Mercury switches from the evening to morning sky this month, while the giant planets dominate the night. The moons of Jupiter and Saturn offer many events. Venus stars on early November mornings, but drops lower day by day.

Mercury shines at magnitude –0.1 on Nov. 1 and hangs low in the southwest after sunset. It lies in Scorpius and makes a nice addition to the claws of the Scorpion on that date, 1° from 2nd-magnitude Delta (δ) Scorpii. The pair is 4° high in the southwest 30 minutes after sunset, and dips below the horizon by 7 p.m. local daylight time.

By Nov. 9, Mercury fades to magnitude 0.3 and stands level with Antares, lying 4° to the star’s right. With the change to standard time on the 2nd, sunset occurs around 4:50 p.m. local time; 30 minutes later Antares and its planetary companion sit 2.5° above the southwestern horizon. Mercury is now at its best for Southern Hemisphere observers.

On Nov. 12, Mars stands 1.3° due north of Mercury. Mars is dim, at magnitude 1.4, but Mercury is only magnitude 0.8. Use magnitude 1.1 Antares as your guide, which should be easily spotted with binoculars in bright twilight. Mercury stands 5° to the right (northwest) of Antares, and Mars is positioned at roughly the one o’clock position relative to Mercury. Begin looking west about 25 minutes after sunset, when Antares is 3° high. You’ll have about 10 minutes to find Mercury and Mars — quite a challenge. Good luck.

Within a few days Mercury drops from view as it moves toward a Nov. 20 solar conjunction. It reappears in the morning sky in the last few days of the month. We’ll revisit it later.

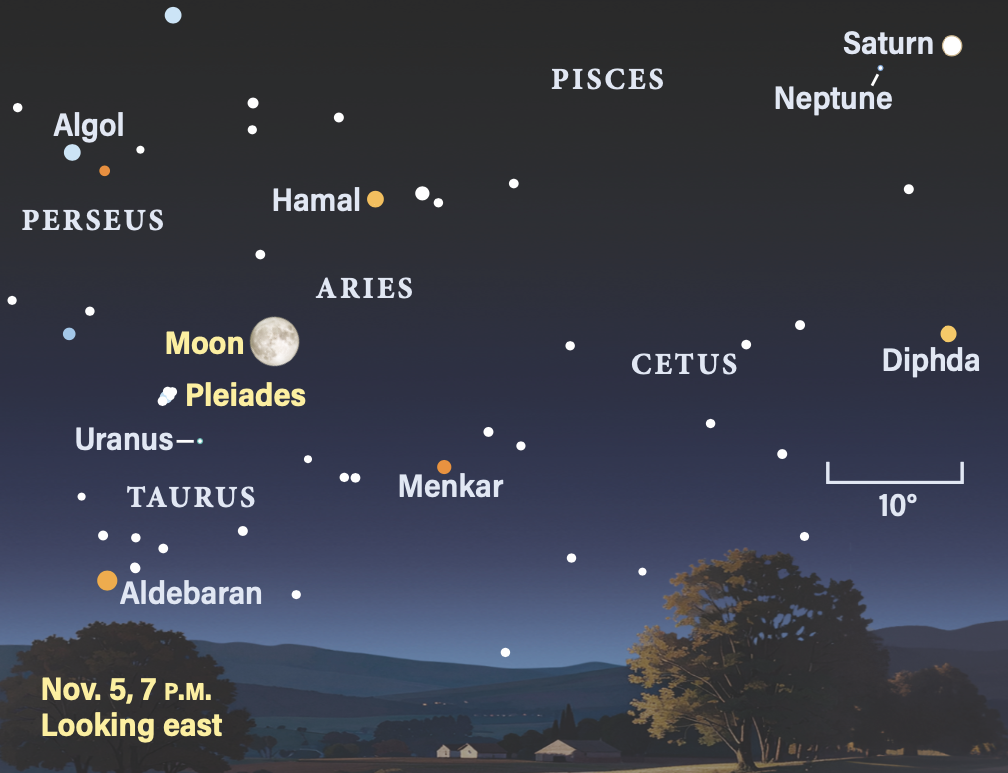

Saturn is in the northeastern corner of Aquarius as November begins. It stands high in the southeast once the sky is dark and remains visible all night, setting around 2 a.m. local time midmonth. A nearly Full Moon passes Saturn on Nov. 2, moving 4° due north of the planet after it has set for the U.S.

