Key Takeaways:

- Several planets, including Mercury, Mars, Venus, Uranus, Neptune, Saturn, and Jupiter, are visible this month.

- Saturn's moon Titan will cast its shadow on Saturn twice during July.

- Neptune will be easy to find near Saturn.

- Pluto is at opposition in July, offering the best viewing opportunity of the year.

Summer nights offer lots of interesting sights this month. Mercury and Mars are on show in the evening twilight. Both Uranus and Neptune stand near brighter beacons: Neptune and Saturn are two Moon-widths apart all month, while the morning sky hosts Venus and Uranus together in Taurus. Saturn also shows off two Titan shadow transits, visible through small telescopes. Jupiter returns late in the month, as Pluto reaches opposition.

Mercury hangs low in the west soon after sunset, shining brightly at magnitude 0.4. It outshines Regulus, Leo’s brightest star, by a full magnitude.

Mercury stands 1° southwest of the Beehive Cluster (M44) on the 2nd. If you have a clear western horizon and transparent air, binoculars may show a fuzzy hint of M44 in the darkening twilight, although any horizon haze will wash it out.

Mercury reaches its greatest eastern elongation on the 4th, 26° east of the Sun. The planet now stands 4° high an hour after sunset. The 4th-magnitude star Asellus Australis (Delta [δ] Cancri) lies 20″ from Mercury, although the star will be hard to see through any haziness.

If your scope can resolve Mercury’s 8″-wide disk at low altitude, it is 45 percent lit on the 1st. It slims to 39 percent by the 4th and to 22 percent by the 14th, when it spans 10″.

Mercury’s visibility diminishes quickly in the second week of July, dimming to magnitude 1 by the 12th and magnitude 1.5 by the 17th. Additionally, Mercury stands only 2° high 40 minutes after sunset on the 15th. You can try catching it earlier, but the sky is brighter and Mercury’s faint glow will be increasingly challenging each consecutive evening.

Mercury drops from view quickly and reaches inferior conjunction with the Sun at the end of the month.

Mars starts the month at magnitude 1.4, visible low in the west after sunset. It drops by 0.2 magnitude for the latter half of July. Throughout the month, Mars travels across southern Leo. On July 1, the Red Planet stands 8° east of Regulus and is 22° high one hour after sunset.

Also on the 1st, a fine waxing Moon lies 24° southeast of Mars. On July 27, a slimmer crescent Moon stands 8.5° west of Mars — the same day Mars crosses from Leo into Virgo. The Moon stands 4° southeast of Mars on the following night, July 28. Look an hour after sunset, because now Mars is only 12° high in the western sky.

Even through a telescope, Mars’ disk shows little detail, due to its small angular size (less than 5″ by the end of the month). While the Red Planet remains visible for many months in the evening sky, the telescopic view doesn’t improve.

