(Editor’s note: This article was updated Monday, Oct. 30, 2023, with information from a study in Nature Geoscience. The study shows that fine particles kicked up from the impact may have blocked the sun and prevented photosynthesis for up to two years. Katherine Sanderson writes a helpful summary of the study here on nature.com.)

Some 66 million years ago, a city-size asteroid barreled through Earth’s atmosphere and slammed into the shallow waters off the Yucatán Peninsula in the Gulf of Mexico. The cosmic artillery strike gouged a 125-mile-wide (200 km) crater in Earth surface, lofting plumes of vaporized rock and debris into the air that globally blocked out views of the Sun for years or decades. After the initial blast, the reduced sunlight caused Earth’s surface temperature to plummet by as much as 50 degrees Fahrenheit (28 degrees Celsius), aiding in a mass extinction that killed 75 percent of life on Earth.

But eventually, the dust settled.

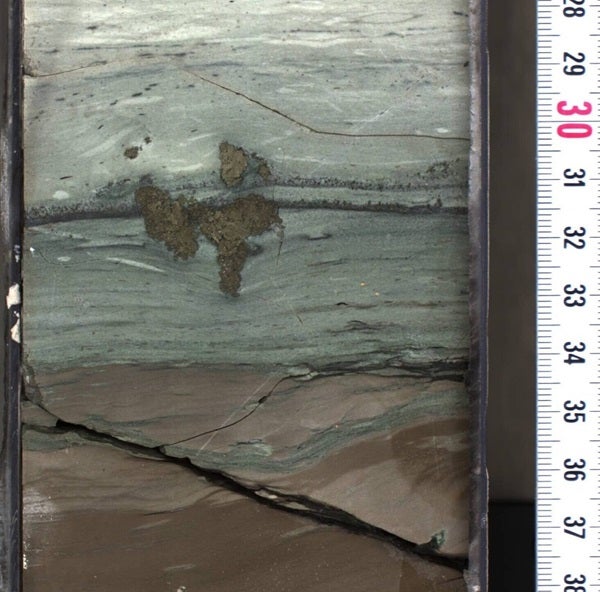

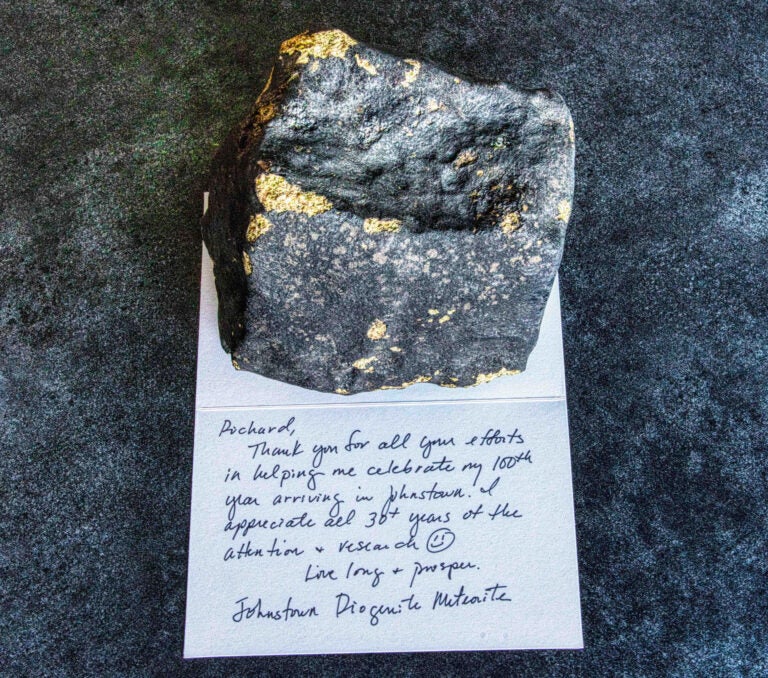

Fast forward to the 1980s, and scientists uncovered traces of asteroid dust, finding it scattered around the globe within the same geological layer that corresponds to the dinosaurs’ extinction. In the following decade, Chicxulub Crater was discovered in the Gulf of Mexico. And because the crater appeared to be the same age as the global rock layer enriched with asteroid dust, researchers were fairly certain they had the story of the dinosaurs’ demise figured out.

Now, a new study seems to have officially closed the case for good.

“We are now at the level of coincidence that geologically doesn’t happen without causation,” added Sean Gulick, a professor at UT Jackson School of Geoscience and co-author of the study.Details on the asteroid dust found in Chicxulub Crater were published in Science Advances.