Key Takeaways:

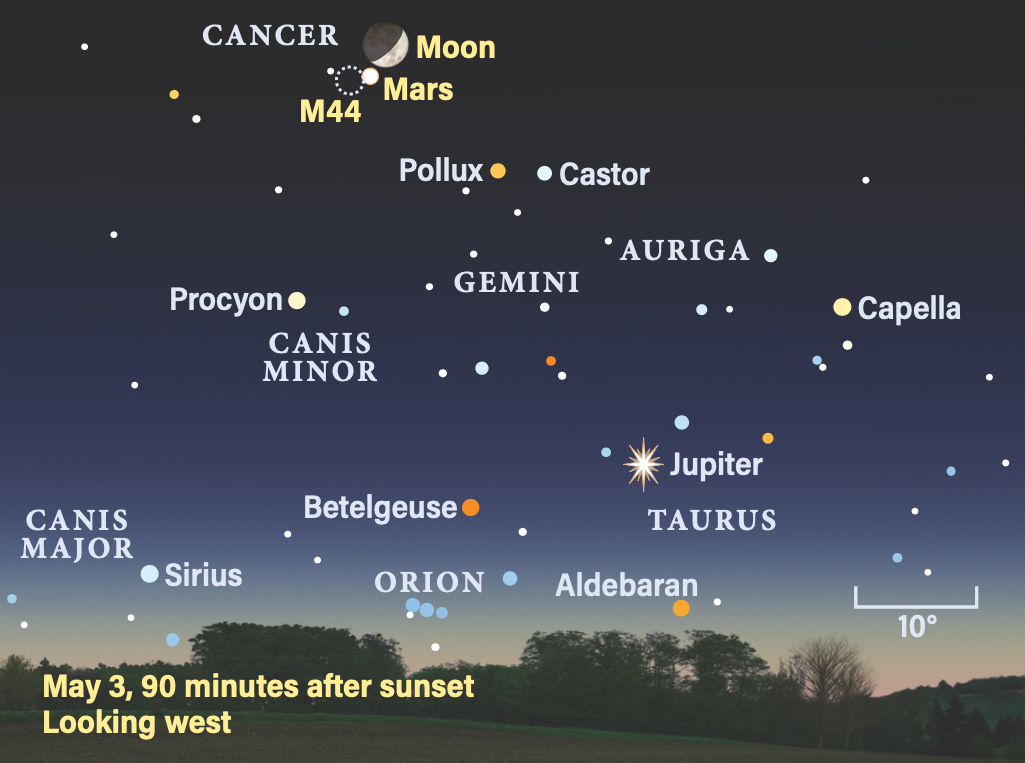

Jupiter and Mars are on display during May evenings. It’s your last chance to grab a good view of Jupiter before it drops out of sight for midsummer. A gathering of planets in the morning sky offers some nice opportunities, and in the first week of May they’re joined by meteors from the annual Eta Aquariid shower.

Let’s begin our tour with Jupiter, continuing its long goodbye as its elongation from the Sun diminishes from 40° to 18°. It sets just after 11 p.m. local daylight time on May 1st and around 9:30 p.m., or about an hour after sunset, on May 31. Your finest views occur in the first few days of the month, when the planet spans 34″ and remains above 20° altitude an hour after sunset.

