Still, Saturn and Mars remain standouts. The ringed planet lies high in the south as darkness falls, offering superb views to anyone with a telescope. And the Red Planet remains a beacon. Although it has lost some of its summer luster, Mars shines brightly and looms large through telescopes.

The Sun’s advance brings the two outer planets to center stage. Neptune stands high in the late evening sky and shows up nicely with optical aid. Meanwhile, Uranus reaches opposition and peak visibility in late October, giving us our best views of this ice giant in more than a half-century.

But we’ll start our tour of the night sky in evening twilight with the most difficult target of all. Mercury hangs just above the southwestern horizon after sunset during October’s final week. Perhaps your best chance to spot it comes on the 27th, when it lies directly below brilliant Jupiter. Use binoculars to locate the giant planet, which lies 6° high a half-hour after sunset, and you should see Mercury 3.4° (about half a field of view) beneath it. The inner planet shines at magnitude –0.2, one-quarter as bright as Jupiter.

Mercury’s poor visibility arises in part from solar system geometry. On October evenings, the ecliptic — the apparent path of the Sun across our sky that the planets follow closely — makes a shallow angle to the western horizon from mid-northern latitudes. So Mercury’s elongation from the Sun translates mostly into distance along the horizon and not into altitude.

The same geometry affects Venus, with the planet’s location south of the ecliptic further compromising our view. From 40° north latitude on the 1st, Venus stands 2° high 30 minutes after sunset. It gleams at magnitude –4.7, however, so you should see it if you have an unobstructed horizon. A telescope shows the planet’s 47″-diameter disk and slender crescent phase.

Jupiter proves to be an easier target. The outer world lies 14° to Venus’ upper left October 1, and it stands 10° high in the southwest an hour after sundown. Shining at magnitude –1.8, it shows up well against the darkening sky.

The giant planet loses about 3° of altitude each week. This leaves only a narrow window for observing it through a telescope, with the best conditions coming early in the month when it lies relatively high. The gas giant’s disk spans 33″ on the 1st and shows a pair of dark atmospheric belts.

Early evening views of Saturn should be spectacular. The magnitude 0.5 planet stands about 25° high in the south as darkness starts to fall in early October, and it doesn’t set until 11 p.m. local daylight time. The ringed world shifts into the southwestern sky after sunset as the month progresses, but it doesn’t lose much altitude.

Although a naked-eye view of Saturn is impressive, any optical aid will blow you away. Binocular views from under a dark sky reveal the planet set against the rich backdrop of the Milky Way in Sagittarius.

But Saturn always looks best through a telescope. Even the smallest scope shows the planet’s stunning ring system encircling a yellowish globe. In mid-October, the gas giant’s disk measures 16″ across while the rings span 37″ and tip 27° to our line of sight. This large tilt gives us a dramatic view of the ring system’s structure. The most obvious feature is the Cassini Division, a dark gap that separates the outer A ring from the brighter, broader B ring.

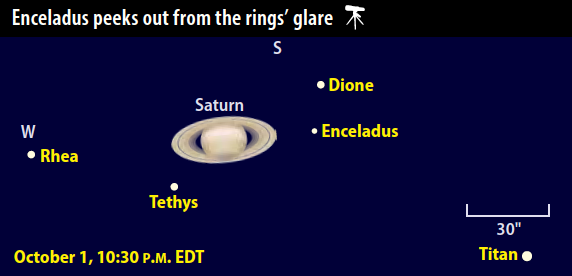

Small telescopes also reveal several moons. Titan glows at 8th magnitude and shows up through any instrument. It orbits the planet once every 15.9 days, passing south of the planet October 7 and 23 and north of it October 15 and 31.

Fainter still is Enceladus. You’ll likely need an 8-inch instrument to see this 12th-magnitude moon, which revolves around Saturn once every 1.4 days. The rings’ glare masks this inner satellite unless it lies near greatest eastern or western elongation. North American observers should hunt for Enceladus on October 1, when it lies farthest east of Saturn (14″ from the rings’ edge) and 17″ north of Dione.

Look to the south after darkness falls, and Mars meets your gaze. Although the Red Planet reached opposition in late July, it remains dazzling against the background stars of Capricornus. Mars shines at magnitude –1.3 as October opens and loses about half its luster by month’s end, when it glows at magnitude –0.6. Still, this is brighter than any star visible on October evenings.

Mars crosses the breadth of Capricornus during October. It starts the month in the constellation’s southwestern corner, and appears nearly 30° high at its peak around 9 p.m. local daylight time. By late October, the planet lies in northeastern Capricornus and stands 5° higher when it peaks around 8 p.m.

With Mars placed high in the south in early evening, observers with telescopes should be in for a treat. Although the planet’s apparent diameter shrinks from 16″ to 12″ during October, that’s still big enough to show some surface features. And that might be an improvement over the opposition view. A dust storm that began in late May blew up in June, filling the planet’s atmosphere with dust and obscuring the surface. As of mid-July, it looked like the global storm would continue through opposition.