Saturn starts November at magnitude 0.8 and dips 0.1 magnitude by month’s end. The tilt of the rings declines to a minimum of 0.4° before slowly starting to increase. They require larger amateur scopes and good seeing to spot. The long axis spans 42″ by midmonth.

Titan continues its series of transits. Look closely with a telescope the evening of Nov. 6 as darkness falls. Titan is already transiting the disk above the very fine, almost edge-on rings. It’s midway across the disk at 6:50 p.m. EST and continues until just before 9:30 p.m. EST, when it begins a 16-minute-long egress.

Observers with large scopes recording high-speed video might also spot the shadow of Rhea as Titan approaches the western limb. The tiny, 10th-magnitude moon is impossible to see visually against to the brilliant disk, but check your video for it. Rhea exits the disk around 10:18 p.m. EST and lies only 2.5″ southeast of Titan. An hour later, Rhea is due south of Titan and they are less than 2″ apart, blending together visually.

On the 14th, Titan reappears from behind Saturn’s disk beginning at 7:26 p.m. EST (in twilight for the Mountain time zone). It can take a few minutes for Titan to become noticeable — watch the southeastern limb below the rings for a growing dimple as the moon reveals itself.

Nov. 22 sees Titan once more crossing Saturn. Now it’s midway across the disk shortly after 5 p.m. EST, some two hours earlier than on Nov. 6. The 16-minute egress begins around 7:50 p.m. EST.

Titan once again reappears from behind Saturn on Nov. 30, beginning at 6 p.m. EST, taking some 15 minutes to fully appear.

Tenth-magnitude Tethys, Dione, and Rhea all orbit Saturn closer than Titan. Watch these moons for close conjunctions. For example, Dione and Rhea stand 0.8″ apart at 9 p.m. EST Nov. 17, with the pair 28″ west of Saturn. The next night, you’ll see Dione and Tethys merge around 8:25 p.m. EST, as the former nearly occults the latter 22″ west of Saturn.

Enceladus is faint (12th magnitude), but it’s a great time to view it, with the rings so dim. It remains within about 37″ of Saturn, or about 15″ beyond the edge of the rings.

Iapetus reaches western elongation Nov. 16, with its icy face pointing earthward. You’ll find the 10th-magnitude moon 10′ west of Saturn. Note there is an 11th-magnitude star 15′ west of the planet, as it may be easy to confuse the two.

Neptune stands about 4° northeast of Saturn and requires binoculars to spot. Scan for a string of three 4th- and 5th-magnitude stars northeast of Saturn, then continue about the same distance again to find the magnitude 7.7 planet. It is 2° due north of 27 Piscium, the southeasternmost and brightest of the three stars, on the 18th. A waxing gibbous Moon passes 3° north of Neptune on the 29th.

Neptune is 2.7 billion miles from Earth and spans a mere 2″. Through a telescope it appears nonstellar with a bluish hue. It’s best viewed in the early evening, when Neptune and Saturn stand highest in the southern sky.

Uranus is in Taurus and reaches opposition Nov. 21. Finding the planet is easy: Using binoculars, scan 4.3° south of M45, the Pleiades, to find a pair of 6th-magnitude stars 20′ apart. Uranus begins the month 1.7° east of the easternmost star (14 Tauri). By Nov. 30, Uranus stands only 30′ east of this star. Through a telescope, Uranus reveals a pale greenish disk 4″ wide. On Nov. 5, the Full Moon rises some 10° west of M45.