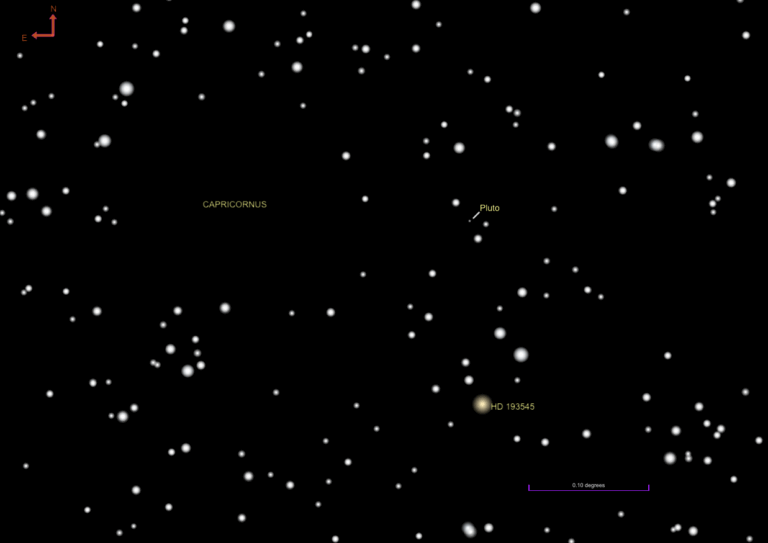

Jupiter shines at magnitude –2.0 in early May and lies in Taurus the Bull. It appears in the western sky along with Orion, Gemini, and Auriga. On May 18, it stands 2° due north of Zeta (ζ) Tauri, with the faint Crab nebula (M1) 1.3° southwest of the planet, although twilight will render the nebula invisible.

Jupiter is magnificent when viewed through a telescope in twilight. This is because the glare of the planet is diminished. Delicate atmospheric details — such as the dark equatorial belts and more temperate-latitude dark belts, bright zones, and plumes — span the disk. The apparent diameter of Jupiter shrinks to 32″ by the end of the month.

By May 7th, the planet falls below 20° an hour after sunset and becomes more difficult to observe, particularly if you have obstructions to the west. The narrowing observing window nonetheless provides some interesting events involving the Galilean moons. Io performs a transit with its shadow on May 4. Io reaches Jupiter’s eastern limb at 9:06 p.m. EDT, its shadow following at 9:54 p.m. EDT. From the Central time zone west, the transit is already underway in twilight.

The following evening, May 5, watch Europa disappear behind the western limb of Jupiter at 10 p.m. CDT. This event is best viewed in the western U.S. — Jupiter is getting very low (less than 10° high) for Midwest observers and has already set for those along the Eastern Seaboard.

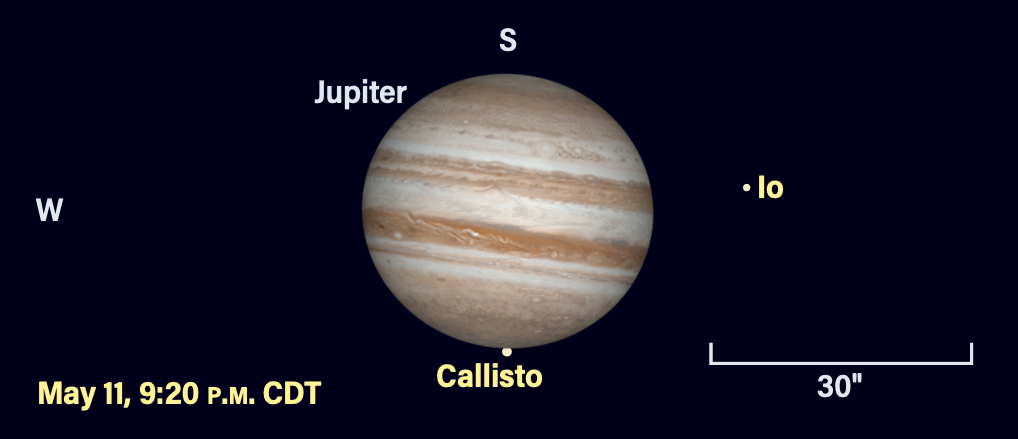

The orbital plane of the Galilean moons is tilted such that Callisto misses any occultations or transits, but this month Callisto slides very close to the northern pole of Jupiter. Watch this unusual event on the evening of May 11. The closest point, where the edge of Callisto is predicted to graze the northern edge of Jupiter, occurs around 9:20 p.m. CDT. Watch all evening as the fascinating encounter plays out. Also watch Io begin a transit at 9:07 p.m. MDT (Jupiter is now very low in the Central time zone), just minutes before Ganymede reappears off the planet’s northeastern limb from within Jupiter’s shadow.

