Key Takeaways:

- The article presents the North Celestial Pole (NCP) region as an underappreciated astronomical observation area for Northern Hemisphere astronomers, noting its consistent visibility regardless of season.

- Key celestial objects discussed within Ursa Minor include Polaris (α Ursae Minoris), a 2nd magnitude multiple-star system approximately 1° from the NCP; NGC 3172 (Polarissima Borealis), a 15th magnitude lenticular galaxy identified as the closest galaxy to the celestial pole; and Lambda (λ) Ursae Minoris, a red giant whose historical and future alignment with the NCP is influenced by Earth's precession.

- In Cepheus, the discussed objects are the galactic pair NGC 2276 and NGC 2300 (Arp 114); NGC 188 (Caldwell 1), characterized as the Milky Way's oldest and northernmost open cluster; and NGC 40 (Bow-Tie Nebula), which is the northernmost planetary nebula.

- Camelopardalis is highlighted for IC 512, a 12th magnitude, nearly face-on intermediate spiral galaxy exhibiting a compact nucleus and faint S-shaped arms.

Every community has a tourist attraction everyone knows about but locals never visit. Perhaps it’s because it’s always there and can be seen anytime. And yet “anytime” often ends up translating to “very rarely” or “never” and we find ourselves admitting “I’ve been meaning to go there” without ever making the effort.

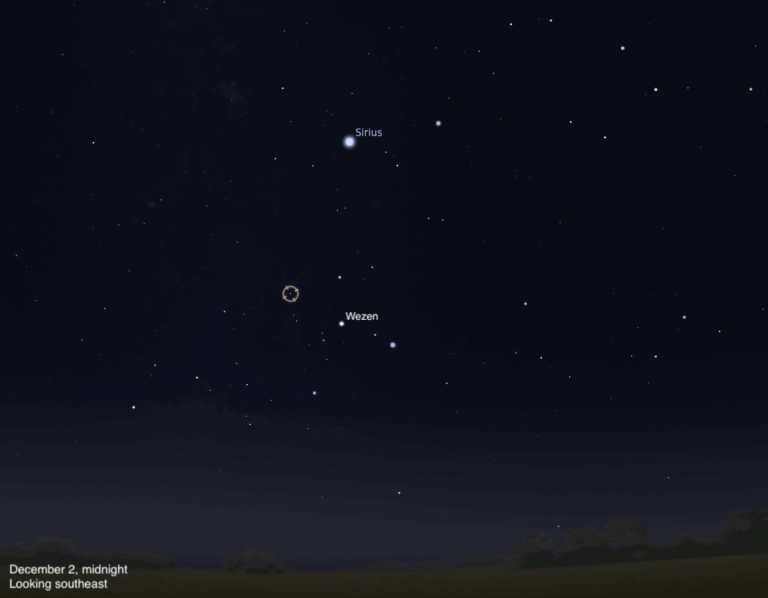

The night sky has one of these places: the North Celestial Pole. Except for observers using Polaris to align a telescope to track celestial objects, this region doesn’t garner much interest. There are no Magellanic clouds or Milky Way, and no bright and shiny deep-sky objects to attract the eye. The rich star fields of Cassiopeia and the expansive areas of bright galaxies in Ursa Major are more appealing.

Yet just like your local tourist attraction, the north polar skies are always visible for Northern Hemisphere observers, no matter the season. The same objects can be seen at any time of year, not requiring you to suffer under hot, humid summer skies or on frigid winter nights.

Now — or on the next fair-weather night of your choosing — is the time to stop meaning to go there and visit this region of the sky. So, welcome one and all! I’m Alan, your star-crossed tour guide. Let me tell you about some wonders near the North Celestial Pole, featuring objects in three northern constellations: Ursa Minor, Cepheus, and Camelopardalis.