Jupiter rises about 11 p.m. local daylight time on Nov. 1 and shines at magnitude –2.3. It brightens to –2.5 by the 30th. It lies 6.5° south of Pollux in Gemini on the 1st. Jupiter’s easterly path reverses on the 11th, beginning its retrograde motion. A waning gibbous Moon stands north of Jupiter on Nov. 9/10.

Jupiter’s cloud features are a treat to follow. The two dark belts straddling the equator pop easily into view. Finer details come with patience, especially as Jupiter’s altitude climbs. It reaches 35° high around local midnight midmonth, and by 4 a.m. it’s over 60° high in the south. Its fast rotation causes atmospheric features to move noticeably across the disk in 10 to 15 minutes.

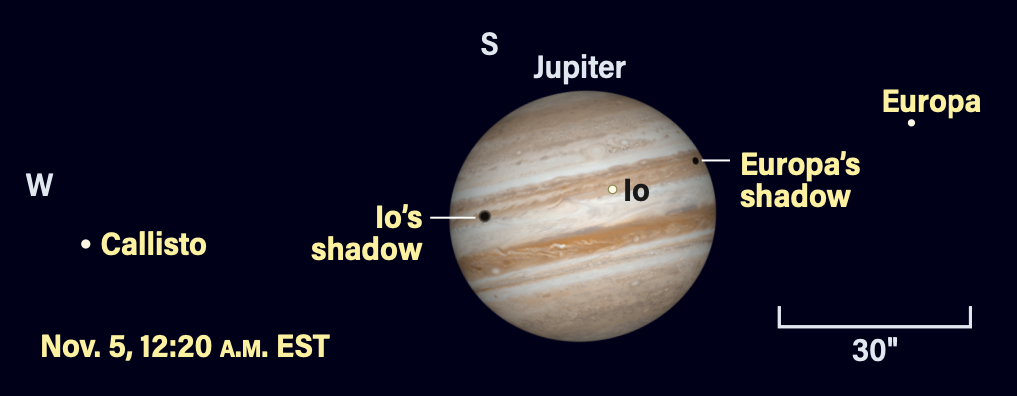

The four Galilean moons are visible through any telescope and even in tripod-mounted binoculars. They orbit Jupiter every two to 17 days.

On Nov. 3/4, Callisto casts its shadow onto Jupiter’s southern polar region. The dark bite appears at the southeastern limb around 2:06 a.m. EST on the 4th. The shadow is fully visible some 10 minutes later and takes a little over three hours to traverse Jupiter. This event repeats on the evening of the 20th, when the eastern half of the U.S. sees Callisto’s shadow leave the disk a few hours after Jupiter rises. Io also transits on the same evening, exiting just before midnight EST. Some hours later, early on Nov. 21, Callisto begins to transit at 5:53 a.m. EST.

A series of Ganymede transits occurs this month. On the 17th, East Coast viewers see the transit begin soon after Jupiter rises. Observers farther west see Ganymede in midtransit as the planet rises. Ganymede leaves Jupiter’s southwestern limb at 12:55 a.m. EST (the 18th in this time zone only). Timing is difficult because the western limb of Jupiter is partly in darkness (the planet is 99.3 percent lit).

This repeats Nov. 24/25 with Ganymede’s shadow transiting as Jupiter rises, ending at 12:23 a.m. EST (the 25th in this time zone only). Ganymede’s transit begins at 1:13 a.m. EST and ends at 4:30 a.m. EST.

Two shadows and a moon transit Jupiter’s disk Nov. 4/5. Europa’s shadow begins to transit at 12:12 a.m. EST (again, the 5th in EST only), with Io and its shadow already transiting. Io’s shadow leaves at 12:32 a.m. EST, giving a 20-minute window when all three are visible.

