The innermost planets straddle nighttime, with Mercury in the evening and the greatest western elongation of Venus in the morning. Jupiter joins Mercury in early twilight for a few evenings, both setting quickly. Distant Mars lingers with Leo after dark, as our own planet hustles along its orbit well ahead of the Red Planet. Saturn is visible in the early hours, as Neptune hangs nearby and is in conjunction with the ringed planet on the 29th. Uranus reappears in the morning sky before dawn.

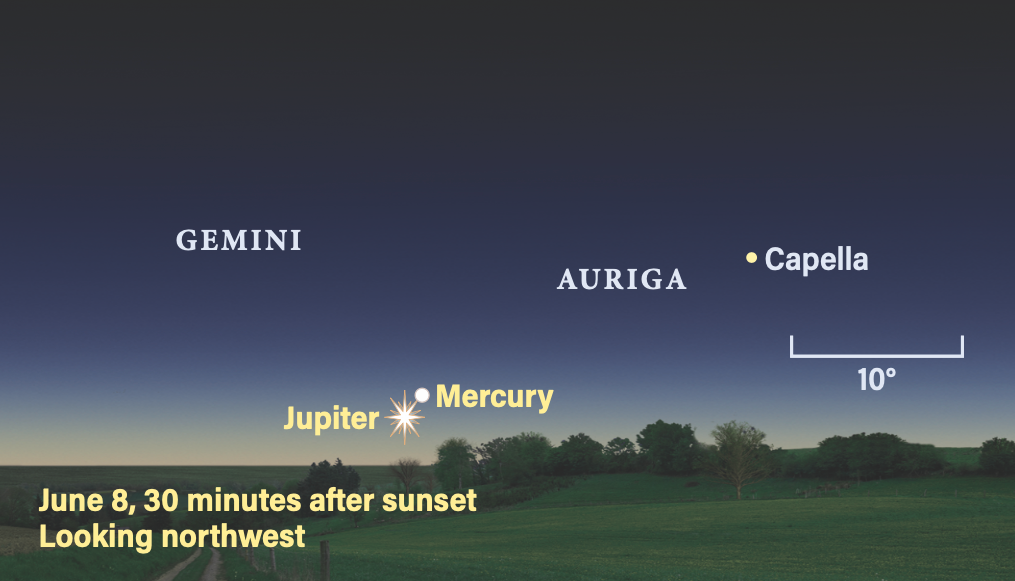

We’ll start in the evening soon after sunset on June 1. You can spot Jupiter hanging low in the western sky. It shines at magnitude –1.9 and becomes visible about 20 minutes after sunset, standing 8° high. Each day it becomes harder to see, but is joined June 6 to 9 by Mercury, which is slowly extending its elongation from the Sun.

Your first chance to spot Mercury is on June 6, when it shines at magnitude –1.5 and stands 3.7° west of Jupiter. The pair of bright planets sits about 3° above the western horizon 30 minutes after sunset. Your observing window is narrow because the planets set together within 25 minutes. Grab a pair of binoculars for the best view in bright twilight, which otherwise makes the two planets challenging to see. Make sure you pick a viewing site with no obstructions. The gap between the planets shrinks to 2.3° by June 7.

June 8 is their formal conjunction, when Mercury stands 2° due north of Jupiter. Jupiter is less than 3° above the horizon half an hour after sunset, while Mercury is 4° high. Mercury has dimmed slightly to magnitude –1.3.

Jupiter is lost from view soon after and heads toward its conjunction with the Sun on the 24th. It’ll reappear in the morning sky in late July.

Meanwhile, Mercury continues to climb higher in the evening sky, though it dims as it goes. On the 13th, at magnitude –0.8, it stands 20′ from 3rd-magnitude Mebsuta (Epsilon [ε] Geminorum). Binoculars give a fine view of the star nestled next to the planet. Look 45 minutes after sunset, when the planet is 5° high in the west.