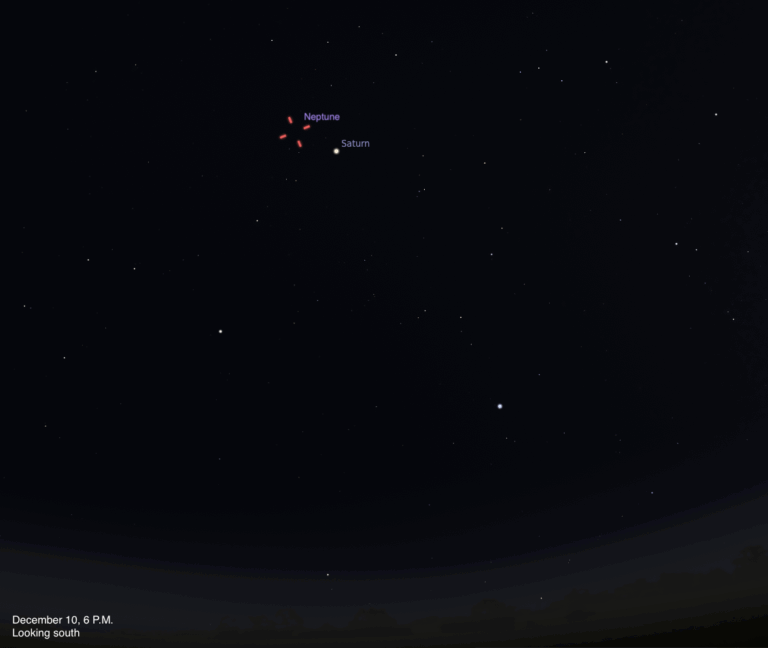

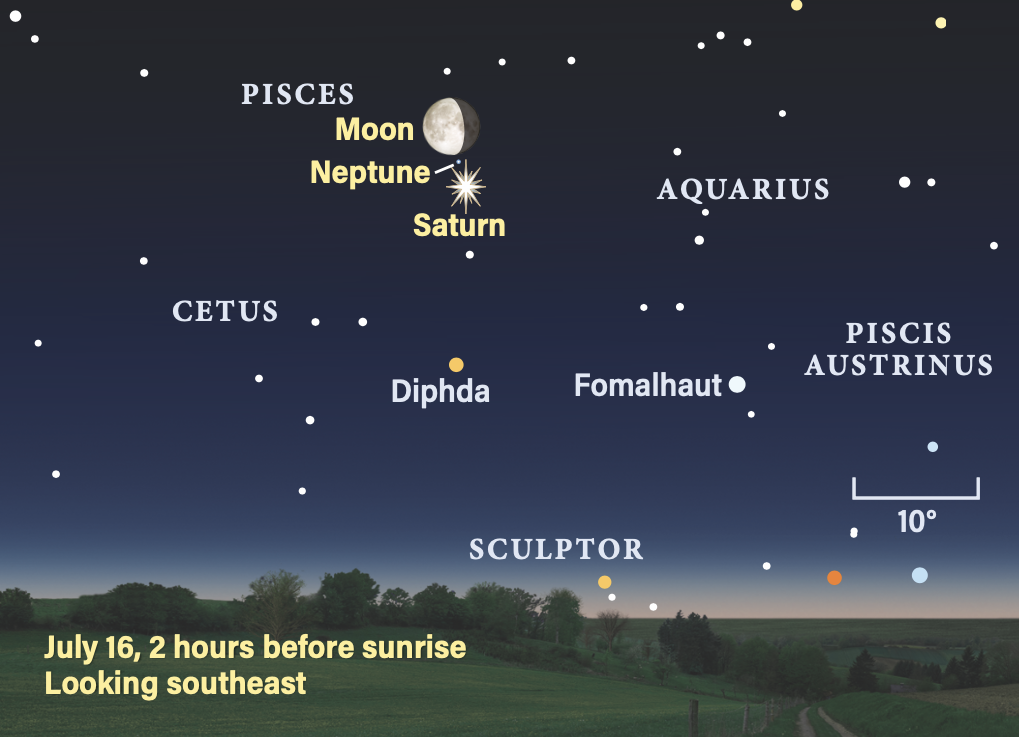

This summer is a great time to spot Neptune. All you need is binoculars. Neptune remains about 1° north of Saturn all month, making it easier to identify than usual. A waning gibbous Moon stands 3° north of Saturn on July 16, with Neptune nestled between them.

Saturn and Neptune rise together around midnight local daylight time. Saturn shines at magnitude 0.9 and is an easy object low in the eastern sky an hour after it rises. Neptune is magnitude 7.7 and is obvious north of Saturn in a low-power telescope eyepiece. Viewing both planets together is rare. Consider the amazing fact that Neptune lies nearly 1.9 billion miles beyond Saturn!

The two planets lie in Pisces, southeast of the Circlet. They’re well placed in the two hours before dawn, more than 40° high in the southeastern sky. Both Saturn and Neptune reach a stationary point in their easterly motion. Neptune halts on the 5th, and Saturn on the 14th. Watch each night as their relative positions slightly change, the two distant planets performing an elegant slow dance.

Neptune spans a mere 2″ and reveals a bluish hue through a telescope. Saturn’s disk spans 18″, an easy target in any telescope. We have a fine view of the southern face of the rings, which are tilted some 3.6° to our line of sight. Watch for any unusual bright cloud features on Saturn’s disk.