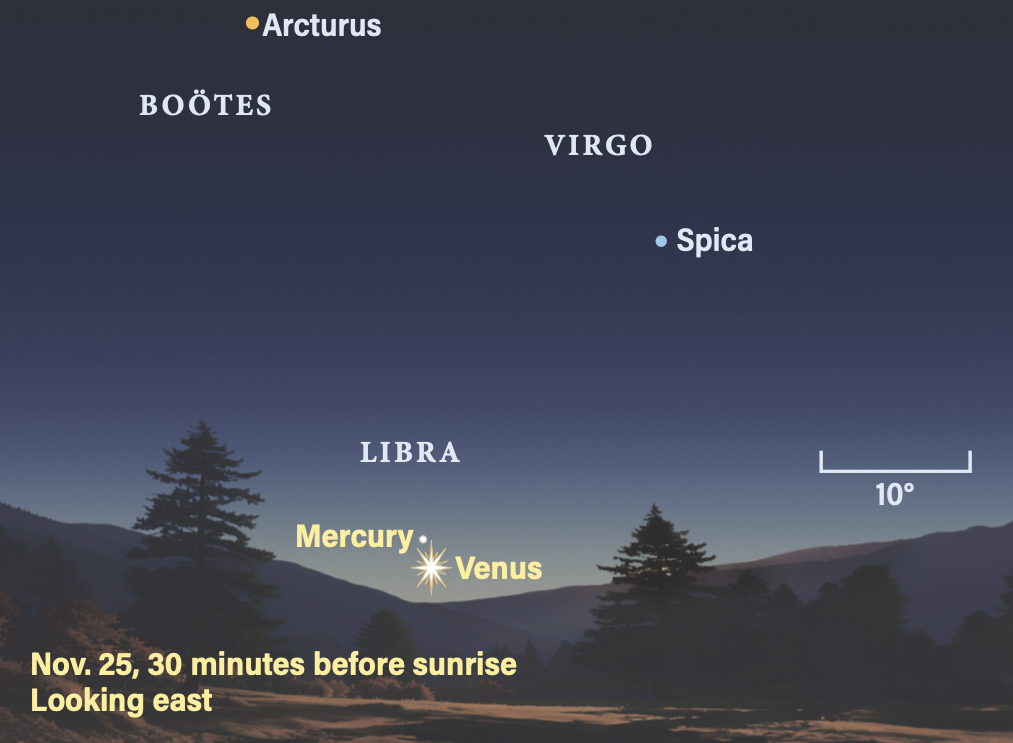

Venus stands less than 4° north of Spica, Virgo’s alpha star, on Nov. 1. Magnitude 1.0 Spica is hard to spot in morning twilight, but Venus dazzles at magnitude –3.9. Binoculars will show the star to its south. Venus rises by 6:15 a.m. local daylight time on the 1st, about 75 minutes before sunrise.

The planet’s visibility declines throughout the month. For example, on the 1st, Venus is 4° high in the east at 6:30 a.m. local daylight time — this is about an hour before sunrise. By the 7th, at 5:30 a.m. local time (now an hour before sunrise, thanks to the end of daylight saving time) Venus has dropped to 1° high. A telescopic view will show an almost-full disk (97 percent lit) spanning 10″ on this date.

By Nov. 20, Venus still rises an hour before sunrise; 20 minutes later, around 6:15 a.m., it’s obvious, standing 3° high. Now start watching closely each morning, because dim Mercury joins the scene, coming out of solar conjunction. On the 24th, Venus and Mercury are separated by 1.5°, although Mercury requires binoculars to spot at magnitude 2.9. Things improve the next day, when Mercury brightens to magnitude 2.1, standing 1.4° from Venus.

As Venus continues to sink, Mercury’s visibility improves. The tiny planet reaches magnitude 0.2 and rises at 5:30 a.m. local time on the 30th, standing 5° high in the eastern sky an hour before sunrise.

