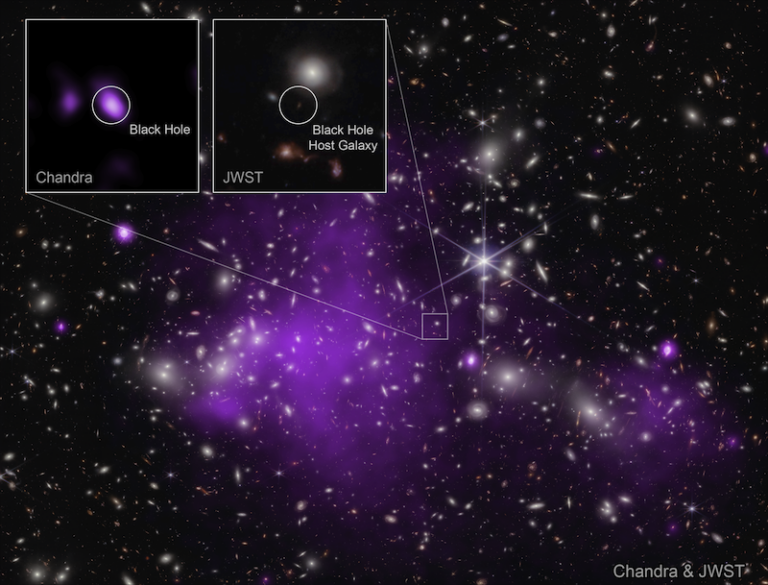

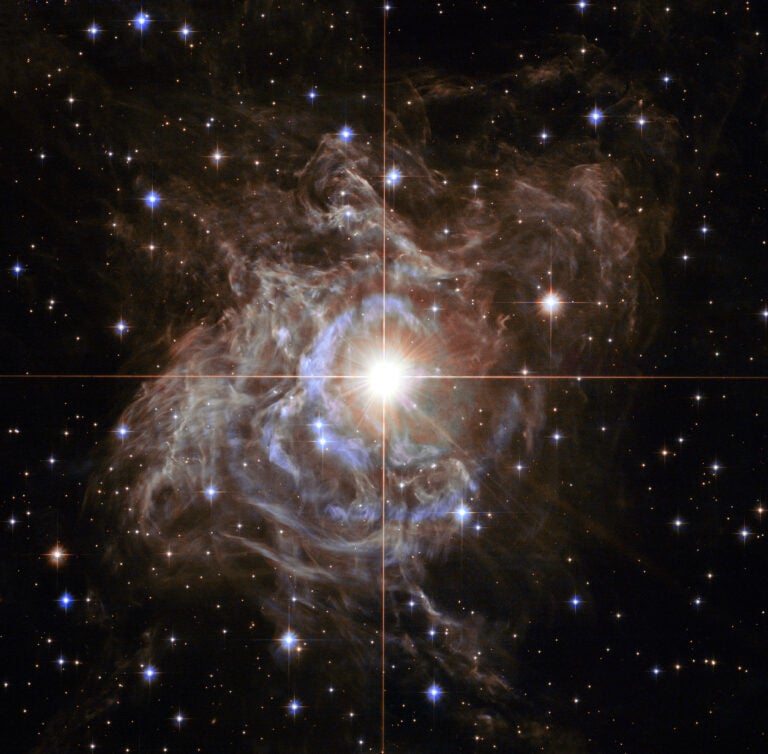

Two teams of astronomers, working independently, observed three such exploding stars, called supernovae. Their light was amplified by the immense gravity of massive galaxy clusters in the foreground — a phenomenon called gravitational lensing. Astronomers use the gravitational lensing effect to search for distant objects that might otherwise be too faint to see, even with today’s largest telescopes.

“We have found supernovae that can be used like an eye chart for each lensing cluster,” said Saurabh Jha of Rutgers University in Piscataway, New Jersey. “Because we can estimate the intrinsic brightness of the supernovae, we can measure the magnification of the lens.”