By June 24, Mercury has dipped to magnitude 0 and lies in line with Castor and Pollux, both 1st-magnitude stars. It sets about 90 minutes after sunset and stands 5° high at 9:30 p.m. local daylight time from latitudes similar to the U.S.

On the 26th, Mercury sits 3.5° to the left of the slender, two-day-old crescent Moon, and by the 30th it lies within 2.5° of M44, the Beehive star cluster. You’ll need binoculars — along with a clear western horizon and good air clarity — to spot the cluster.

It’s worth following Mercury with a telescope throughout June. Its disk is tiny, spanning a mere 5″ on the 6th, when it lies far beyond the Sun. As the month progresses, Mercury moves in its orbit, and by the end of June its disk has grown to 8″ across. During the same period, we see the phase change from a nearly full, 92-percent-lit disk on June 7 to 50 percent lit on the 28th. By June 30, it is a fat crescent, 46 percent lit.

Mars and a waxing crescent Moon shine 8° apart on June 1 in the constellation Leo the Lion. They’re visible high in the western sky as dusk falls. Mars glows at magnitude 1.2 and dims to magnitude 1.4 during June as it moves across Leo. It has a conjunction with Regulus, Leo’s brightest star, on the 16th, standing 48′ due north of the star. Check out the lovely color contrast of these two objects: the orange glow of Mars and the bluish-white hue of Regulus.

Mars continues across southern Leo in the latter half of the month and the Moon rejoins on the 29th, this time less than a degree away. Once the Moon is out of the way on the 30th, look for the galaxy pairing of M95 and M96, standing 2.5° northeast of the Red Planet.

Features on the surface of Mars are difficult to see with the planet standing more than 1.7 astronomical units from Earth. (One astronomical unit, or AU, is the average Earth-Sun distance of 93 million miles.) Its disk spans 5″ at the end of June.

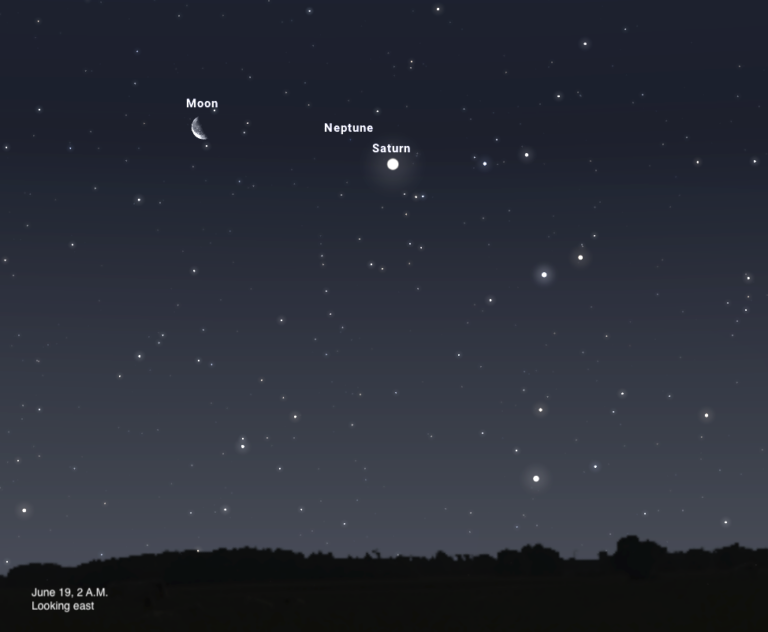

It’s 2:30 a.m. local daylight time on June 1 before the next planet arrives on the nighttime scene, when Saturn rises in the east. At the onset of morning twilight early in the month, it’s about 20° high and within reach for viewing, not long after the ring-plane crossing earlier in the year. Its elevation increases throughout the month, exceeding 35° altitude in the southeast in morning twilight by June 30.

