Key Takeaways:

The winter Milky Way flows to the east of brilliant Sirius and Canis Major through a region of our southern sky filled with faint stars. Once, those faint stars formed the constellation Argo Navis, the mighty mythical ship that carried Jason and the Argonauts as they searched for the Golden Fleece on the eastern shores of the Black Sea in present-day Georgia. Or so the story went.

To commemorate those adventures, Ptolemy immortalized the ship as one of the original 48 constellations in his work, the Almagest. Like the ship, the constellation was huge, covering almost 1,700 square degrees, or 4 percent of the entire sky.

Because of this unwieldiness, the 18th-century astronomer Nicolas Louis de Lacaille divided Argo into three parts, which we still recognize and use today: Puppis the Poop Deck or stern; Carina the Keel or body; and Vela the Sails.

This month, we will set sail for Puppis, a small region of the late winter Milky Way that is rich in buried binocular treasure.

First, to zero in on Puppis, focus your attention on Canis Major. If Sirius is a jewel or tag on the Big Dog’s collar, the profile of its head curves northeastward using the 4th-magnitude stars Iota (ι), Gamma (γ), and Theta (θ) Canis Majoris. Depending on local conditions, you might need to use your binoculars to see them.

Pause at Gamma, and place it at the western edge of your field of view through your binoculars. Then glance just a bit farther east. You’ll first see a knot of 6th- to 8th-magnitude stars bunched together. That’s open cluster M47.

Of the 50 stars that make up M47, I can count up to 11 through my 10x50s. Four form a fuzzy-looking “Y” asterism in the middle of the cluster. That cloudiness is just due to the low magnification, however. It clears up when I examine the cluster with my 16x70s.

You’re bound to notice an orange 5th-magnitude star set about 40′ west of M47. That’s the variable star KQ Puppis. Although they probably have no affiliation with each other (some studies suggest they may), the color contrast between it and M47 is eye-catching. Defocusing your binoculars slightly will enhance the color.

KQ Puppis is actually a binary system, made up of a red supergiant star and a blue-white main sequence star. Like many similar red supergiants, KQ fluctuates slightly in brightness, causing the overall magnitude to change between 4.82 and 5.17.

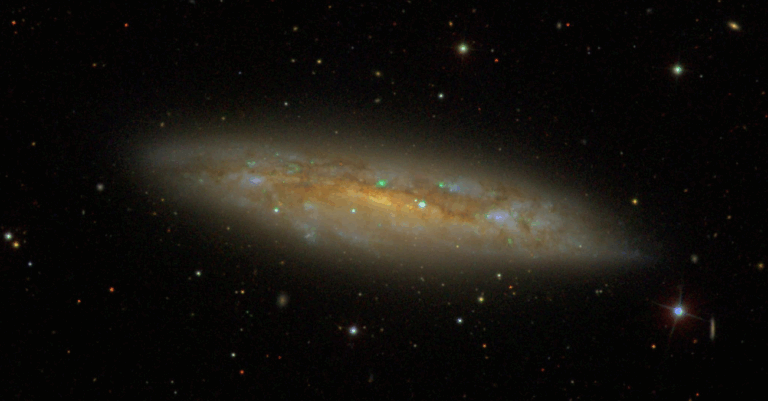

Open cluster M46 lies just over a degree east of M47, so it easily fits into the same field of view. In reality, they are nowhere near each other in space. M47 is estimated to lie 1,600 light-years away, while M46 is much more distant at 5,400 light-years.

Like snowflakes and fingerprints, no two open star clusters are exactly the same. I can’t think of anywhere in the sky where this is better illustrated than with M46 and M47. While M47 is a young pup of a cluster, only 78 million years old, the 500 stars that make up M46 are about 300 million years old.

Even though M46 is much richer in stars than M47, the greater distance veils their individuality through binoculars. Most of us will see M46 as a soft, amorphous glow suspended in a starry field. If you own 70mm or larger binoculars and have good sky conditions and a pretty good eye, you just may be able to spy a few faint points peeking out through the glow. The brightest star in M46 shines at 9th magnitude, but most hover below 11th magnitude.

Images of M46 show that it is being photo-bombed by a celestial interloper, planetary nebula NGC 2438. The planetary shines faintly at about 10th magnitude, so again it is just within reach of some giant binoculars. The problem in convincingly seeing the planetary is twofold. Not only is it dim, but it’s also tiny. That’s this month’s challenge: Can you spot NGC 2438 through binoculars? Please email me your results.

Incidentally, NGC 2438 is not inside M46. It is actually much closer, “only” about 2,900 light-years from Earth. Thinking spatially, it’s actually closer to M47 than to M46.

We all have favorite binocular objects. I’d enjoy hearing about yours, and possibly feature them in future columns. Contact me through my website, philharrington.net.

Until next month, remember that two eyes are better than one.