Europa performs a nice transit followed by its shadow on May 14, beginning at 8:12 p.m. EDT. The shadow appears as Europa reaches the central meridian of Jupiter, at 9:30 p.m. EDT. The western half of the country sees Europa exit the disk at 8:52 p.m. MDT, while its shadow is near the middle of the disk. Galilean satellite events in late May become difficult to observe as Jupiter dips below most observers’ tree line in the late evening.

Mars provides a lovely addition to Cancer the Crab as May opens, shining at 1st magnitude. It stands within 2° of M44, the Beehive star cluster, and the scene is best viewed in binoculars.

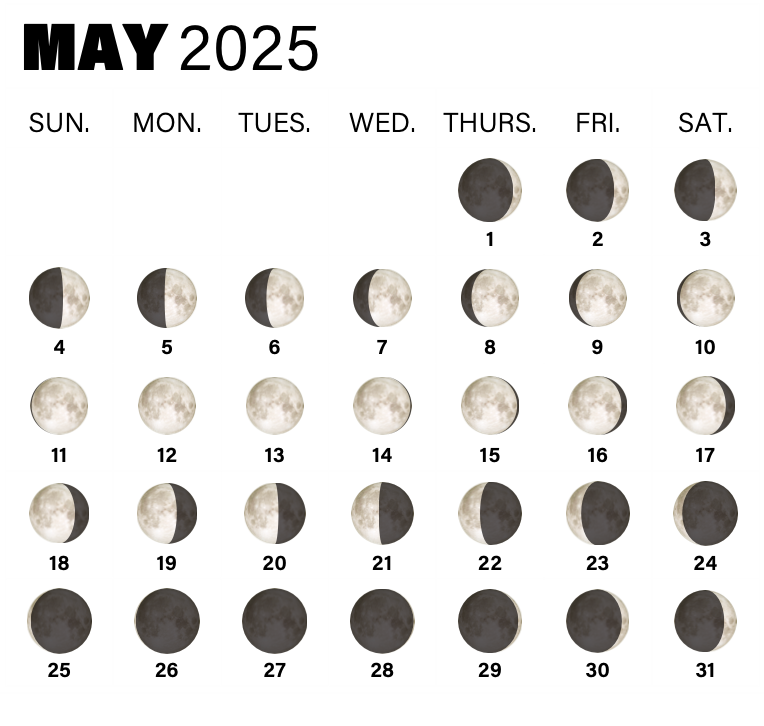

Two days later, on the 3rd, a waxing crescent Moon joins Mars. Our satellite passes within 2° of the planet, which is now skirting the outer limits of M44. The next evening, Mars is 40′ due north of the center of the Beehive, a stunning pairing in binoculars or low-power telescope eyepiece.

During the rest of May, Mars continues across eastern Cancer and moves into Leo on the 25th. By the 31st, Mars stands 9° northwest of Regulus, Leo’s brightest star. It remains visible until roughly 1 a.m. local daylight time. Mars now appears 6″ in diameter, making it very small; it is difficult to view surface features with a telescope.

