An international team of astronomers, including Michael Kramer from the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Bonn, Germany, has studied the behavior of natural cosmic clocks and discovered a way to potentially turn them into the best timekeepers in the universe. The scientists made their breakthrough using decade-long observations from the 249-foot (76 meters) Lovell radio telescope at the University of Manchester’s Jodrell Bank Observatory in England to track the radio signals of an extreme type of star known as pulsars. This new understanding of pulsar spin-down could improve the chances to use the fastest spinning pulsars in order to make the first direct detection of ripples, known as gravitational waves, in the fabric of space-time.

Radio pulsars have been studied in detail since their discovery in 1967, and their rotational stability has led to the discovery of the first extrasolar planets and provided tests for our theories of the universe. However, the rotational stability is not perfect, and until now, slight irregularities in their rotation have significantly reduced their usefulness as precision tools.

The team, led by Andrew Lyne from the Jodrell Bank Center for Astrophysics, has used observations from the Lovell telescope to explain these variations and to demonstrate a method by which they may be corrected. “Mankind’s best clocks all need corrections, perhaps for the effects of changing temperature, atmospheric pressure, humidity, or local magnetic field,” said Lyne. “Here, we have found a potential means of correcting an astrophysical clock”.

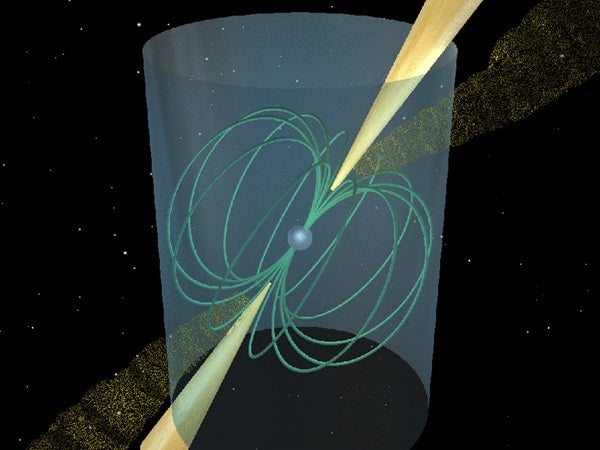

The rate at which all pulsars spin is known to be slowly decreasing. What the team has found is that the deviations arise because there are actually two spin-down rates, not one, and that the pulsar switches between them, abruptly and rather unpredictably. The team’s second vital discovery is “that these changes are associated with a change in the shape of the pulse, or tick, emitted by the pulsar,” said George Hobbs from the Australia Telescope National Facility. “Because of this, precision measurements of the pulse shape at any particular time indicate exactly what the slowdown rate is and allow the calculation of a ‘correction.’ This significantly improves their properties as clocks.”

“These results give a completely new insight into the extreme conditions near neutron stars and offer the potential for improving our already very precise experiments in gravitation,” said Kramer.

It is hoped that this new understanding of pulsar spin-down will improve the chances that the fastest spinning pulsars will be used to make the first direct detection of ripples, known as gravitational waves, in the fabric of space-time. “Many observatories around the world are attempting to use pulsars in order to detect the gravitational waves that are expected to be created by supermassive binary black holes in the universe,” said Ingrid Stairs from the University of British Columbia in Canada. “With our new technique, we may be able to reveal the gravitational wave signals that are currently hidden because of the irregularities in the pulsar rotation.”