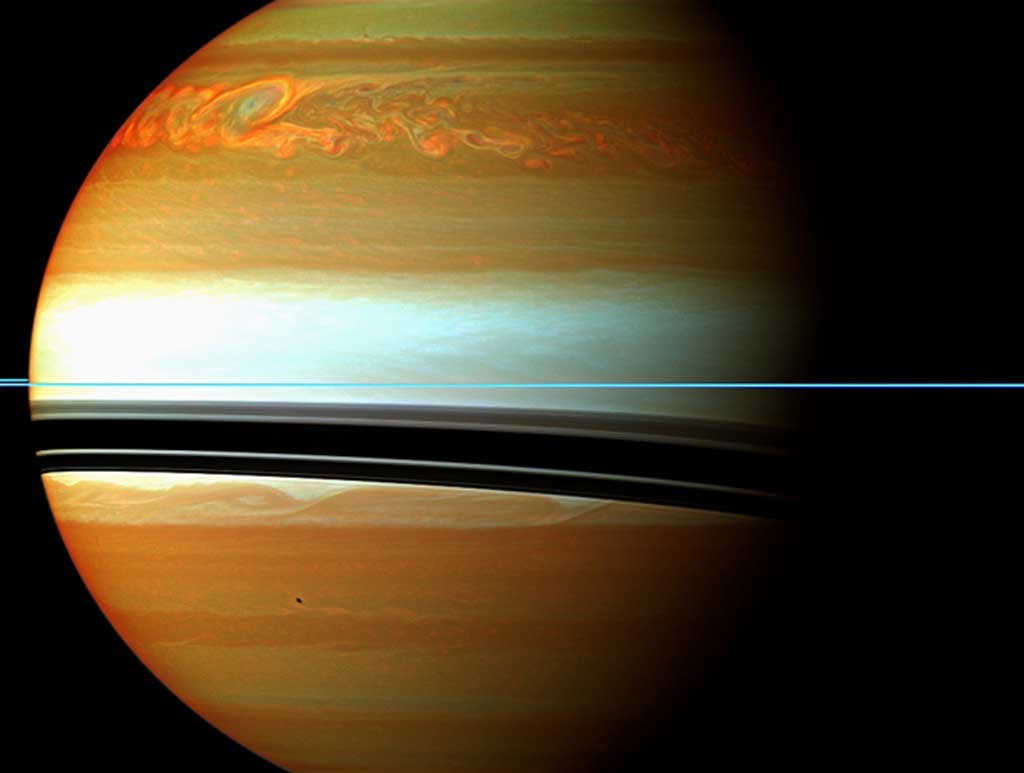

On December 5, 2010, Cassini first detected the storm that has been raging ever since. It appears at approximately 35° north latitude on Saturn. Pictures from Cassini’s imaging cameras show the storm wrapping around the entire planet, covering approximately 1.5 billion square miles (4 billion square kilometers).

The storm is about 500 times larger than the biggest storm previously seen by Cassini during several months from 2009 to 2010. Scientists studied the sounds of the new storm’s lightning strikes and analyzed images taken between December 2010 and February 2011. Data from Cassini’s radio and plasma wave science instrument showed the lightning flash rate to be as much as 10 times more frequent than during other storms monitored since Cassini’s arrival at Saturn in 2004.

“Cassini shows us that Saturn is bipolar,” said Andrew Ingersoll from the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, California. “Saturn is not like Earth and Jupiter where storms are fairly frequent. Weather on Saturn appears to hum along placidly for years and then erupts violently. I’m excited we saw weather so spectacular on our watch.”

At its most intense, the storm generated more than 10 lightning flashes per second. Even with millisecond resolution, the spacecraft’s radio and plasma wave instrument had difficulty separating individual signals during the most intense period. (Listen to the file at www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/cassini/whycassini/pia14310.html.)

