Key Takeaways:

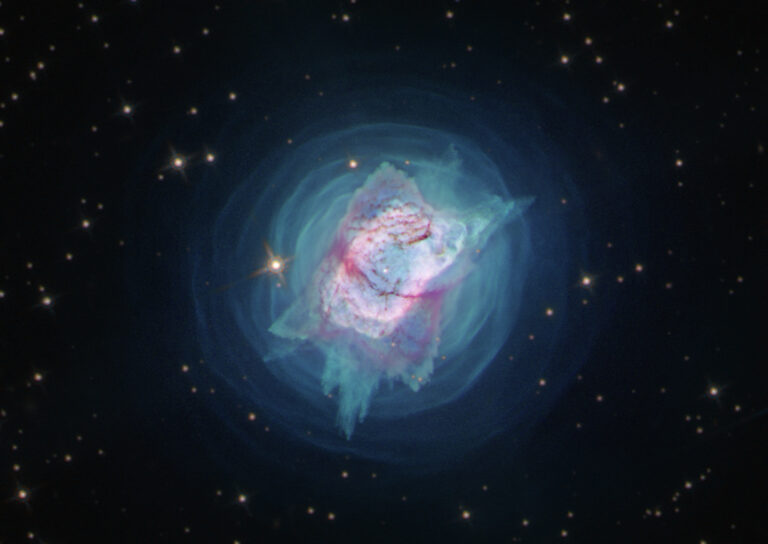

Brilliant Jupiter gleams among the stars of Taurus, just northeast of the Hyades star cluster. This view shows the planet’s position at midmonth, but it doesn’t move far during November’s 30 days. Astronomy: Roen Kelly

Jupiter approaches its peak during November and shines brilliantly among the background stars of Taurus nearly all night. Venus and Saturn court each other in the morning sky late this month, a spectacular union that places them within the same low-power telescopic field.

Meanwhile, observers in northern Australia will be treated to the year’s only total solar eclipse the morning of November 14. Two weeks later, a penumbral lunar eclipse occurs across Australia, the Pacific Ocean, and parts of North America, Europe, Africa, and Asia. As the eclipse closes out the month, Mercury emerges from the solar glow before dawn.

We begin our tour during evening twilight. Mars hardly changes position relative to your local horizon in November. It lies about 10° high in the southwest an hour after the Sun goes down and sets an hour later. It shines steadily all month, too, at magnitude 1.2.

The Red Planet maintains its appearance for two reasons. First, it moves almost as quickly as the Sun does with respect to the background stars, so it doesn’t lose much ground to our star. Second, the angle of the ecliptic — the apparent path of the Sun and planets across the sky — to the horizon steepens just enough to compensate for Mars’ decreasing solar distance.

The planet spends early November in Ophiuchus before crossing into Sagittarius. On the evening of November 27, Mars lies less than a Full Moon’s width southwest of the fine globular cluster M22. Through a telescope at low power, the cluster’s misty white glow contrasts nicely with the orange-colored planet. Unfortunately, Mars itself shows little detail in any scope. The planet presents a shimmering disk just 4″ across.

Once darkness settles in, you can find Neptune almost due south and about halfway to the zenith. The distant world glows at magnitude 7.9, bright enough to glimpse through binoculars. You can find it 0.4° south-southwest of 38 Aquarii, on an imaginary line joining this 5th-magnitude star with 4th-magnitude Iota (ι) Aqr. Under a sufficiently steady sky, a telescope reveals Neptune’s blue-gray disk, which measures 2.3″ in diameter.

Io and its shadow traverse Jupiter’s disk the night of November 7/8. The dark shadow stands out better against the planet’s bright cloud tops. Astronomy: Roen Kelly

Uranus lies one constellation east of Neptune in the southern part of Pisces the Fish. It appears in the southeastern sky as darkness falls and due south around midevening. The planet glows at magnitude 5.8, which brings it within easy range of binoculars and even into naked-eye visibility under a dark sky.

To find Uranus, start with the Great Square of Pegasus. Alpheratz and Algenib (Alpha [α] Andromedae and Gamma [γ] Pegasi, respectively) form the eastern side of this asterism, with Algenib 14° south of its neighbor. Uranus lies the same distance south of Algenib.

Don’t confuse the planet with the similarly bright star 44 Piscium. Uranus appears 1.5° west-southwest of this star in early November; the gap widens to 2.1° late in the month. A slightly fainter star stands 0.6° north of the planet during November’s final week. You can remove any question as to which object is Uranus by pointing a telescope that way. Only Uranus shows a blue-green disk, which spans 3.6″.

The subtle charms of Neptune and Uranus in the early evening give way to the dynamic appeal Jupiter brings a little later. The dazzling planet rises about two hours after sunset in early November and during twilight by midmonth. A bright gibbous Moon appears about 1° from Jupiter on the evenings of November 1 and 28.