Ursa Minor

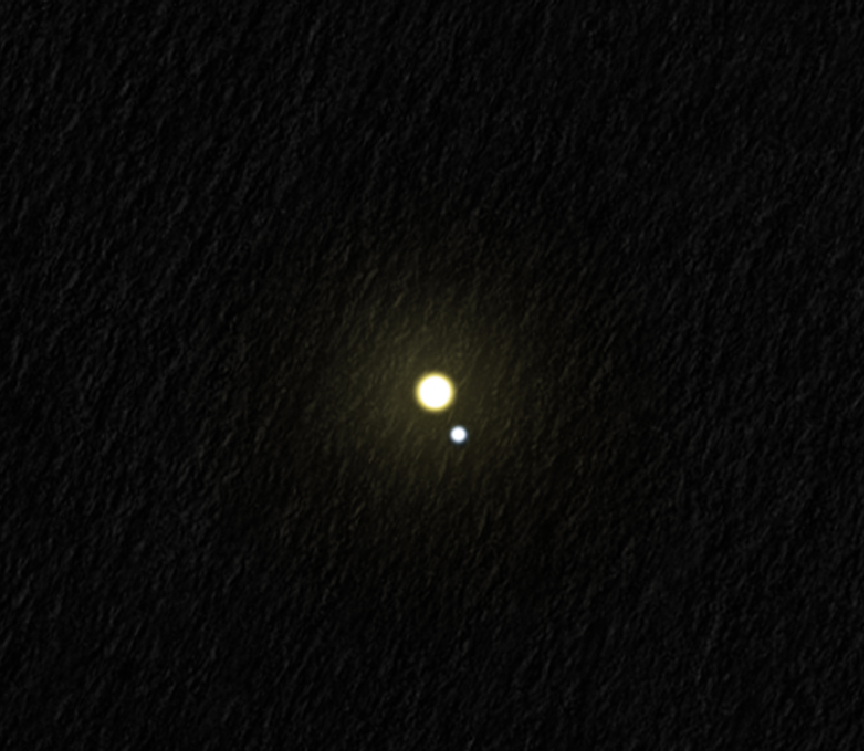

The brightest object on our tour is Polaris (Alpha [α] Ursae Minoris). A multiple-star system, it lies less than 1° from the North Celestial Pole and shines at 2nd magnitude. At 447 light-years in distance, the light you see tonight left around the time La Paz, Bolivia, was founded in 1548. Polaris is a triple system: The primary, Polaris Aa, is a Cepheid variable with a close companion (Polaris Ab) that orbits once every 291/2 years. Its second companion, Polaris B, shines at magnitude 8.7 some 18″ from the primary star. Steady skies and temperature-acclimated optics will make Polaris A and B easier to split.

As Earth’s axis wobbles, Polaris will eventually wander away from the celestial pole and fainter stars will become the Pole Star, as is the case today at the South Celestial Pole, which has no bright star nearby. Don’t worry, folks — this will not be a problem for another few thousand years.

Slightly farther from the North Celestial Pole is our first classic deep-sky object: galaxy NGC 3172. Discovered by John Herschel in 1831, this faint fuzzy is named Polarissma Borealis because of its proximity to the celestial pole. A galaxy around 15th magnitude rarely attracts deep-sky observers because these are the dandelions of the sky — they’re everywhere! But one galaxy has to be the closest to true north, and NGC 3172 is that galaxy. Our polar dandelion is small, about 1′ in diameter. It is classified as a lenticular galaxy, with a disk dominated by older stars and lacking extensive resources (hydrogen and helium) to form new stars. Yet two supernovae have been observed within it, in 2010 and 2017, indicating it is still creating some stars, just not in vast numbers. This galaxy lies some 285 million light-years beyond Polaris. An 11-inch telescope under skies free from light pollution should reveal it. If you want to see its neighbor 1.7′ to the west-southwest, PGC 36268, you will need an 18-inch scope.