Cassini has detected 10 lightning storms on Saturn since the spacecraft entered the planet’s orbit and its southern hemisphere was experiencing summer, with full solar illumination not shadowed by the rings. Those storms rolled through an area in the southern hemisphere dubbed “Storm Alley.” But the Sun’s illumination on the hemispheres flipped around August 2009 when the northern hemisphere began experiencing spring.

“This storm is thrilling because it shows how shifting seasons and solar illumination can dramatically stir up the weather on Saturn,” said Georg Fischer from the Austrian Academy of Sciences in Graz. “We have been observing storms on Saturn for almost 7 years, so tracking a storm so different from the others has put us at the edge of our seats.”

The storm’s results are the first activities of a new “Saturn Storm Watch” campaign. During this effort, Cassini looks at likely storm locations on Saturn in between its scheduled observations. On the same day that the radio and plasma wave instrument detected the first lightning, Cassini’s cameras happened to be pointed at the right location as part of the campaign and captured an image of a small, bright cloud. Because analysis on that image was not completed immediately, Fischer sent out a notice to the worldwide amateur astronomy community to collect more images. A flood of amateur images helped scientists track the storm as it grew rapidly, wrapping around the planet by late January 2011.

The new details about this storm complement atmospheric disturbances described recently by scientists using Cassini’s composite infrared spectrometer and the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope. The storm is the biggest observed by spacecraft orbiting or flying by Saturn. NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope captured images in 1990 of an equally large storm.

On December 5, 2010, Cassini first detected the storm that has been raging ever since. It appears at approximately 35° north latitude on Saturn. Pictures from Cassini’s imaging cameras show the storm wrapping around the entire planet, covering approximately 1.5 billion square miles (4 billion square kilometers).

The storm is about 500 times larger than the biggest storm previously seen by Cassini during several months from 2009 to 2010. Scientists studied the sounds of the new storm’s lightning strikes and analyzed images taken between December 2010 and February 2011. Data from Cassini’s radio and plasma wave science instrument showed the lightning flash rate to be as much as 10 times more frequent than during other storms monitored since Cassini’s arrival at Saturn in 2004.

“Cassini shows us that Saturn is bipolar,” said Andrew Ingersoll from the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, California. “Saturn is not like Earth and Jupiter where storms are fairly frequent. Weather on Saturn appears to hum along placidly for years and then erupts violently. I’m excited we saw weather so spectacular on our watch.”

At its most intense, the storm generated more than 10 lightning flashes per second. Even with millisecond resolution, the spacecraft’s radio and plasma wave instrument had difficulty separating individual signals during the most intense period. (Listen to the file at www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/cassini/whycassini/pia14310.html.)

Cassini has detected 10 lightning storms on Saturn since the spacecraft entered the planet’s orbit and its southern hemisphere was experiencing summer, with full solar illumination not shadowed by the rings. Those storms rolled through an area in the southern hemisphere dubbed “Storm Alley.” But the Sun’s illumination on the hemispheres flipped around August 2009 when the northern hemisphere began experiencing spring.

“This storm is thrilling because it shows how shifting seasons and solar illumination can dramatically stir up the weather on Saturn,” said Georg Fischer from the Austrian Academy of Sciences in Graz. “We have been observing storms on Saturn for almost 7 years, so tracking a storm so different from the others has put us at the edge of our seats.”

The storm’s results are the first activities of a new “Saturn Storm Watch” campaign. During this effort, Cassini looks at likely storm locations on Saturn in between its scheduled observations. On the same day that the radio and plasma wave instrument detected the first lightning, Cassini’s cameras happened to be pointed at the right location as part of the campaign and captured an image of a small, bright cloud. Because analysis on that image was not completed immediately, Fischer sent out a notice to the worldwide amateur astronomy community to collect more images. A flood of amateur images helped scientists track the storm as it grew rapidly, wrapping around the planet by late January 2011.

The new details about this storm complement atmospheric disturbances described recently by scientists using Cassini’s composite infrared spectrometer and the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope. The storm is the biggest observed by spacecraft orbiting or flying by Saturn. NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope captured images in 1990 of an equally large storm.