Although the massive world doesn’t reach opposition until early December, its appearance during November nearly matches its peak. Jupiter brightens to magnitude –2.8 by midmonth, making it the night sky’s brightest point of light until Venus rises in the wee hours. There’s no mistaking the giant planet for any of the stars in Taurus the Bull, where it lies a few degrees northeast of the V-shaped Hyades star cluster.

As great as Jupiter appears to naked eyes, it looks even better through a telescope. The planet spans 48.0″ in mid-November, a nearly imperceptible 0.5″ smaller than its opposition diameter. And there’s always plenty to see in the jovian atmosphere. The best views come when the planet rides high in the sky from late evening until past midnight.

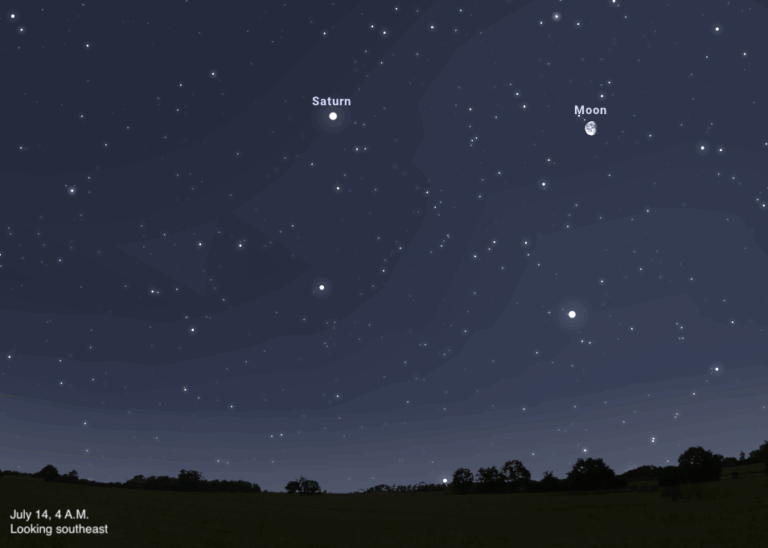

Venus and Saturn meet in late November’s predawn sky. Brilliant Venus shines more than 60 times brighter than its neighbor. Astronomy: Roen Kelly

The first features you’ll notice are two parallel dark belts on either side of a brighter zone centered on the giant’s equator. Under steady observing conditions, a series of alternating belts and zones comes into view. Storms appear as more-subtle dark features, spots, festoons, or plumes, especially near the edges of the twin equatorial belts. Also look for the faint pinkish glow of the centuries-old megastorm known as the Great Red Spot.

Jupiter’s other claim to observational fame is its collection of four bright moons. Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto orbit the planet with periods ranging from 1.8 days (Io) to 16.7 days (Callisto). Their differing speeds cause their relative positions to change significantly from night to night and, in many cases, from hour to hour.

But the most exciting events occur when one of the moons or its shadow (or both) crosses Jupiter’s face. As Jupiter approaches opposition in December, the Sun, Earth, and Jupiter align more closely, so satellite transits follow closer on the heels of their corresponding shadow transits.

Io nicely illustrates this effect. The innermost major moon transits Jupiter both November 7 and 30. On the 7th, Io’s shadow touches the planet’s eastern limb at 10:11 p.m. EST, and the disk trails 38 minutes behind. Both take about 130 minutes to cross the jovian disk. On the 30th, Io’s shadow starts its journey at 10:22 p.m. EST, followed by its disk only four minutes later. Because the shadow is dark and the planet’s cloud tops relatively bright, the shadow shows up best.

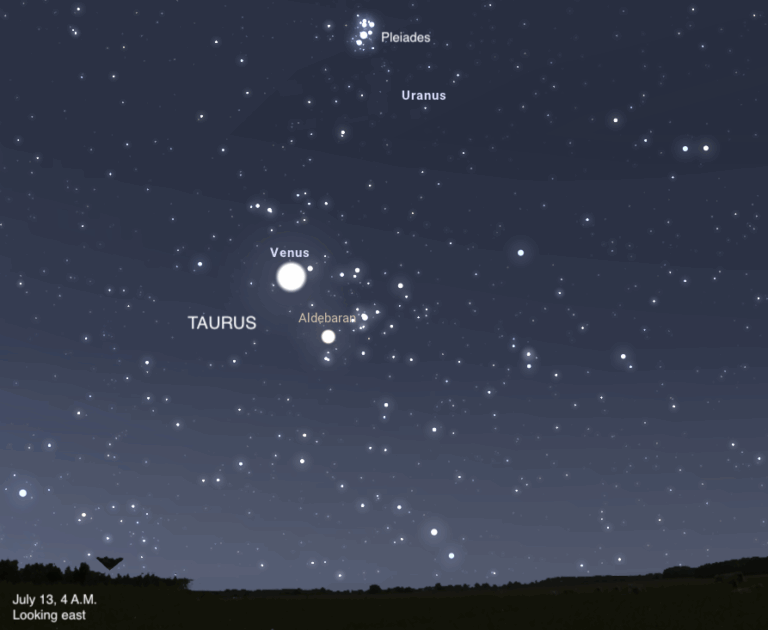

As Jupiter starts to descend in the west before dawn, shift your gaze (at least temporarily) to the eastern sky. Venus will draw your attention immediately. The brilliant object shines at magnitude –3.9, some three times brighter than Jupiter.