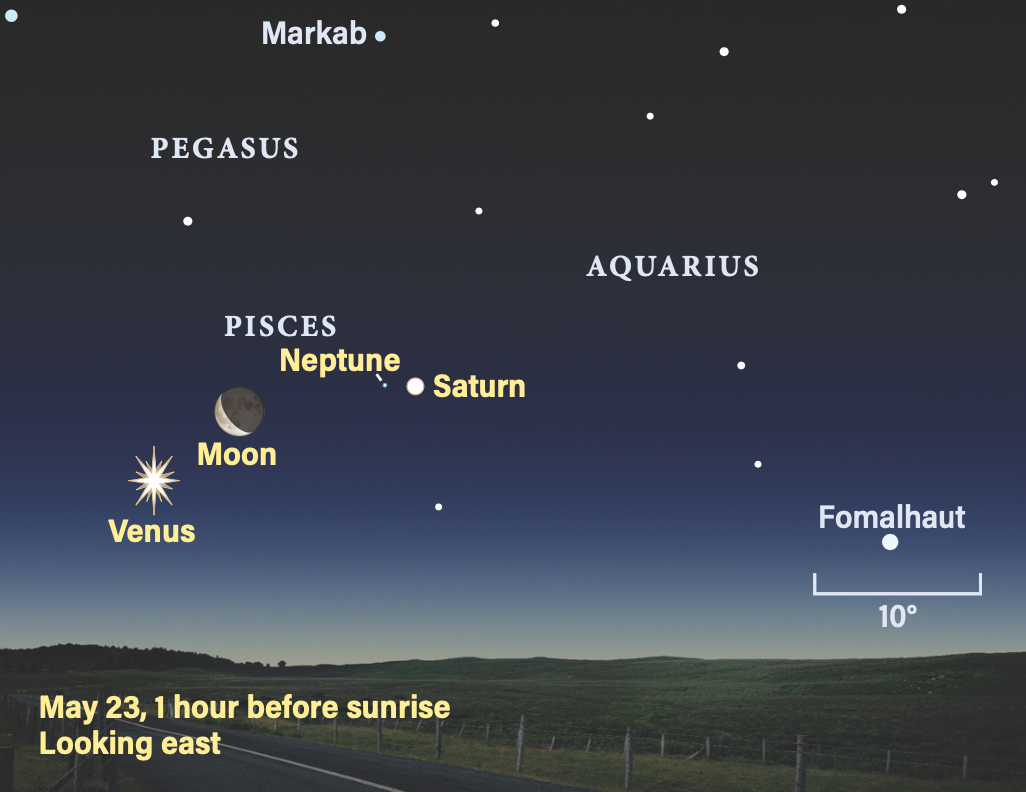

Planetary action moves to the morning, with the appearance of Venus and Saturn climbing high in the predawn sky. Venus is obvious and shines at magnitude –4.7. It’s located south of the Great Square of Pegasus, among the stars of western Pisces.

Saturn stands 4° south of Venus on May 1, a planetary pairing that provides interesting contrast when each is viewed through a telescope. Both planets are above the horizon by 5 a.m. local daylight time. Saturn shines at magnitude 1.2 and its rings are close to edge-on. Venus exhibits a 30-percent-lit crescent spanning 36″.

Neptune also lies in this direction, far beyond both Venus and Saturn, and is difficult to see in early May, when both Venus and Saturn lie about 3° from the more distant world. By the end of May, Neptune stands 1.6° northeast of Saturn and can be spotted with a pair of binoculars, glowing at magnitude 7.8.

Viewing Saturn’s rings is difficult with the low altitude and approaching twilight, but it’s worth a try in the first few days of May because we are glimpsing the backlit side of the rings. If seeing conditions allow, you might see the gossamer-thin black line of the rings’ shadow on Saturn’s 16″-wide disk.

After May 6 — the date of Saturn’s equinox, when the Sun is exactly edge-on to the rings — the shadow essentially disappears. On the next morning, May 7, the southern face of the rings, tilted by 2° to our line of sight, becomes sunlit for the first time in more than 15 years. Observing these fascinating changes in the rings is challenging, but it’s worth the effort if you have a large telescope and clear eastern horizon.

Saturn continues to climb higher in the morning sky and meets with a waning crescent Moon on May 22. By May 31, it’s rising before 3 a.m. local daylight time and stands 15° high in the eastern sky at the onset of morning twilight.

Venus extends its elongation from the Sun during the month and is carried eastward against the background stars of Pisces, away from Saturn. A waning crescent Moon stands within 7° of Venus on the 23rd.

A telescope reveals the disk of Venus diminishing to 24″ during the month. At the same time, its phase grows to 49 percent lit by the last day of the month, when it reaches greatest elongation from the Sun. Venus is best observed in twilight to avoid the dazzling brilliance of the planet when viewed in darkness.

Mercury appears very low in the eastern morning sky in early May, shining at magnitude 0.1. It rises 50 minutes before the Sun on May 1, and only 40 minutes ahead of the Sun by May 12, when the planet has brightened to magnitude –0.5. Its southerly declination makes it a tougher target for Northern Hemisphere observers, whereas those in the Southern Hemisphere have a great view.

