Key Takeaways:

“The environment around this quasar is unique in that it’s producing this huge mass of water,” said Matt Bradford from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “It’s another demonstration that water is pervasive throughout the universe, even at the very earliest times.”

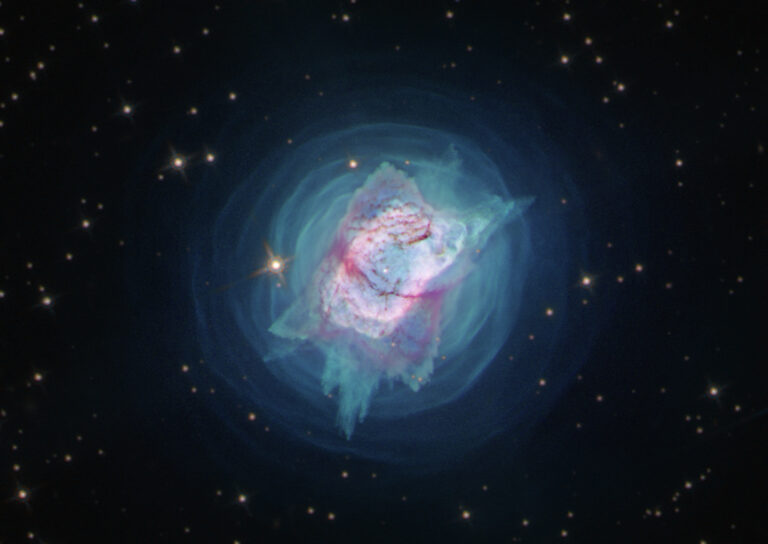

A quasar is powered by an enormous black hole that steadily consumes a surrounding disk of gas and dust. As it eats, the quasar spews out huge amounts of energy. Both groups of astronomers studied a particular quasar called APM 08279+5255, which harbors a black hole 20 billion times more massive than the Sun and produces as much energy as a thousand trillion Suns.

Astronomers expected water vapor to be present even in the early, distant universe, but had not detected it this far away before. There’s water vapor in the Milky Way, although the total amount is 4,000 times less than in the quasar because most of the Milky Way’s water is frozen in ice.

Water vapor is an important trace gas that reveals the nature of the quasar. In this particular quasar, the water vapor is distributed around the black hole in a gaseous region spanning hundreds of light-years in size. Its presence indicates that the quasar is bathing the gas in X-rays and infrared radiation, and that the gas is unusually warm and dense by astronomical standards. Although the gas is at a chilly –63° Fahrenheit (–53° Celsius) and is 300 trillion times less dense than Earth’s atmosphere, it’s still 5 times hotter and 10 to 100 times denser than what’s typical in galaxies like the Milky Way.

Measurements of the water vapor and of other molecules, such as carbon monoxide, suggest there is enough gas to feed the black hole until it grows to about six times its size. Whether this will happen is not clear, the astronomers say, because some of the gas may end up condensing into stars or might be ejected from the quasar.

Bradford’s team made their observations starting in 2008, using an instrument called “Z-Spec” at the California Institute of Technology’s Submillimeter Observatory, a 33-foot (10 meters) telescope near the summit of Mauna Kea in Hawaii. Follow-up observations were made with the Combined Array for Research in Millimeter-Wave Astronomy (CARMA), an array of radio dishes in the Inyo Mountains of Southern California.

The second group, led by Dariusz Lis from Caltech, used the Plateau de Bure Interferometer in the French Alps to find water. In 2010, Lis’ team serendipitously detected water in APM 8279+5255, observing one spectral signature. Bradford’s team was able to get more information about the water, including its enormous mass, because they detected several spectral signatures of the water.

“The environment around this quasar is unique in that it’s producing this huge mass of water,” said Matt Bradford from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “It’s another demonstration that water is pervasive throughout the universe, even at the very earliest times.”

A quasar is powered by an enormous black hole that steadily consumes a surrounding disk of gas and dust. As it eats, the quasar spews out huge amounts of energy. Both groups of astronomers studied a particular quasar called APM 08279+5255, which harbors a black hole 20 billion times more massive than the Sun and produces as much energy as a thousand trillion Suns.

Astronomers expected water vapor to be present even in the early, distant universe, but had not detected it this far away before. There’s water vapor in the Milky Way, although the total amount is 4,000 times less than in the quasar because most of the Milky Way’s water is frozen in ice.

Water vapor is an important trace gas that reveals the nature of the quasar. In this particular quasar, the water vapor is distributed around the black hole in a gaseous region spanning hundreds of light-years in size. Its presence indicates that the quasar is bathing the gas in X-rays and infrared radiation, and that the gas is unusually warm and dense by astronomical standards. Although the gas is at a chilly –63° Fahrenheit (–53° Celsius) and is 300 trillion times less dense than Earth’s atmosphere, it’s still 5 times hotter and 10 to 100 times denser than what’s typical in galaxies like the Milky Way.

Measurements of the water vapor and of other molecules, such as carbon monoxide, suggest there is enough gas to feed the black hole until it grows to about six times its size. Whether this will happen is not clear, the astronomers say, because some of the gas may end up condensing into stars or might be ejected from the quasar.

Bradford’s team made their observations starting in 2008, using an instrument called “Z-Spec” at the California Institute of Technology’s Submillimeter Observatory, a 33-foot (10 meters) telescope near the summit of Mauna Kea in Hawaii. Follow-up observations were made with the Combined Array for Research in Millimeter-Wave Astronomy (CARMA), an array of radio dishes in the Inyo Mountains of Southern California.

The second group, led by Dariusz Lis from Caltech, used the Plateau de Bure Interferometer in the French Alps to find water. In 2010, Lis’ team serendipitously detected water in APM 8279+5255, observing one spectral signature. Bradford’s team was able to get more information about the water, including its enormous mass, because they detected several spectral signatures of the water.