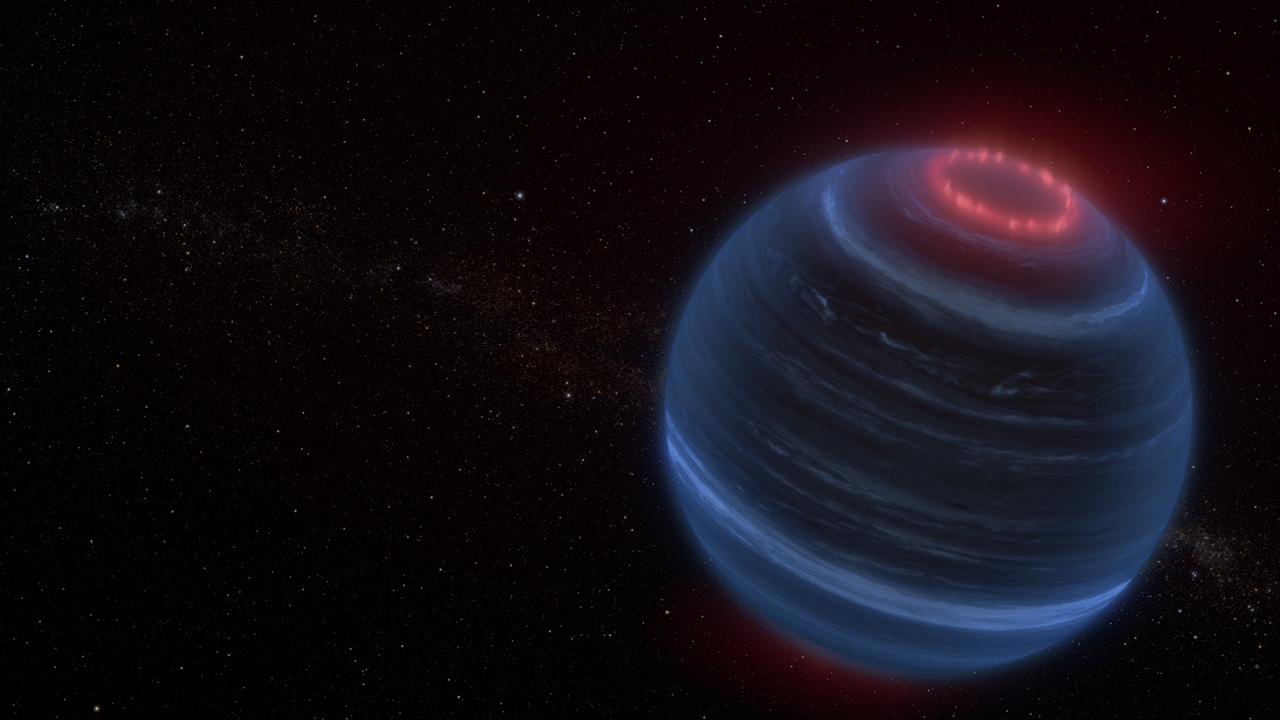

Some 855 light-years away resides an exoplanet with a water cycle vastly different than our own.

The exoplanet, WASP-121 b, belongs to a class of planets known as hot Jupiters. These gas giants circle their stars with much tighter orbits than our own Jupiter orbits the Sun. Where Jupiter takes 12 Earth years to complete one trip around the Sun, WASP-121 b’s year takes just 30 hours.

WASP-121 b is also tidally locked to its host star, meaning only one side of the world faces its star, while the other is cast in perpetual darkness. As a result, the upper atmosphere on the daytime side of WASP-121 b gets as hot as 5,400 degrees Fahrenheit (3,000 degrees Celsius). This causes water molecules on the exoplanet to break down into their atomic components: hydrogen and oxygen.

And the nightside isn’t that much cooler, however, dropping only to about 2,700 F (1,500 C).

Nevertheless, this stark temperature difference between the two hemispheres has a sweeping impact on WASP-121 b. Horizontal winds blow across the entire planet from west to east. This pulls the hydrogen and oxygen from the dayside to the nightside. There, the disrupted water molecules can reform, becoming water vapor. But this is only temporary, as the winds blow the vapor back to the dayside, restarting the cycle.

These observations, laid out in a paper published in Nature Astronomy Feb. 21, is the first-time researchers have tracked a complete water cycle on an exoplanet.

Metal clouds and liquid gems

Though water clouds can never form on WASP-121 b, the planet is not devoid of rain. But it’s not the same type of rain we are familiar with on Earth. Instead, clouds of iron, magnesium, chromium, and vanadium fill the night sky — where temperatures are cold enough for metals to condense into clouds.

But these metal clouds don’t last for long. As the winds carry them alongside the water vapor back to the dayside, they again evaporate.

Metal clouds may not be the strangest aspect of WASP-121 b, either. Researchers were stumped to find that metals like aluminum and titanium were not among the elements detected in the upper atmosphere of the exoplanet, as might be expected. One likely explanation is that these metals reside deeper in the atmosphere, and thus are invisible to observations.

If that is the case, then it’s possible that the aluminum combines with oxygen to form corundum. When mixed with impurities like chromium, iron, titanium, or vanadium, this compound becomes rubies or sapphires on Earth.

So, WASP-121 b may see liquid gems raining on its nightside.