Key Takeaways:

Getting to know more about David Helfand

David Helfand is the chair of the Columbia University Department of Astronomy and the co-director of the Columbia Astrophysics Laboratory.

Greatest challenge facing education today: Anti-intellectual, self-obsessed, media-stupefied, endlessly entitled students who, through criminally misguided initiatives such as All Children Left Behind — my translation of the legislation’s title — have been robbed of intellectual curiosity and made to truly believe that, as one said to me recently, they are “paying for a degree, not an education.” Typing into the upper-left-hand corner of one’s web browser has become a substitute for thinking. I am not at all certain this is a challenge we will overcome.

Greatest challenge facing astronomy today: Anti-intellectual, self-delusional, media-obsessed, permanently entitled politicians — and a similarly benighted electorate — who fail completely to appreciate the critical economic and cultural roles science plays in modern society.

Biggest pet peeve (astronomy related or otherwise): Anti-intellectual, self-obsessed, media-saturated … Are you starting to get the picture?

More questions for Lisa Randall

Lisa Randall is a professor of physics at Harvard University and the author of Warped Passages: Unraveling the Mysteries of the Universe’s Hidden Dimensions (ECCO Press, 2005).

What is the “coolest” thing you’ve learned through your research?

Perhaps the craziest thing I discovered with my collaborator Raman Sundrum is that there can be extra dimensions of the universe that are infinite in size and still cannot be seen. It’s obvious that tiny stuff can be hidden — it was more surprising that something infinitely big can be invisible.

If you had to choose, would you rather be the one doing the research or the one out sharing/explaining findings with the general public?

I would be doing physics. Nothing compares with discovery. If I were interested only in communications, there would be much simpler ways to go than communicating science! Fortunately I don’t have to choose, and I like the combination because it allows me to do science and connect to a larger world.

An extended day in the life of Matt Mountain

Matt Mountain is the director of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore.

6:30 a.m.: My wife and I stagger out of bed. Whoever is feeling bravest gives the kids first warning of an impending new school day.

7 a.m.: Sit for 15 minutes of peace with my wife watching the squirrels raiding the bird feeder. Check e-mail to see if the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) had problems overnight. Everything looks fine. Clearly, the redundant side of the electronics data controller switched on a few days ago is still working.

8 a.m.: The chaos of kids finding clothes and homework and grabbing breakfast ends as my wife hustles them out the door. First scan of the news, the NASA gossip sites, and a harder look at e-mail. While running with the dog, “meditate” on what I’m going to say at the opening session of the International Virtual Observatory Alliance Interoperability Workshop that the institute is hosting this week.

9:15 a.m.: Call my assistant, Pam, to check in on the day and send her my introductory words for the workshop. Leap into the car and just make it in time to open the workshop thanks to Pam meeting me in the lobby with my badge and newly printed script.

10:10 a.m.: Get distracted by the imminent press release announcing the first direct image of a planet that the Hubble made some months back. Arrive at first “tag-up” of the day with the HST mission team 10 minutes late. Discuss how we should approach the science priorities for the upcoming Hubble servicing mission.

11 a.m.: Weekly “tag-up” with the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) mission team. Hear a briefing on some recent reviews on how data will get compressed for transmission across the million miles from JWST’s location in space back to Earth — a key science concern.

12 p.m.: Lunch with some of the new staff we have hired this year. My wife calls to remind me to pick up my daughter tonight.

1 p.m.: Switch to “Administrator mode” — the institute is responsible for the health and welfare of the nearly 500 people who work here. Discuss ways to keep our medical cost within reasonable bounds and hear about the latest round of incoming federal auditing procedures. Time to absorb more e-mail, sign correspondence, and look at the travel schedule Pam has organized for next week: California; Washington, D.C.; Goddard Space Flight Center; and an evening event at the Maryland Space Business Round Table. I hope I remembered to tell my wife.

2 p.m.: E-mail from my daughter: “Dad, don’t forget to pick me up tonight.” Look at slides for a talk I must give next week and download images on the Hubble planetary discovery.

3:30 p.m.: Run downstairs for weekly visiting colloquium speaker in Bahcall Auditorium; this week’s speech is called “First Galaxies”.

4:30 p.m.: See the latest “widgets” our folks have put into our collaboration with Google, Sky in Google Earth. Receive a text message from Pam as she heads home for the day reminding me about my 5 p.m. meeting and telling me: “Don’t to forget to pick up your daughter.”

5 p.m.: Attend meeting about our study on a potential next-generation telescope beyond JWST (call it the “Next Big Thing” [NBT]).

5:45 p.m.: Review a wonderful book on Hubble, but realize I have only 15 minutes to pick up my daughter.