Assuming clear martian skies, North American observers will see the following features near the center of the planet’s gibbous disk on October evenings. Mare Cimmerium should be the most prominent feature at the beginning of the month, with Mare Sirenum taking over at the end of the first week. Solis Lacus appears front and center in mid-October, while Sinus Meridiani and Sinus Sabaeus take center stage during the month’s third week. The planet’s two most prominent features — the bright Hellas Basin and the dark Syrtis Major — appear best on October’s final few evenings.

Neptune lies between the 4th-magnitude stars Lambda (λ) and Phi (ϕ) Aquarii. In early October, it’s midway between these two. The planet’s westward motion during the month carries it closer to Lambda, and on the 31st it stands 2.1° east of this star. A telescope reveals Neptune’s 2.3″-diameter disk and subtle blue-gray color.

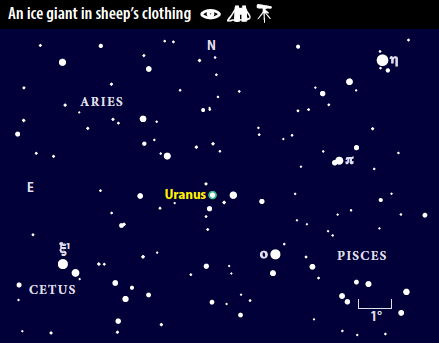

Uranus reaches opposition October 23. It then lies opposite the Sun in our sky, so it rises at sunset and remains visible all night. It also comes closest to Earth at opposition and thus glows brightest. But an outer planet’s appearance changes slowly, and Uranus sustains its magnitude 5.7 peak all month.

The ice giant glows brightly enough to spot with the naked eye, but binoculars make the task much easier. (That’s particularly true the night of opposition, when the Full Moon lies nearby.) Look for Uranus in southwestern Aries, just over the border from Pisces. In the nights around opposition, you can find it 2.8° northeast of 4th-magnitude Omicron (ο) Piscium.

The view of Uranus through a telescope should be superb because it lies so high in our sky. From 40° north latitude on the night of opposition, the planet climbs 61° above the southern horizon at its peak around 1 a.m. local daylight time. This is the highest it has appeared at opposition since February 1962. Even small scopes show a distinctive blue-green disk that spans 3.7″.

Full Moon arrives October 24, a day after Uranus reaches opposition. But don’t be surprised to see a nearly Full Moon hanging low in the east after sunset for a few days around this date. The so-called Hunter’s Moon rises only about 30 minutes later each night compared with an average of 50 minutes. This shorter-than-normal delay arises because the ecliptic makes a shallow angle to the eastern horizon around sunset on autumn evenings.

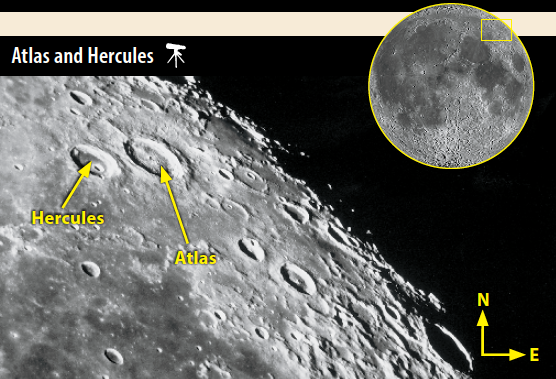

The Sun sets on two mythical strongmen

The Hunter’s Moon effect allows early evening observers a chance to see our satellite under reverse illumination. In the nights after Luna reaches its Full phase October 24, the waning gibbous Moon rises only about 30 minutes later each evening, compared with a more typical delay of 50 minutes.

This gives viewers a nice chance to see sunset illumination on the Moon without staying up late. And just as the play of light and shadows looks different at sunrise and sunset in your own neighborhood, the Moon appears different under reversed lighting.

Target the Moon’s northeastern quadrant through your telescope as night falls October 26. You’ll quickly see a pair of nice craters named after brawny legends from Greek mythology: Atlas and Hercules. Hercules spans 43 miles and shows a dark, lava-flooded floor punctuated by a sharp-edged crater. Atlas measures 54 miles across and lies closer to the Moon’s limb. This older crater has a wrinkled floor and a jumble of central peaks. As the Sun sets over this area on the 27th, the mountain peaks disappear into darkness shortly before Hercules’ inner crater succumbs to the shadows.

Under “normal” lighting on a waxing crescent Moon, the two craters emerge into sunlight with all the shadows reversed. Sunlight illuminates their outer rims on the east and their inner crater walls on the west. The small crater inside Hercules is lost in shadow October 13, but shows up easily on the 14th.

The Orionids are usually October’s top meteor shower. And that may well be the case in 2018. Although the shower peaks under a waxing gibbous Moon on October 21, our satellite sets around 4 a.m. local daylight time. That leaves two hours of darkness until twilight begins. Observers could see up to 20 meteors per hour radiating from Orion the Hunter.