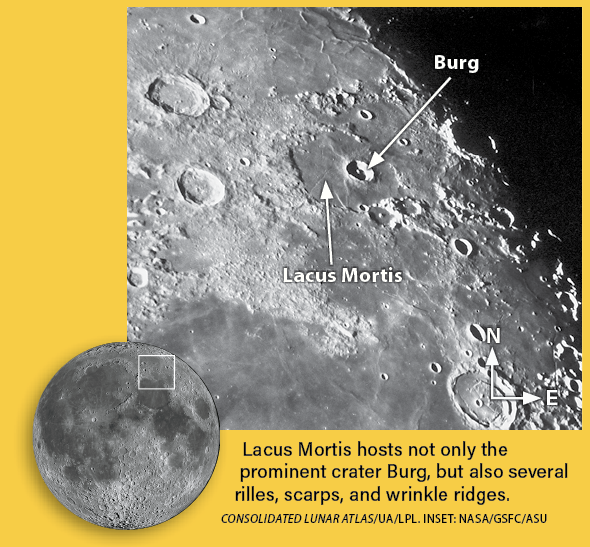

Rising Moon: At death’s door

Lurching across the Lake of Death is best done in the late evening. On Nov. 9, the lunar night is about to overtake Lacus Mortis and the prominent crater Burg for two weeks. Take advantage of the season’s earlier sunsets and longer nights to observe the Moon past Full phase. Shining from the west instead of the east, the low Sun literally puts the terrain in a different light.

Our eyes provide the brain with 3D depth cues to subconsciously judge height from the length of shadows. Lacus Mortis has very little remaining of its eastern wall, but the rather jumbled block of higher ground to the west on the sunward side casts a nice shadow. That rough texture is the sum of numerous episodes of spray or ejecta from various previous impacts all overlaying each other. The upwelling of lava through the floor of Lacus Mortis provided a clean slate for future hits.

Burg is a modestly sized, relatively young crater with a classic sharp raised rim and a single central peak. With a diameter of 25 miles, it is big enough that its inner walls have slumped down to form a relatively simple terrace. The pair of similarly sized craters on the south rim of Lacus Mortis show signs of advanced age: Their rims have been battered down by long-term bombardment.

After rigor mortis froze the lava plain into place, the Moon continued to heave and subside underneath, leaving a fascinating set of fractures. Rimae Burg is a rille (channel) heading off to the southwest, formed when the terrain pulled apart. The scarp to the south came into being as the ground to the west dropped down. Immediately east of the scarp is another rille. Heading to the north is a wrinkle ridge, a raised line where the surface was pushed together.

Re-examine these features when sunrise returns to this strip of the Moon on the evening of the 25th. By then Luna will be a five-day-old, wide crescent, resplendent as always with its magnificent stretch of features along the terminator.