If you can catch this elusive planet in a telescope, you’ll spot a gibbous disk growing from 60 percent lit on the 1st to 77 percent lit on the 12th. Mercury quickly dips out of view after the second week of May. Orbiting on the other side of the solar system from Earth, Mercury reaches superior conjunction with the Sun on May 29.

Uranus is out of view and is in conjunction with the Sun May 17.

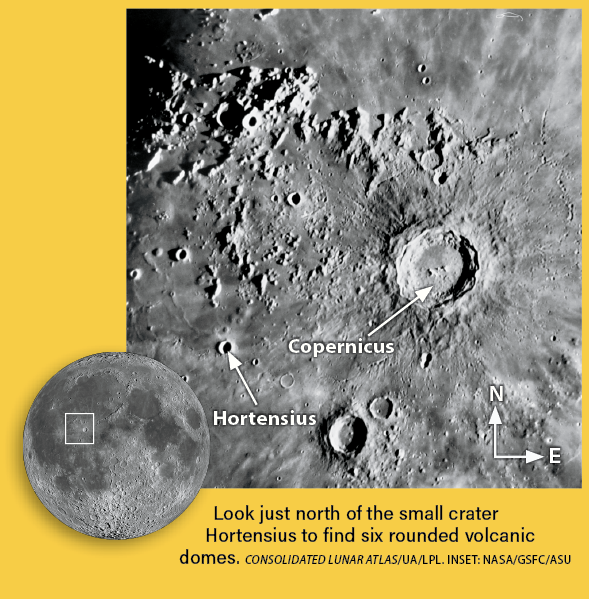

Rising Moon: I lava you

The Moon’s frozen face records the scars of its dual past life, volcanic and bombastic. The prominent impact crater Copernicus is the gateway to this short lunar trip. When it lies on the line separating light from dark, the terminator, its high walls stand out above the surrounding plain. Sunrise over this beautifully complex region occurs on the 6th.

The lit side of Copernicus has a textured surface that looks like the aftermath of a small rock landing in a mud puddle: Apart from a draping of splattered material, numerous secondary pits formed when blast remnants fell shortly after the main impact.

By the 7th, the Sun illuminates the western side, where a bunch of jumbled peaks stick out above the lava-flooded surface. Along the terminator that has shifted to the lunar west is the smaller crater Hortensius. Look closely to the north to see a cluster of six volcanic domes. Each little bump sports its own shadow, but only with a very low Sun angle are these domes noticeable. These light-dark doublets are much softer than the harsher lighting from crater rim to floor.

In his book The Modern Moon, Charles Wood writes that these domes are about 4 miles wide and 1,000 feet or so high. If the night is superb, a 6- to 10-inch scope might reveal a summit pit. Wood notes that despite advances in lunar geology, we don’t know whether they were formed by uplift from below or gradually built up by a longer-term quiet eruption.

Find another large dome just west of Milichius. You could literally spend hours watching the fantastic play of light and dark in the area of Copernicus.

Remember also to look for Mare Orientale at and just after Full Moon. (See last month’s column for more details.)

Meteor Watch: Catch a long train

The warmth of a spring evening is welcome across the Northern Hemisphere. If you venture out at night, you might capture a fleeting view of dust particles ejected from Halley’s Comet on its many orbits around the Sun. They are visible as swift meteors from the annual Eta Aquariid meteor shower, one of two associated with Halley’s orbit (the other is the October Orionids).

The shower is active from April 19 to May 28, and peaks the evening of May 5. The radiant lies near Zeta (ζ) Aquarii, which rises at 2:30 a.m. local daylight time across the U.S., just before the gibbous Moon sets in the west. The radiant reaches an altitude of 20° two hours later, just as the first signs of twilight appear. This low altitude attenuates the zenithal hourly rate of 50 meteors per hour down to an expected observable rate of 10 per hour. These swift meteors travel at roughly 40 miles per second, many with persistent trains, making it worth spending a couple of hours to see perhaps a dozen good meteors, just in time for morning coffee.

