Astronomers announced today that they have discovered 33 pairs of waltzing black holes in distant galaxies. This result shows that supermassive black hole pairs are more common than previously known from observations. Also, the black hole pairs can be used to estimate how often galaxies merge with each other.

Astronomical observations have shown that nearly every galaxy has a central supermassive black hole (with a mass of a million to a billion times the mass of the Sun), and galaxies commonly collide and merge to form new, more massive galaxies. As a consequence of these two observations, a merger between two galaxies should bring two supermassive black holes to the new, more massive galaxy formed from the merger. The two black holes gradually in-spiral toward the center of this galaxy, engaging in a gravitational tug-of-war with the surrounding stars. The result is a black hole dance, like the one expected to occur in our own Milky Way Galaxy in about 3 billion years when it collides with the Andromeda Galaxy.

Astronomers expect many such waltzing supermassive black holes in the universe, but until recently only a handful had been found. Julia Comerford, from the University of California at Berkeley, and her colleagues announced the discoveries of 33 new pairs of waltzing supermassive black holes, which help alleviate the discrepancy between the expected and observed numbers of black hole pairs.

Comerford and her colleagues observed the waltzing black holes that have gas collapsing onto them, and this gas releases energy and powers each black hole as an active galactic nucleus (AGN).

The team of astronomers used two new techniques to discover the waltzing black holes. First, they identified the objects by the velocities of their dances in the host galaxy. The host galaxy is the ballroom floor, and the astronomers measured redshifted light from a black hole dancer if it danced away from the telescope and blue-shifted light if it danced towards the telescope. By searching for the redshifted and blueshifted light that is a signature of black hole dances, Comerford and her colleagues discovered 32 waltzing supermassive black hole pairs in the DEEP2 Galaxy Redshift Survey — a survey of 50,000 galaxies observed with the Deep Imaging Multi-Object Spectrograph (DEIMOS) on the 10-meter Keck II Telescope on Mauna Kea, Hawaii. The team clocked each black hole dance at a velocity of a few hundred miles per second, and in each case they measured the distance between the two black holes to be 3,000 light-years (1/8 the distance from the Sun to the center of the Milky Way Galaxy). The black holes are located in galaxies at distances 4 to 7 billion light-years from Earth.

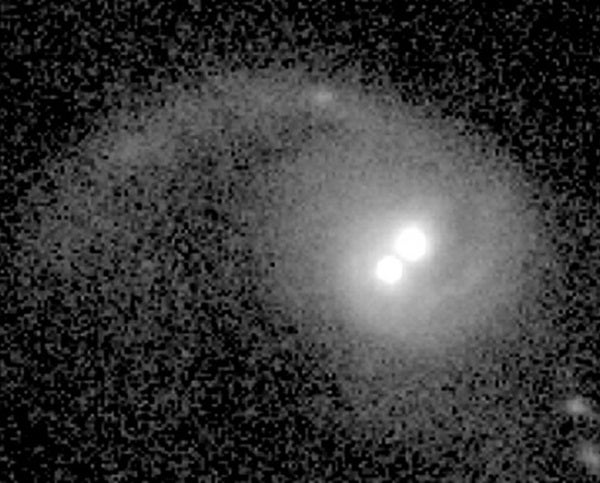

The team developed their second technique for identifying waltzing black holes through a chance discovery of a curious-looking galaxy. While visually inspecting images of galaxies taken with the Advanced Camera for Surveys on the Hubble Space Telescope, the team noticed a galaxy with a tidal tail of stars, gas, and dust, an unmistakable sign that the galaxy had recently merged with another galaxy, and the galaxy also featured two bright nuclei near its center. The team recognized that the two bright nuclei might be the AGNs of two waltzing black holes, a hypothesis seemingly supported by the recent galaxy merger activity evinced by the tidal tail. To test this hypothesis, the team obtained a spectrum of the galaxy with the DEIMOS spectrograph on the 10-meter Keck II Telescope.

The spectrum showed that the two central nuclei in the galaxy were indeed both AGNs, supporting the team’s hypothesis that the galaxy has two supermassive black holes. The black holes may be waltzing within the host galaxy, or the galaxy may have a recoiling black hole kicked out of the galaxy by gravity wave emission. Additional observations are necessary to distinguish between these explanations.

The galaxy called COSMOS J100043.15+020637.2 is part of the Cosmological Evolution Survey (COSMOS), and it is located at a distance of 4 billion light-years from Earth. The team measured that the distance between the two black holes is 8,000 light-years (one-third the distance from the Sun to the center of the Milky Way Galaxy).

Using the techniques of searching for waltzing supermassive black holes by their velocities and obtaining spectra of galaxies that show two bright central nuclei and evidence of recent galaxy mergers, Comerford and her colleagues discovered a total of 33 pairs of supermassive black holes in distant galaxies. These discoveries “show that dual supermassive black hole systems are much more common than previously known from observations,” said Comerford. The dual supermassive black hole pairs can in turn be used to estimate how often galaxies merge, and the team concludes that red galaxies from between 4 and 7 billion years ago underwent 3 mergers every billion years.