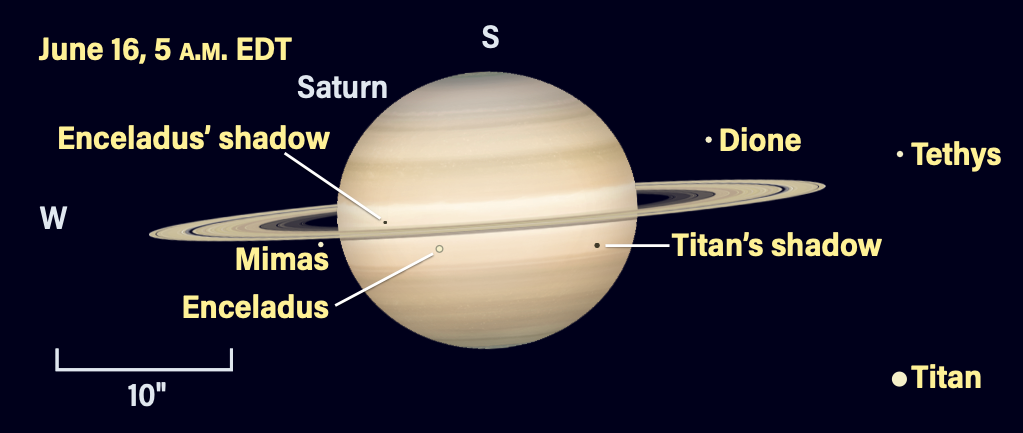

Now — and for the next 13 years — the southern face of Saturn’s rings are on view. The current ring tilt is less than 4°, offering a clear view of the entire disk of the planet. It spans 17″, so check out any dark belts and look for white spots, which indicate upwelling storm clouds and are very rare.

Watch for a special event on the morning of June 16, when a transit of Titan’s shadow begins at 4:11 a.m. EDT. The ringed planet is less than 10° high in the Mountain time zone, with the best views for those in the Eastern time zone. As Saturn rises higher across the Midwest, the dark shadow of the large moon progresses across the disk. It reaches the central meridian around 5 a.m. MDT, not long before sunrise. Such shadow transits are frequent when we’re close to ring-plane crossings (which occurred in March), so expect more in the coming months.

Neptune lies 20 AU (about 1.9 billion miles) beyond Saturn. On the 29th, it is exactly 1° due north of 1st-magnitude Saturn. It’s a great time to find the bluish disk of this distant world. Neptune shines at magnitude 7.8, within reach of a pair of binoculars; Neptune sits to the upper left of Saturn. A few other stars of similar magnitude lie in the region, but all in other directions, so Neptune should be easy to locate.

Through a telescope, Neptune is a challenge, spanning 2″, yet is a view worth beholding as you contemplate this distant world orbiting at the edge of the plane shared by the planets. If you could view the Sun from Neptune, it would appear 30 times smaller than it does from Earth, or just 1′ across. Yet it would still attain a brilliance 500 times that of the Full Moon.

