In a new study, scientists used images collected over several years by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft to discover that the heat from within the planet powers the jet streams. Condensation of water from Saturn’s internal heating led to temperature differences in the atmosphere. The temperature differences created eddies, or disturbances that move air back and forth at the same latitude, and those eddies, in turn, accelerated the jet streams like rotating gears driving a conveyor belt.

A competing theory had assumed that the energy for the temperature differences came from the Sun. That is how it works in Earth’s atmosphere.

“We know the atmospheres of planets such as Saturn and Jupiter can get their energy from only two places — the Sun or the internal heating,” said Tony Del Genio from NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York. “The challenge has been coming up with ways to use the data so that we can tell the difference.”

The new study was possible, in part, because Cassini has been in orbit around Saturn long enough to obtain the large number of observations required to see subtle patterns emerge from the day-to-day variations in weather. “Understanding what drives the meteorology on Saturn, and in general on gaseous planets, has been one of our cardinal goals since the inception of the Cassini mission,” said Carolyn Porco from the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colorado. “It is very gratifying to see that we’re finally coming to understand those atmospheric processes that make Earth similar to, and also different from, other planets.”

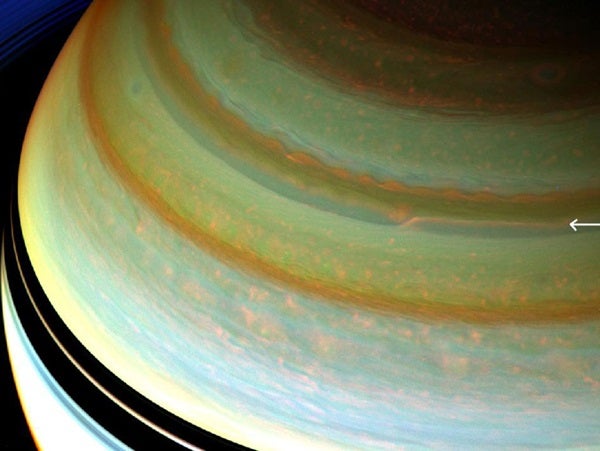

Rather than having a thin atmosphere and solid-and-liquid surface like Earth, Saturn is a gas giant whose deep atmosphere is layered with multiple cloud decks at high altitudes. A series of jet streams slice across the face of Saturn visible to the human eye and also at altitudes detectable to the near-infrared filters of Cassini’s cameras. While most blow eastward, some blow westward. Jet streams occur on Saturn in places where the temperature varies significantly from one latitude to another.

Thanks to the filters on Cassini’s cameras, which can see near-infrared light reflected to space, scientists now have observed the Saturn jet stream process for the first time at two different low altitudes. One filtered view shows the upper part of the troposphere, a high layer of the atmosphere where Cassini sees thick, high-altitude hazes, and where heating by the Sun is strong. Views through another filter capture images deeper down, at the tops of ammonia ice clouds, where solar heating is weak but closer to where weather originates. This is where water condenses and makes clouds and rain.

In the new study, scientists used automated cloud tracking software to analyze the movements and speeds of clouds seen in hundreds of Cassini images from 2005 through 2012.

“With our improved tracking algorithm, we’ve been able to extract nearly 120,000 wind vectors from 560 images, giving us an unprecedented picture of Saturn’s wind flow at two independent altitudes on a global scale,” said John Barbara, also from the Goddard Institute for Space Studies. The team’s findings provide an observational test for existing models that scientists use to study the mechanisms that power the jet streams.

By seeing for the first time how these eddies accelerate the jet streams at two different altitudes, scientists found that the eddies were weak at the higher altitudes where previous researchers had found that most of the Sun’s heating occurs. The eddies were stronger deeper in the atmosphere; thus the scientists could discount heating from the Sun and infer instead that the internal heat of the planet is ultimately driving the acceleration of the jet streams, not the Sun. The mechanism that best matched the observations would involve internal heat from the planet stirring up water vapor from Saturn’s interior. That water vapor condenses in some places as air rises and releases heat as it makes clouds and rain. This heat provides the energy to create the eddies that drive the jet streams.

The condensation of water was not actually observed; most of that process occurs at lower altitudes not visible to Cassini. But the condensation in mid-latitude storms does happen on both Saturn and Earth. Storms on Earth — the low- and high-pressure centers on weather maps — are driven mainly by the Sun’s heating and do not mainly occur because of the condensation of water, Del Genio said. On Saturn, the condensation heating is the main driver of the storms, and the Sun’s heating is not important.