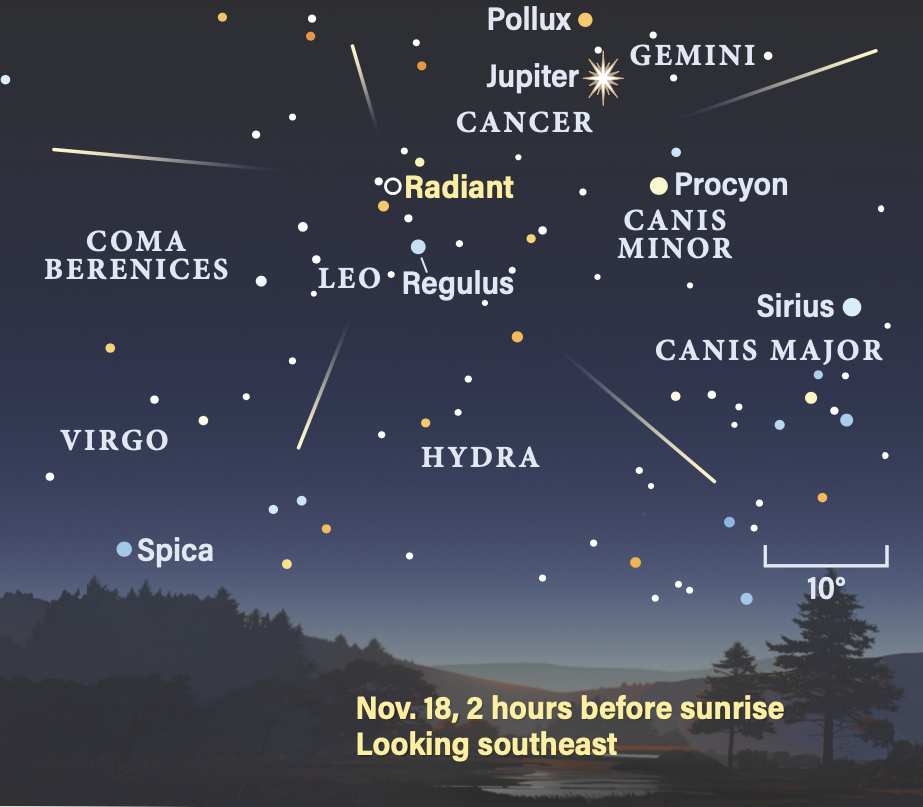

Meteor Watch: Look for long trains

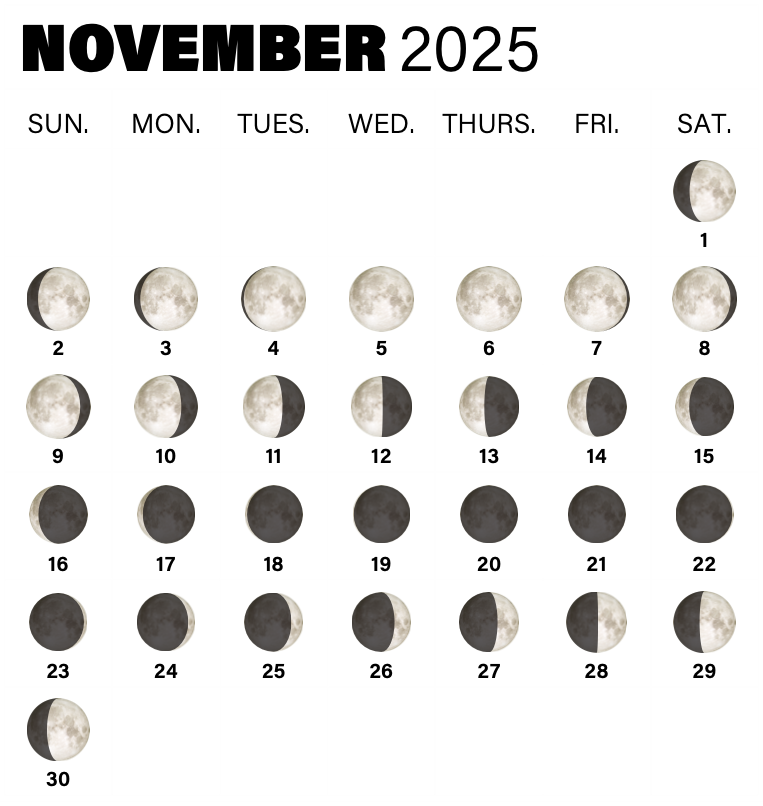

This year’s annual Leonid meteor shower peaks Nov. 17/18 during nighttime across the U.S. and coincides with a crescent Moon that doesn’t rise until 5:30 a.m. local time. This shower is associated with Comet 55P/Tempel-Tuttle, which last reached perihelion in 1998. In recent years hourly rates have been declining. However, with so much planetary action going on, it’s a great time to add in meteor observing.

Leo rises around local midnight and the radiant, located in the Sickle, is visible through dawn, when it reaches 70° altitude in the south. The hour before morning twilight is best for observing, placing us on the leading hemisphere of Earth as it flies into the stream of debris. The Leonids are swift and many meteors leave glowing, persistent trains. Look 40° to 60° away from Leo to spot the longer trails.