9 p.m.: Supper done and the kids’ homework nearing completion, my wife and I catch up on the news and any TV programs stored away on the DVR. Start to download a large presentation on the “NBT” discussed this afternoon.

11 p.m.: Still looking through presentation on what a 16-meter telescope in space can do. Take one last look at e-mail and remember that tomorrow is the announcement about the Hubble planetary discovery — it should be a good day.

Astro fascinations: Ann Hornschemeier

Ann Hornschemeier is an astronomer at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center Laboratory for X-ray Astrophysics in Greenbelt, Maryland, and an adjunct faculty member at Johns Hopkins University.

I describe myself as an X-ray astronomer, but I believe we’re on the threshold of an era where such a narrow label will be inadequate.

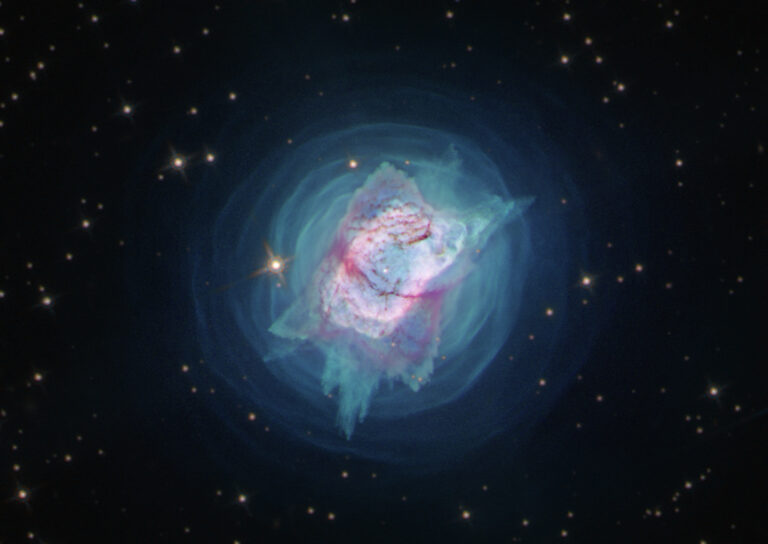

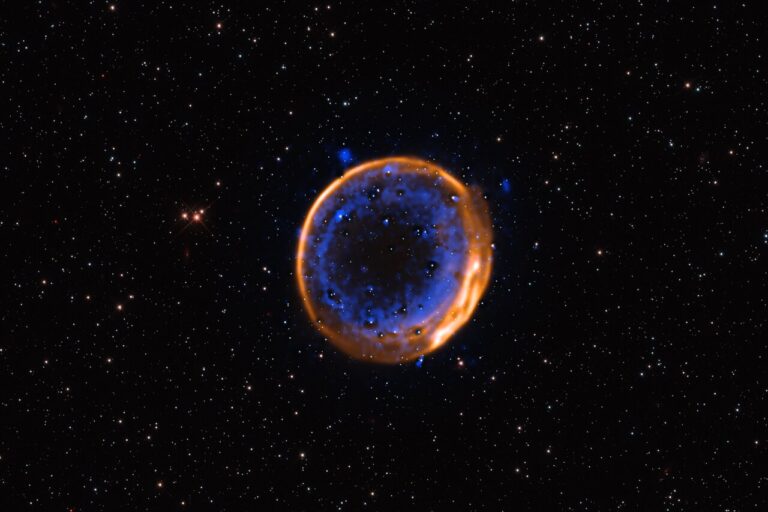

Today, an army of people is studying star formation in galaxies. X-ray astronomy is just one of many specialties that enable a multiwavelength attack on the big astrophysical questions of our time. For example, the starburst galaxies I study emit most of their radiation as infrared, visible, and ultraviolet light. Their more modest X-ray emission usually arises from accreting binary systems containing neutron stars or black holes. Because the X-ray emission is relatively weak, I must depend on multiwavelength data to place the measurements into proper context (e.g., how massive is this galaxy?).

What’s amazing is that we can take a census of X-ray binary populations in galaxies up to 8 billion light-years away — at a time when the universe was less than half its current age. Coupling this information with the more plentiful data at other wavelengths helps astronomers understand how stars form and die.

We thus need to work with experts who really know how to use the data analysis tools for specific wavelength bands and instruments. Just within my small research team here at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, scientists and students work with data from ultraviolet instruments on the Swift and GALEX satellites, various ground-based optical instruments, Hubble, and Spitzer, as well as from the Chandra and XMM-Newton X-ray observatories. The different techniques required guarantee that the people come from a diverse set of scientific backgrounds and really keep the astrophysics discussions interesting!

Multiwavelength astronomy combines the best-available information in every part of the spectrum to let us see what’s really going on. It’s how we learn the most about the universe.