Venus rises about two minutes later each morning. Part of this comes about because the planet’s angular distance from the Sun decreases from 35° to 28° during November; the rest results from the Sun rising later as winter approaches.

A total solar eclipse occurs over northern Australia after sunrise November 14. Look for Baily’s beads (the bright spots at upper right) just before totality begins or after it ends. Tunc Tezel

Meanwhile, Saturn pulls away from the Sun. On the 1st, it lies just 6° away and remains lost in the solar glare. By month’s end, its elongation stands at 32° and the planet rises nearly three hours before the Sun. As you might guess, Venus and Saturn are destined to pass near each other late this month.

The two meet in eastern Virgo on November 26 and 27. On the 26th, Venus lies 0.8° west of Saturn; the following morning, Venus appears 0.7° south of its neighbor. At magnitude 0.7, Saturn appears barely 1 percent as bright as Venus.

On both mornings, a telescope at low power shows the two in the same field of view. Venus displays a 12″-diameter disk and a fat gibbous phase. Saturn’s globe measures 16″ across while the magnificent rings span 35″ and tilt 18° to our line of sight. Because both objects lie on the far side of the solar system from our perspective, their telescopic appearance changes little during November.

In the month’s final week, Mercury leaps into view in morning twilight. On November 24, it rises about an hour before the Sun and climbs 7° high in the east-southeast 30 minutes later. You may need binoculars to spot the 1st-magnitude object against the twilight sky. By month’s end, Mercury rises 100 minutes before our star and appears 7° high an hour before sunrise.

Use Venus as a guide — it appears to Mercury’s upper right and about twice as high. The innermost planet has brightened substantially, to magnitude –0.2, and shows up easily to naked eyes. A telescope reveals a disk 8″ in diameter that’s slightly less than half-lit.

November’s biggest astronomical event occurs during daylight. Shortly after sunrise November 14, residents and visitors who trek to northern Australia will see the New Moon slide in front of the Sun and create a total solar eclipse. On the centerline north of Cairns, Queensland, observers will witness 2 minutes and 5 seconds of totality. For complete details on viewing this eclipse, see the article in December’s Astronomy.

Two weeks after the solar eclipse, on November 28, the Full Moon passes through Earth’s shadow. Although the Moon never enters the dark umbral shadow, more than 90 percent of our satellite dips into the lighter penumbral shadow. Observers should see the northern half of the Moon darken slightly around the middle of this lunar eclipse (at 14h34m UT). People in Australia, eastern Asia, and the Pacific islands have the best views of the event. Those across much of North America can see the eclipse’s early stages, which begin at 12h15m UT (7:15 a.m. EST).

The Leonid meteor shower peaks before dawn November 17. Observers under dark skies could see up to 20 meteors per hour, and perhaps a few fireballs like this one from 2001. Tony Hallas

The Lion comes alive in mid-November

Great meteor watching typically requires a clear, dark sky paired with a reliable shower that peaks when the Moon is out of the way. This month, nature provides the shower and Moon-free conditions. If the weather cooperates, observers at dark sites could be in for quite a show.

The Leonid meteor shower should peak around 4:30 a.m. EST November 17. The three-day-old waxing crescent Moon sets in early evening, which leaves the prime viewing hours after midnight unencumbered by moonlight. Astronomers expect the shower to produce 15 to 20 meteors per hour shortly before dawn. That’s when the radiant — the point in the constellation Leo the Lion from which all the meteors appear to emanate — reaches its highest altitude. (For details about the Leonids, see “Observe the Leonid meteor shower” on page 58.)

Aristoteles and Protagoras stand out on a waning gibbous Moon. This scene closely matches what observers will see the night of November 3/4. Consolidated Lunar Atlas/UA/LPL

A surprising delight visible under new light

Most lunar observers study their favorite target during its waxing phase, before Full Moon as the Sun rises over our satellite’s nearside. It makes sense — after all, a waxing Luna appears in the evening sky while a waning Luna rises in late evening or after midnight. But craters, ridges, and valleys look different near sunset than they do under their traditional sunrise illumination on a waxing Moon.