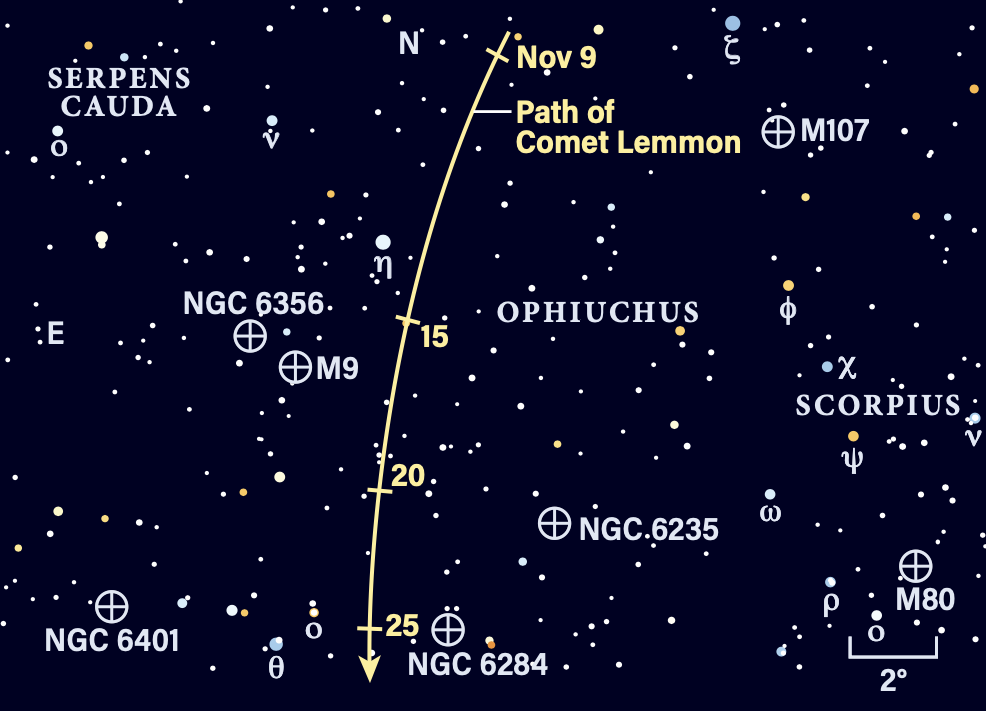

Comet Search: Pairs of puffballs

To collect twice the cometary reward, be onsite in the country with your scope aimed into Ophiuchus as the sky darkens. The soft glow of C/2025 A6 (Lemmon) loses contrast as it travels through more atmosphere, sinking into the western horizon. A 4-inch scope will show the bright globular clusters M10 and M12 as you swing up to the fainter C/2024 E1 (Wierzchoś), arcing past M14.

The window opens on the 9th, when the Moon doesn’t rise for another hour. Lemmon is expected to be at its brightest (8th magnitude) some 46.5 million miles from the Sun, then fade gradually as its distance increases. Two weeks later it disappears into the sunset as Wierzchoś reaches 9th magnitude. Medium magnification offers better overall contrast, but going higher gives a view of the false nucleus and reveals which flank has the sharper bow shock facing the Sun.

Another 8th-magnitude comet, 210P/Christensen, greets astronomers already out in the country who can awaken two hours before sunrise in November’s last week.