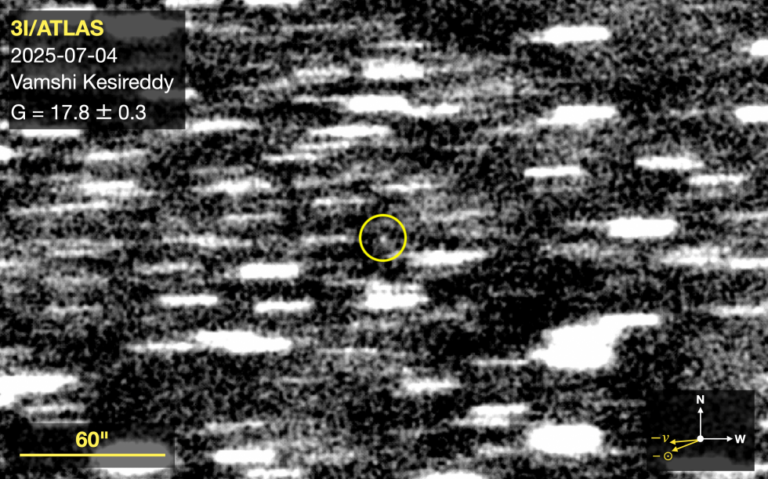

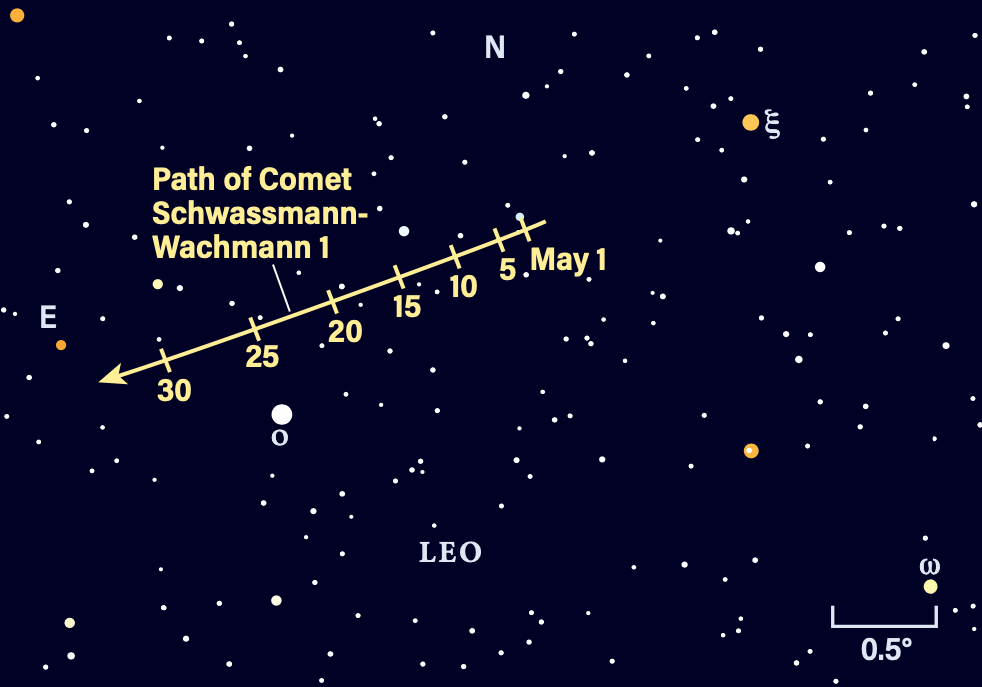

Comet Search: Digging deep in the dark

M95, M96, and M105 in the belly of Leo are targets in the Messier marathon. You’ve primed your eyes and mind on them, now turn to the nearby quirky Comet 29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann. Astronomers can’t predict when it will pop up to 11th magnitude, which it does every year, sometimes twice. You will need an 8-inch scope well away from city lights.