The waning gibbous Moon rises late on the evening of November 3. The region along the terminator — the dividing line between lunar day and night — should appear oddly unfamiliar through a telescope. The first feature to catch your eye will be the snaking Serpentine Ridge in the eastern part of Mare Serenitatis. The ridge’s relationship to the entire Sea of Serenity is easy to see on the waning Moon.

If you sweep about halfway to the north pole from there, you’ll land on the large and detailed crater Aristoteles. The low Sun angle transforms its apron of impact splatter into an expanse of roughness whose texture is as fine as the night and your telescope will allow. Check out the shadow that cuts across its middle — a huge “divot” of light appears on what normally would be a smooth curve. The divot traces back to a small crater that breaches Aristoteles’ western flank and allows sunlight to reach the floor.

Farther northwest, the crater Protagoras mars the lava-filled basin of Mare Frigoris. It almost resembles a hole in a golf course putting green. When the Sun sets over a normal crater, the western flank of its raised rim glows brightly. But an ancient lava flow came right up to the western lip of Protagoras, so there’s no rim. Under the more familiar lighting conditions of a waxing Moon the evening of November 20, you might never suspect that the unusual is hiding in plain sight.

| When to view the planets | ||

| EVENING SKY | MIDNIGHT | MORNING SKY |

| Mars (southwest) | Jupiter (southeast) | Mercury (southeast) |

| Uranus (southeast) | Uranus (southwest) | Venus (southeast) |

| Neptune (south) | Jupiter (west) | |

| Saturn (east) | ||

Comet C/2011 F1 (LINEAR) should glow around 10th magnitude during early November, when it lies low in the west after sunset. Astronomy: Roen Kelly

A comet invades the Serpent-bearer’s lair

Unless an unexpectedly bright visitor arrives from the depths of the solar system, November’s best comet puts on a brief show in the early evening sky. You’ll need to search for Comet C/2011 F1 (LINEAR) during November’s first 15 days, when it hangs low in the west as the sky grows dark.

The comet then appears about 5° above the horizon. Because the small diffuse object glows only at 9th or 10th magnitude and its light has to pass through thick layers of our atmosphere, you’ll need an 8-inch or larger telescope to spy this interplanetary wanderer. Also, plan to observe from a dark site that has a flat and unobstructed western horizon. Try a range of magnifications to find the sweet spot between the comet’s surface brightness and the background sky’s darkness.

Fortunately, several modestly bright stars lie near LINEAR’s path to help guide you to the right area. The comet travels parallel to a series of bright stars at the southern end of the sprawling constellation Ophiuchus the Serpent-bearer, the brightest of which is 3rd-magnitude Zeta (ζ) Ophiuchi. But first, LINEAR cuts across the northern edge of Scorpius the Scorpion, where it slides 3′ south of 5th-magnitude 16 Scorpii on November 4. And on the 15th, it skirts less than 0.5° north of the globular star cluster M107.

After midmonth, this small ball of ice and dust disappears in the Sun’s glow. By the time it emerges out of the glare in February, it lies deep in the southern sky and only Southern Hemisphere observers will be able to glimpse it. Luckily, Comet C/2012 K5 (LINEAR) will take its place for northern observers during December.

Asteroid Ceres lurks in western Gemini this month, passing near 3rd-magnitude Eta (η) Gem and the 5th-magnitude star cluster M35. Astronomy: Roen Kelly

Touching the feet of the celestial Twins

Asteroid 1 Ceres glides through western Gemini in November, passing less than 1° south of the splashy star cluster M35 after midmonth. If you wait until midevening to observe, Gemini appears high enough in the east to clear most surrounding houses and trees. The biggest asteroid brightens from magnitude 8.0 to 7.3 this month, bringing it within reach of small telescopes and even steadily held binoculars.

Ceres easily outshines the background stars in this part of the winter Milky Way. It’s a walk in the park to locate the space rock during November’s first 10 nights: Center your scope on the 3rd-magnitude red giant Eta (η) Geminorum, and Ceres will be the next brightest point in the field. The two objects appear closest (3′ apart) on the 4th.

Over the following nights, the 590-mile-wide asteroid gradually approaches the rich star cluster M35. Although you’ll need a wide-angle eyepiece to frame them nicely in the same telescopic field of view, they will appear as a pretty couplet through any binoculars. Only one of M35’s distant suns matches the asteroid’s brightness.

Astronomers eagerly anticipate their first close-up views of Ceres from the Dawn spacecraft, which is scheduled to arrive in February 2015. Dawn recently left asteroid 4 Vesta, which it had been orbiting since July 2011. (By the way, Vesta currently lies in Taurus, some 10° west-southwest of Ceres’ position.)

Martin Ratcliffe provides professional planetarium development for Sky-Skan, Inc. Alister Ling is a meterologist for Environment Canada.