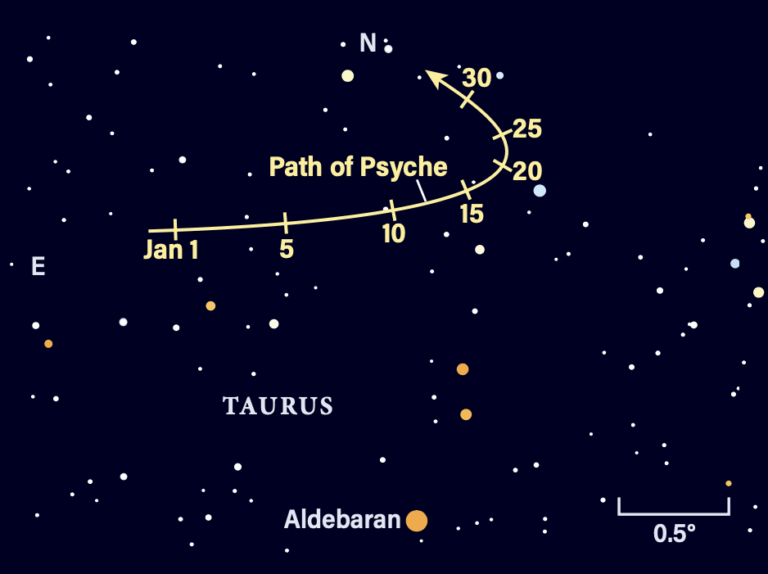

Locating Asteroids: Sometimes easy, other times not

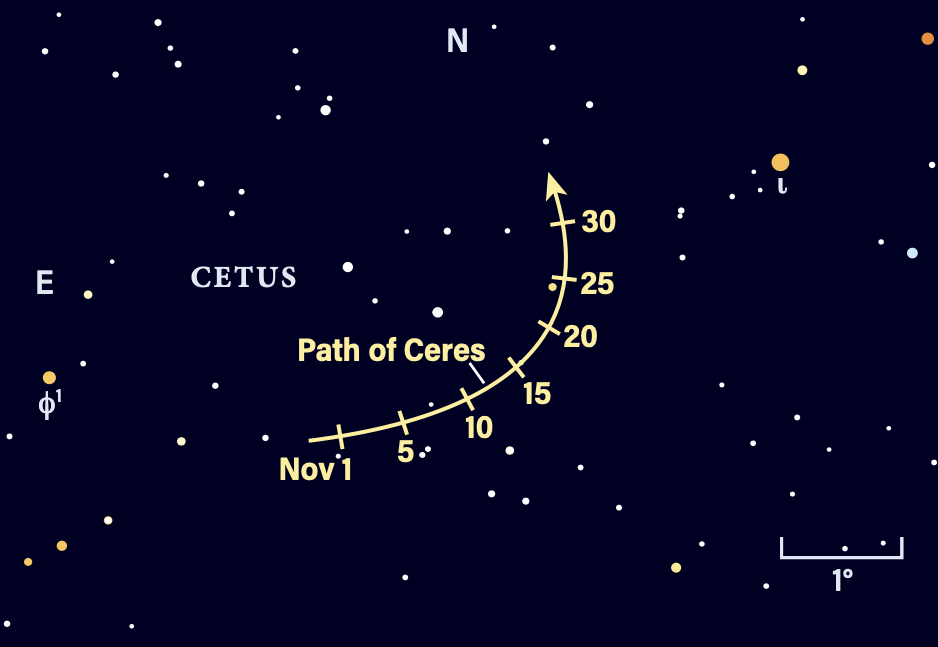

Glowing at a respectable 8th magnitude, the ruler of the asteroid belt, 1 Ceres, can slide incognito through the sparse star fields of Cetus, only to become quickly recognizable when attended by nearby stellar courtesans. Before launching on a search, let the first nights of November pass to sidestep the Moon’s bright veil.

When you use a go-to drive, you might land ½° away. Is that 8th-magnitude dot an asteroid or a background star? For star-hoppers, start at Iota (ι) Ceti, halfway between Saturn and the bright magnitude 2 star Beta (β) Ceti closer to the southeast horizon. Shift east along a daisy chain to arrive at Ceres. Either way, move past the spot to confirm that other stars come into view. From the 6th to the 8th, the dwarf planet lies north of an 8th-magnitude pair of wide cat’s eyes. On the 15th it approaches the wide double star HD 2447 and leaves it the next night.

Discovered on Jan. 1, 1801, by Giuseppe Piazzi, Ceres was orbited by the Dawn spacecraft from 2015 to 2018.

Star Dome

The map below portrays the sky as seen near 35° north latitude. Located inside the border are the cardinal directions and their intermediate points. To find stars, hold the map overhead and orient it so one of the labels matches the direction you’re facing. The stars above the map’s horizon now match what’s in the sky.

The all-sky map shows how the sky looks at:

10 p.m. November 1

8 p.m. November 15

7 p.m. November 30

Planets are shown at midmonth