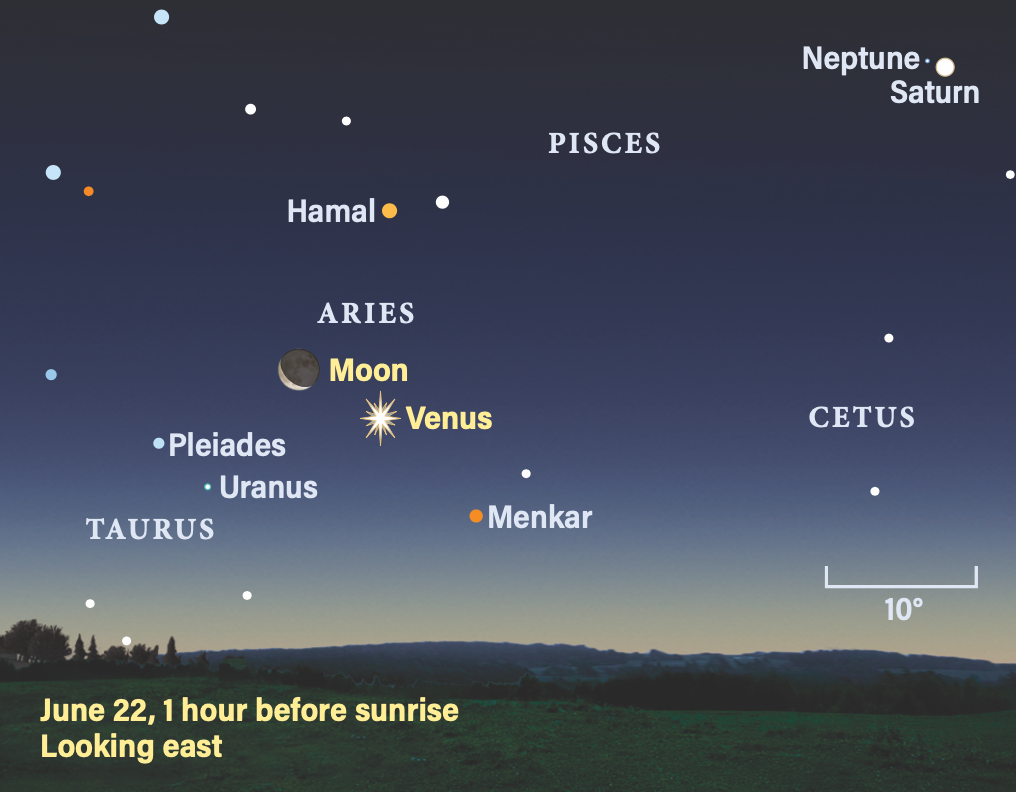

Venus reaches greatest western elongation 46° from the Sun at midnight on May 31. The brilliant planet (magnitude –4.4) rises at 3:30 a.m. local daylight time on June 1 and begins the month located in Pisces the Fish. It traverses Aries from the 10th to the 28th, entering Taurus the Bull just less than 10° southwest of M45, the Pleiades star cluster.

There are two ways to appreciate Venus in the predawn sky: with the naked eye or with a telescope. Later in the month, you can see Venus with the naked eye, along with the Pleiades and Hyades star clusters and the bright, orange-hued star Aldebaran. From June 22 to 24, the crescent Moon joins the scene, adding to the spectacle — perfect for a summer morning photograph. The Moon stands 7° north of Venus on the 22nd.

Through a telescope, Venus reveals additional features this month. On June 1, it shows a 24″-wide, half-illuminated disk, dubbed dichotomy. Do you see it as 50 percent lit? The Schröter effect is in play, where individual perception and light variations in the venusian atmosphere can affect the appearance of the disk, causing dichotomy to occur a few days later than predicted during morning apparitions.

The disk of Venus shrinks to 18″ by the end of June, now exhibiting a gibbous phase that is 64 percent lit. The planet’s increasing distance from Earth has diminished its brilliance slightly, to magnitude –4.2.

Uranus is an easy binocular object for a short period before twilight interferes. The best time to view the planet is June 30, when it stands 5° northeast of Venus. The ice giant’s visibility improves in July.

The summer solstice, when the Sun appears at its northernmost declination for the year, occurs June 20 at 10:42 p.m. EDT.

