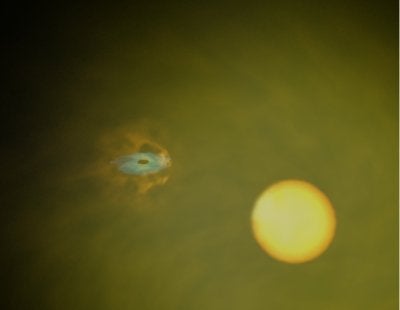

Just in time for Halloween, astronomers have hunted down a stellar vampire with a spooky new type of lair lurking in the galactic neighborhood. Hidden from view until now, the secretive black hole and its hapless prey, a massive companion star, appear to be collectively entombed in an eerie cocoon of gas and dust. Piercing through this obscuring shroud, first with gamma-ray and then x-ray vision, orbiting telescopes have revealed a strange new class of astronomical object with this discovery.

Researchers believe that the newfound black hole is feeding on gas sucked off the nearby massive star. While such bloodsucking relationships are nothing new to astronomers (about 300 have been catalogued), IGR J16318-4848 proved to be more illusive than the others. As the stellar gas becomes accreted by the voracious monster, an eerie, dense cocoon forms around the binary system. This enveloping bubble of cold gas blocked most of the emitted energy, keeping the system’s true identity under wraps — until now.

Emitting only the most energetic radiation, IGR J16318-4848 was first spotted by Europe’s new gamma-ray observatory, Integral, in January 2003 during a sweep of the galactic plane. Though it was known to be in our galaxy, astronomers remained baffled as to the exact nature of this high-energy source.

To solve the mystery, a team of European astrophysicists used the XMM-Newton space observatory to observe IGR J16318-4848 and discovered a shell of dense material, equivalent in size to Earth’s orbit, enveloping the odd object.

“Only photons with the highest energies could escape from that cocoon,” explains team leader Roland Walter of the Integral Science Data Center in Switzerland. “IGR J16318-4848 has therefore not been detected by surveys performed at lower energies, nor by previous gamma-ray missions that were much less sensitive than Integral.”

Just as the authors of the study are set to publish their findings in the November issue of Astronomy and Astrophysics, they are already hot on the trail of two more similar sources that are embedded in obscuring material. Citing the two spacecraft’s complementary talents, the researchers hope to use INTEGRAL and XMM-Newton in tandem to make additional observations of other presently hidden black holes.