At least two of the supernovae appear to be a special type of exploding star called type Ia supernovae, prized by astronomers because they have a consistent level of peak brightness that makes them a reliable tool for estimating distances.

Astronomers from the CLASH team and the Supernova Cosmology Project are using these supernovae in a new method for measuring the magnification, or prescription, of the gravitational lenses. With these prescriptions, astronomers are now equipped to make increasingly accurate observations of objects in the distant early universe and better understand the structure of galaxy clusters, including its distribution of dark matter.

The power of a galaxy cluster as a gravitational lens depends on the total amount of matter in the cluster, including dark matter, which is the source of most of a cluster’s gravity. Astronomers develop maps that estimate the location and amount of dark matter in a cluster by looking at the amount of distortion seen in more distant lensed galaxies. The maps provide the prescriptions — how much distant objects behind the cluster are magnified when their light passes through the cluster.

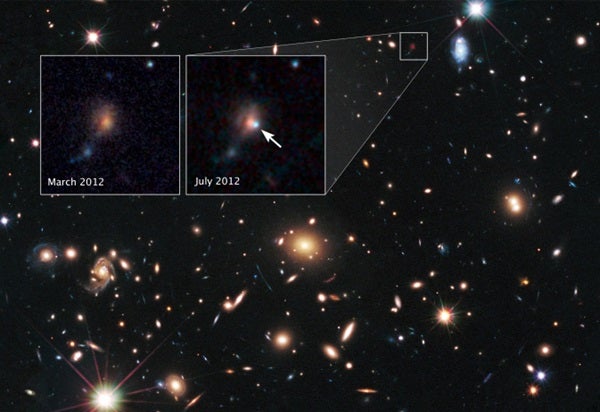

The three supernovae in the Hubble study were each gravitationally lensed by a different cluster of galaxies. The teams measured the brightness of each supernova, with and without the effects of lensing. The difference between the two measurements constitutes the amount of magnification because of gravitational lensing. From the final measurements, one of the three supernovae stood out, with an apparent magnification of about two times.

The supernovae were discovered in the CLASH survey, a Hubble census that probed the distribution of dark matter in 25 galaxy clusters. The three supernovae exploded between 7 billion and 9 billion years ago, when the universe was slightly more than half its current age of 13.8 billion years old.

To perform their analyzes, both teams used observations in visible light made by Hubble’s Advanced Camera for Surveys and in infrared light made by the telescope’s Wide Field Camera 3. Each team then compared its results with independent theoretical models of the clusters’ dark-matter content, concluding that the predictions fit the models.

Now that researchers have proven the effectiveness of this method of cosmic magnification, they are searching for more type Ia supernovae hiding behind large galaxy clusters. Astronomers estimate they would need about 20 supernovae spread out behind a single cluster to create a map of an entire cluster of galaxies.

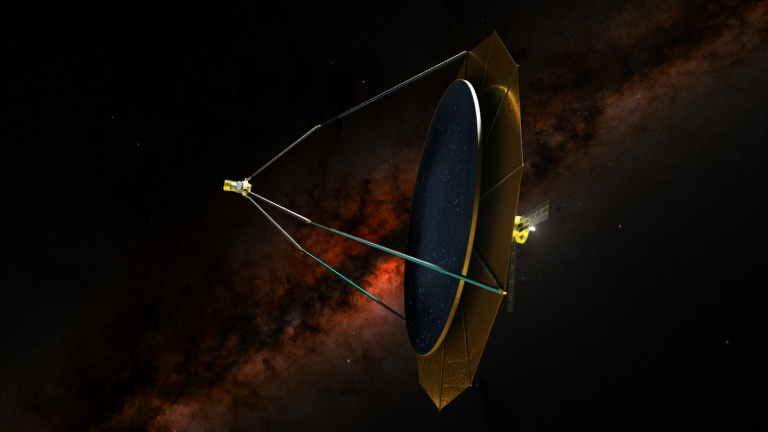

They are optimistic that Hubble and future telescopes, such as NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, will identify more of these unique exploding stars.