But the Draconids could give the Orionids a run for their money. This typically minor shower might erupt the night of October 8/9 because its parent comet — 21P/Giacobini-Zinner — passed closest to the Sun last month. (See “Catch a comet crossing the Milky Way” on p. 42.) Previous outbursts have followed the comet’s return. Viewers could see 10 or more meteors per hour coming from Draco the Dragon in the hours before midnight.

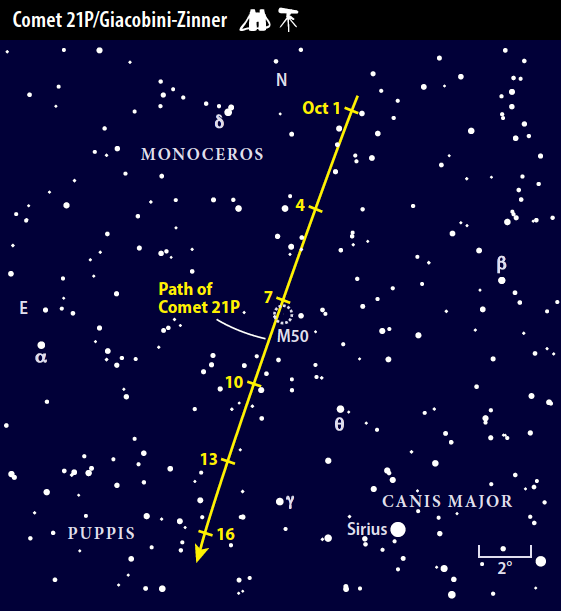

Observers don’t often get a chance to see a reasonably bright comet and a meteor shower at the same time, but it’s truly rare to set eyes on the very body producing those streaks of light. Such an opportunity presents itself during October’s first half, when Comet 21P/Giacobini-Zinner graces the morning sky while the Draconid meteor shower reaches its peak. (See “Will the Hunter slay the Dragon?” on p. 37 for details on the Draconids.)

Comet Giacobini-Zinner should glow at 8th magnitude in early October. Observers can then find it plunging southward through the winter Milky Way, passing from Monoceros into Canis Major. Because this is only a few weeks after the comet made its closest approach to both the Sun and Earth, astronomers expect it to sport a nice gas tail about 1° long.

The Draconid meteor shower peaks the night of October 8/9, coinciding with Earth’s passage through the comet’s orbital plane. It’s worth following Giacobini-Zinner in the days before, during, and after this crossing. Thanks to our changing perspective, the gas tail initially looks like a blue ribbon. It then turns edge-on as we pass through the orbital plane, and then flattens out again when we view it from the other side.

Astroimagers will have many chances this month to capture 21P floating in front of the pretty fields and star clusters of the winter Milky Way. The finest pairing occurs the morning of October 7, when the comet lies just north of open cluster M50.

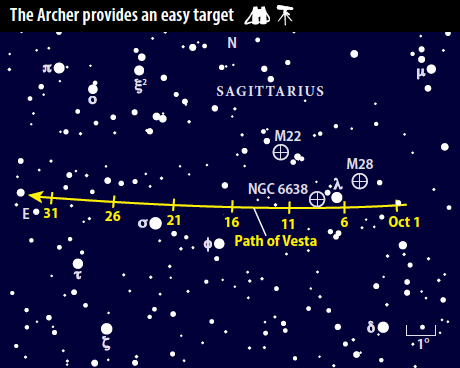

The brightest minor planet couldn’t be much easier to find early this month. If you can tear yourself away from Saturn, just drop 4° southeast to magnitude 2.8 Lambda (λ) Sagittarii, the star that marks the lid of the Teapot asterism in Sagittarius the Archer.

On October 1, Vesta lies 2.1° due west of Lambda and just 4′ south of a magnitude 6.5 field star. The asteroid glows a magnitude fainter. Identifying Vesta becomes easier as it heads eastward during the next week. From the 5th to the 9th, the space rock lies within 1° of Lambda, passing 20′ south of the orange giant star the evening of the 7th.

Continuing eastward, Vesta slides within 1° of magnitude 2.1 Sigma (σ) Sgr in the Teapot’s handle from October 21–24. During these four evenings, the asteroid is the brightest object to the north of this bluish star. Closest approach occurs on the 23rd, when 40′ separate the two.

Throughout October, Vesta travels at a pace of nearly 1′ per hour. This is fast enough that you can notice its movement in one observing session, particularly when it passes near one of the field stars mentioned earlier.

The Teapot also boasts a few bright globular star clusters near Vesta’s path that are worth exploring. Both 7th-magnitude M28 and 9th-magnitude NGC 6638 lie within 1° of Vesta during October’s first 10 days, and 5th-magnitude M22 lies 2° north of the asteroid during the month’s second week.