For something more colorful in an otherwise bland region, look for Lambda (λ) Ursae Minoris. At magnitude 6.4, this red giant is visible to observers with excellent vision, located between Polaris and Delta (δ) UMi, the next star in the handle of the Little Dipper. The red color is visible in small optics. Astronomer James Kaler noted on his STARS website that, due to Earth’s 26,000-year processional wobble, Lambda was closer to the North Celestial Pole than Polaris several hundred years ago and the pole will fall between the two stars around 2060. A double star, Lambda’s companion is 14th magnitude and 55″ away. However, with no detailed observations in the last century (even professional astronomers avoid this landmark, it seems!), Kaler added it could simply be a faint background star.

Cepheus

Moving into the King’s domain, NGC 2276 and NGC 2300 may be my favorite objects in the north polar region. NGC 2276 by itself is also designated No. 25 in Halton Arp’s 1966 Atlas of Peculiar Galaxies, while both galaxies together are cataloged as Arp 114. The apparent proximity of the spiral NGC 2276 to the lenticular galaxy NGC 2300 led Arp to classify the pair as interacting. Redshift data indicate these galaxies today have a separation of some 23 million light-years — far greater than the Milky Way and Andromeda. NGC 2300 is closer, at 90 million light-years away, while NGC 2276 is 113 light-years distant.

NGC 2276 is an asymmetrical pinwheel-type spiral similar to M101. It is classified as an early-type spiral (Sa–Sc), with its distorted arms attributed to gravitational interaction with NGC 2300 and a tidal tail visible at radio wavelengths caused by pressure from the surrounding hot intergalactic gas. Both galaxies glow around 11th magnitude; NGC 2276 is slightly fainter. NGC 2300 is slightly larger, 3.2′ by 2.8′, while NGC 2276 is 2.6′ by 2.3′. Observing this pair requires modest optics — a 6-inch scope works fine.

NGC 188 is the northernmost open cluster in our sky. Discovered by John Herschel in 1831, it is 5° from the North Celestial Pole. Far from the galactic plane, its isolation has kept the cluster’s members from wandering away. Its estimated age is 6.8 billion years, significantly older than our Sun’s 4.6 billion years. At a distance of 5,400 light-years, the group’s apparent diameter of 15′ translates to about 20 light-years across. The loose conglomeration of about 100 stars can be seen through an 8-inch scope. Use low power to get a feel for its shape and density. See if higher magnification can pick up star colors. It is known to contain blue stragglers — older stars that appear much younger (bluer, and thus hotter), which astronomers believe are formed when two stars merge either via collision or accretion to create a single younger-looking star with a new source of fuel.

The northernmost planetary nebula is the southernmost object featured on this list. NGC 40 in Cepheus lies 18° from the North Celestial Pole. Discovered by William Herschel in 1788, it’s magnitude 11.5 and 36″ in diameter, with a conspicuous magnitude 11.6 central star. It is sometimes called the Bow-Tie Nebula, but perhaps the Parentheses Nebula might be more apropos — in large telescopes, the partial ring structure visually resembles a parentheses around the star.

Camelopardalis

Located in the constellation of the Giraffe, spiral galaxy IC 512 is comparable in size to NGC 2300, but about a magnitude fainter at 12th magnitude. First recorded in 1890 by the British astronomer William Denning, this nearly face-on spiral has a compact nucleus and S-shaped arms that are likely too faint for visual detection even in large instruments. Classified as an intermediate spiral (SABc), it shows an elongated hub and weak arms (comparable to the Pinwheel Galaxy [M33] in Triangulum) in photos. A telescope with moderate aperture (8 to 11 inches) will show this galaxy as a slightly oval glow with a bright center.

Far from the rich Milky Way star fields, the northernmost part of the sky awaits your discovery. This list is merely to get you started — there are many more galaxies and plenty of faint double stars to be seen.

Spend some time in this region and then you can truly claim: “Been there, done that!”