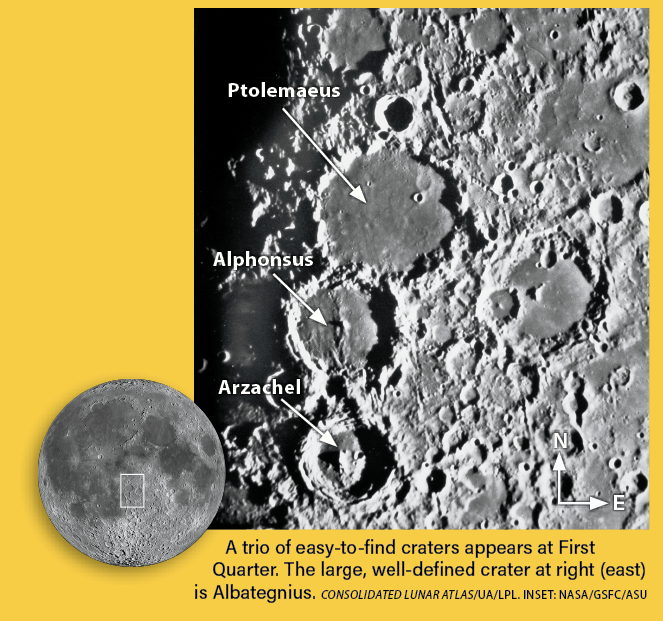

Rising Moon: A terrific trio

“Over here!” A triplet of magnificent large craters practically beckons us on the evening of June 3rd. It’s the Moon in a classic, highly photogenic profile: First Quarter phase. Just below the middle of the Moon, the northernmost and largest of the three, Ptolemaeus, sports a rugged rim that casts long, spiky shadows onto its relatively smooth floor. There is a noticeable small crater pocking the surface, but can you see the tiny craterlet in the northwest?

Like most large impact features, Ptolemaeus has the associated classic slumped walls and complex central peak — if we could dig them out. Scientists figure that they are buried under massive deposits of ejecta spray from the excavation of the giant Mare Imbrium to the northwest. With the low Sun angle on the 3rd, look for subtle round depressions — telltales of ancient craters hiding under a blanket of dirt. They disappear under the higher Sun of the following nights.

The smaller impact that created Alphonsus to the south produced sharper features and a higher central peak. Come back every hour if you can and note how quickly the spire’s shadow retreats under the rising Sun. The unusual ridge bisecting Alphonsus lines up with other linear features that point back to Imbrium as its origin.

Youngest of the three is Arzachel, farther south. The rim and inner walls have better definition than those of Alphonsus and Ptolemaeus, which were beaten by more millennia of impacts. In comparison, Hipparchus to the northeast suffered an even longer period of bombardment.

There is still more to see on the following nights, as surface composition is revealed under a higher Sun. The floor of Alphonsus sports a handful of darker gray spots. These are deposits of volcanic ash, somewhat gently sprayed out from their central cones. Spectroscopic studies indicate the ash is similar to the lava that welled up to create the large seas.

If you’re up past midnight, look just south and west of the trio to see the black triangular shadow of the Straight Wall emerging from the lunar darkness. Otherwise, come back on the 4th.

All features will have shorter shadows when you return July 3rd for another look.

Meteor Watch: Welcome the clouds

No major meteor showers occur in June, but warm summer nights are appealing to lie out under the stars, watch the Milky Way wind through Cygnus and Aquila, and catch those occasional sporadic meteors at random moments.

The occurrence of noctilucent clouds during summer is an additional treat for those observing from northerly latitudes. These iridescent clouds glow long after regular clouds appear dark. Noctilucent clouds lie 10 times higher than cirrus, and are produced when ice crystals form on tiny dust particles in our atmosphere. If you see them, they appear stationary, but time-lapse photography reveals the beautiful ebb and flow of these elusive clouds.

Comet Search: Troll deep and hope

Comets that climb to binocular brightness too fast to be highlighted in this column are discovered on average once a year. Five years ago, there were four surprises, one of them the marvelous C/2020 F3 (NEOWISE). Clearly June is too early to be announcing a comet of the year.