The key to seeing small, faint objects is to make them bigger. Before the information even travels down the optic nerve, your retina bins neighboring cells that “agree” to increase the signal to noise. Sit down to avoid straining, put 100x on M105, then 150x, and even 200x; use a hood, but exhale to the side. Note which magnification best shows its magnitude 11.8 companion, NGC 3389. That’s our comet analogue.

Over at luminary Regulus, ease to the lower right to magnitude 3.5 Omicron (ο) Leonis, then shift north. Use our chart to home in on Schwassmann-Wachmann’s location, and put in your chosen eyepiece. If it’s not immediately visible, dark adapt a bit more and tap the tube to activate the motion sensitivity of your averted vision. You’ve got it when the ghost shows up again in the same spot!

Locating Asteroids: Back on Easy Street

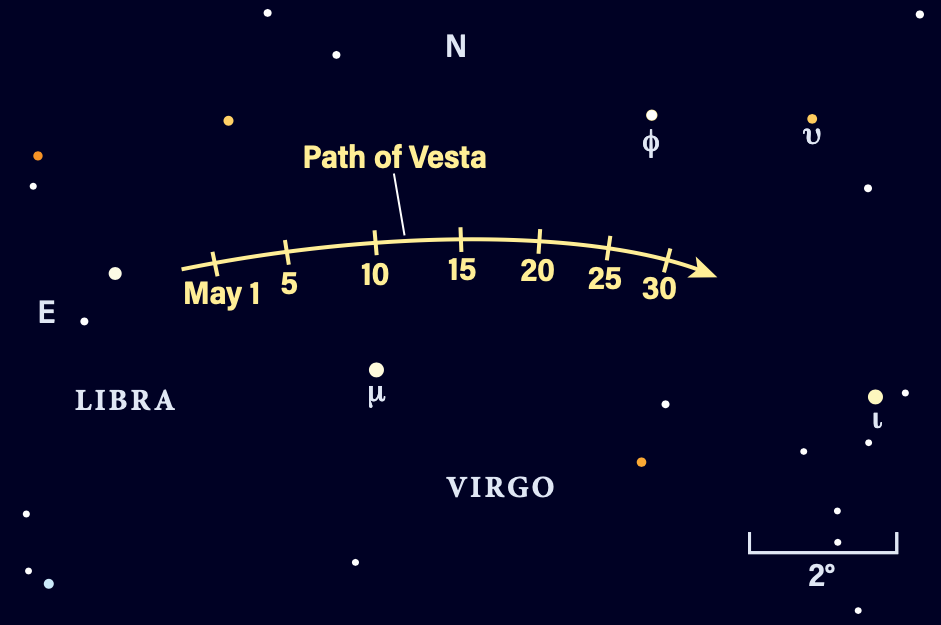

From a city balcony or park, you can spy a main-belt asteroid through binoculars with just a couple of minutes of dark adaptation. Point to a spot halfway between brilliant orange Arcturus and blue-white Spica, and drop two to three fields down. It’s even easier to get to than the directions sound.

Overshoot to hit the lovely wide double star Zubenelgenubi. Evening observers can tilt the finder chart to the left to match the orientation in the sky. Lock in on the gently curving chain of equally spaced stars as you sweep field to field. The only “star” anywhere near the upper two, Mu (μ) and Phi (ϕ) Virginis, is 4 Vesta.

The fourth asteroid to be discovered, Vesta is at peak brightness of magnitude 5.7 on the 2nd, when it lies in opposition to the Sun. When the Moon reaches its opposition — Full phase — it passes so far below that you should be able to follow Vesta the entire month.

See it with unaided eyes too! From a dark site in the last third of May, pick it out during a break from telescopic viewing when it is higher in the sky, above the horizon haze.

Star Dome

The map below portrays the sky as seen near 35° north latitude. Located inside the border are the cardinal directions and their intermediate points. To find stars, hold the map overhead and orient it so one of the labels matches the direction you’re facing. The stars above the map’s horizon now match what’s in the sky.

The all-sky map shows how the sky looks at:

midnight May 1

11 P.M. May 15

10 P.M. May 30

Planets are shown at midmonth