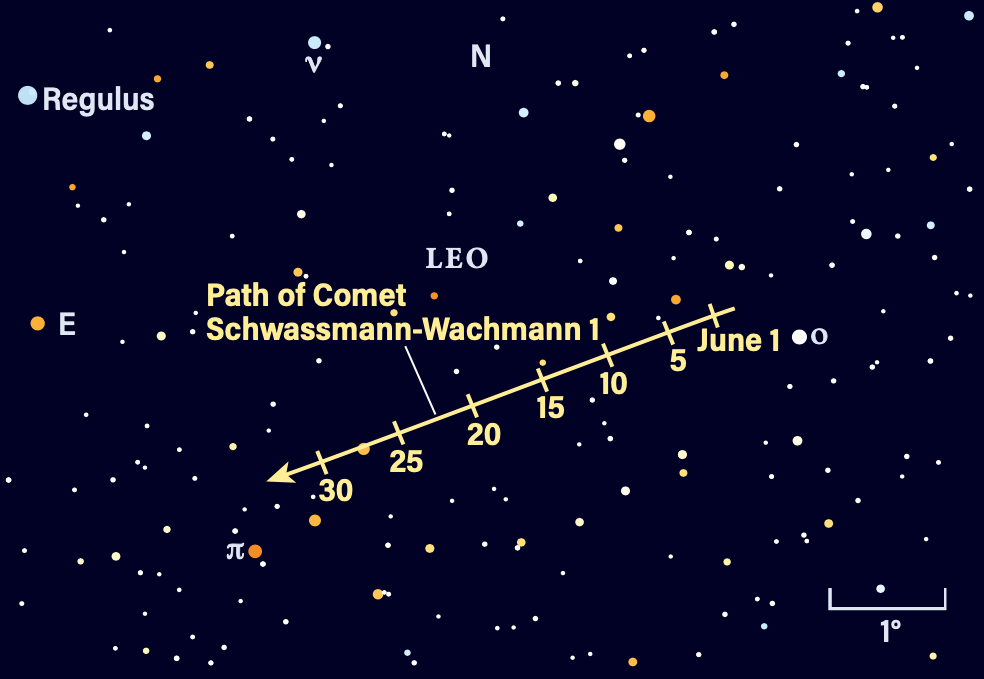

Comets emit light from fluorescing gas, notably the long blue tail streaming outward and the eerie green glow surrounding the coma. But most often, it’s the liberated dust scattering sunlight that contributes the most to a comet’s brightness. Comet 29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann, beyond the orbit of Jupiter, has puffed out clouds of dust at irregular intervals for decades without breaking apart like most others. If we’re lucky, it will be glowing at 11th magnitude this month, sporting a 3′ to 5′ halo and bright central false nucleus.

Schwassmann-Wachmann 1 is best during June’s last two weeks, when the Moon isn’t interfering. Target it as night falls before it sinks too low. Drop south of Regulus to Pi (π) Leonis and nudge your scope westward to a 6th-magnitude field star as guidepost. To prepare yourself, try galaxy NGC 3049 (magnitude 12.5) at powers above 150x.

Locating Asteroids: Five-minute asteroid gazing

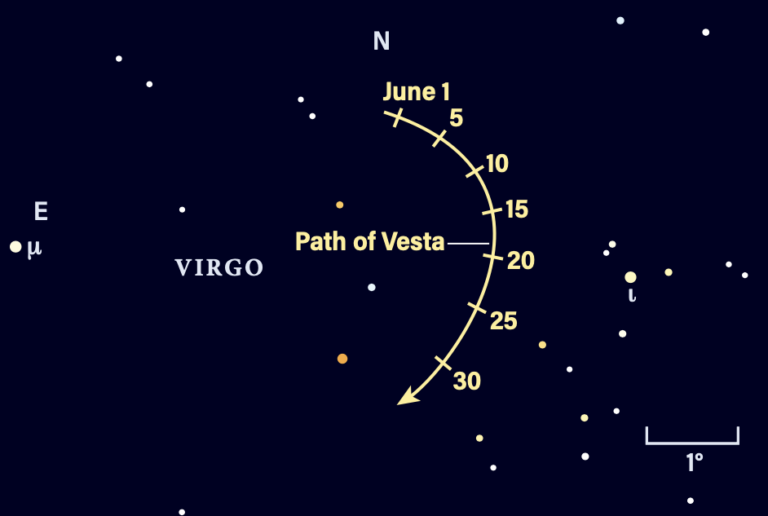

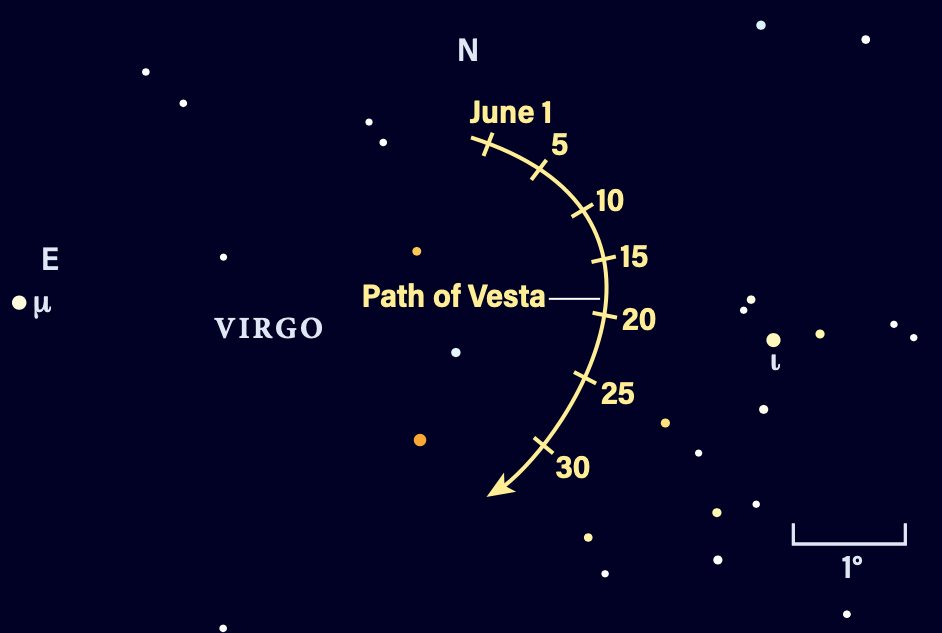

Get a kick out of following an asteroid from your city balcony or backyard with only five minutes of dark adapting. The offer ends this month and isn’t back for a full year. The second-largest object in the main belt, 4 Vesta shines at magnitude 6.1 but slowly fades to 6.7 by the end of June, as faster-orbiting Earth leaves it behind.

Slowly scan your binoculars 15° northeast (to the upper left) of blue-white Spica. Find the outline of a tilted bell dotted by 5th- to 6th-magnitude stars, just fitting in the field of view at 7x. Place those dots in a logbook, along with the next four brightest, in the middle — one will be Vesta. Return every three nights or so to see it has shifted. The Moon passes by on the 6th and 7th, but more than 10° to the south. With Vesta so bright, this shouldn’t be an issue.

Vesta was discovered in 1807 by Heinrich Olbers, six years after Ceres. Its high reflectivity (albedo) of 0.38 lets it outshine the dwarf planet despite being half its size.

The 8th offers an excellent chance to watch a different asteroid move in less than two hours. Passing only a few arcminutes north of Regulus and its 8th-magnitude companion, 29 Amphitrite (magnitude 11.2) starts the night creating a crooked line and ends it as part of a tight triangle.

Star Dome

The map below portrays the sky as seen near 35° north latitude. Located inside the border are the cardinal directions and their intermediate points. To find stars, hold the map overhead and orient it so one of the labels matches the direction you’re facing. The stars above the map’s horizon now match what’s in the sky.

The all-sky map shows how the sky looks at:

midnight June 1

11 p.m. June 15

10 p.m. June 30

Planets are shown at midmonth