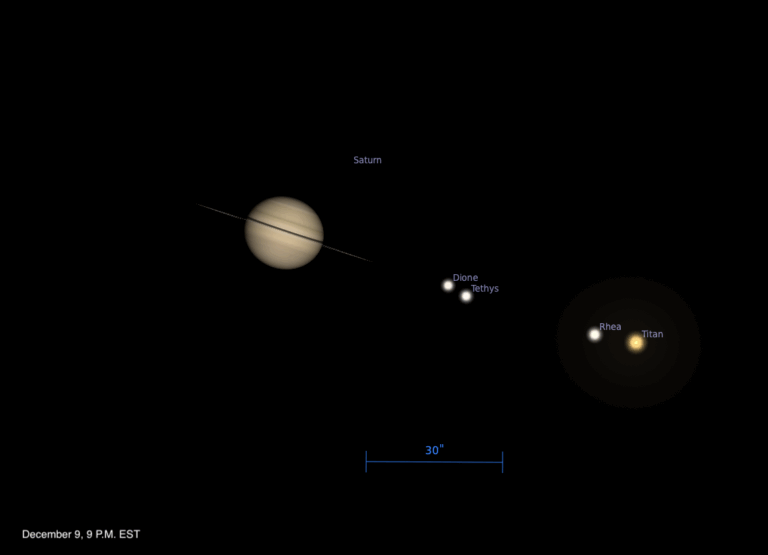

Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, shines at magnitude 8.5. It’s easy to spot in small telescopes as it circles the ringed planet every 16 days. Due to the shallow tilt of its orbit, Titan’s shadow transits Saturn’s disk, and the next couple of months offer repeat opportunities to view this.

Titan’s shadow begins a transit July 2 around 3:30 a.m. EDT. It takes a few minutes for the shadow to appear and will depend somewhat on your seeing conditions. By 4 a.m. EDT, the shadow should be distinctly visible on Saturn’s disk, and West Coast observers will have a chance to see the later stages as Saturn rises. The full shadow transit takes more than five hours; the shadow is roughly midway across the disk by dawn across the Midwest. Titan itself passes north of the disk.

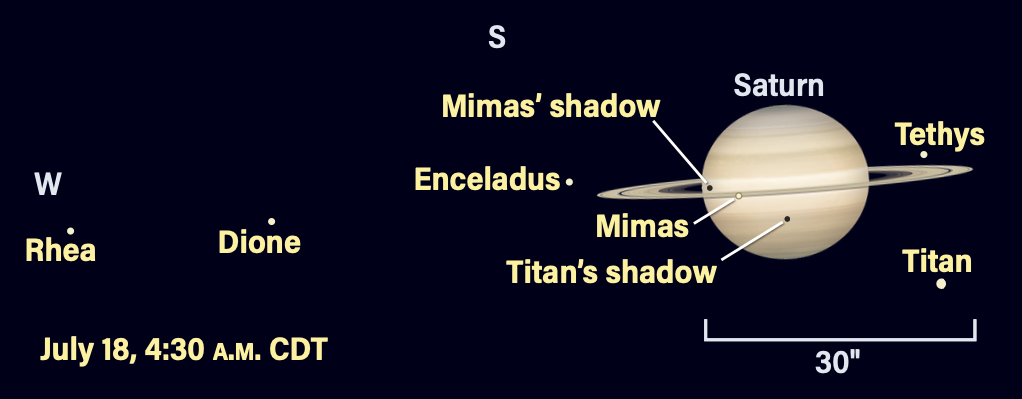

There’s a repeat shadow transit July 18 starting about 2:50 a.m. EDT. It reaches midway across Saturn’s disk around 4:30 a.m. CDT, just as dawn breaks across the East Coast, with the latter half of the transit visible from the western half of the U.S.

Saturn has a host of other moons. The most visible are Tethys, Dione, and Rhea, all within Titan’s orbit and shining at 10th magnitude. Enceladus orbits just outside the edge of the rings and shines at 12th magnitude, challenging to spot with the brilliant disk of Saturn dominating a telescopic view.

Iapetus lies 1.4′ due south of Saturn on July 1, shining near 11th magnitude. It then heads east of the planet, dimming to 12th magnitude by the time it reaches greatest eastern elongation on the 21st, when it stands 9′ from Saturn. The dimming is due to the darker half of Iapetus rotating to face Earth.

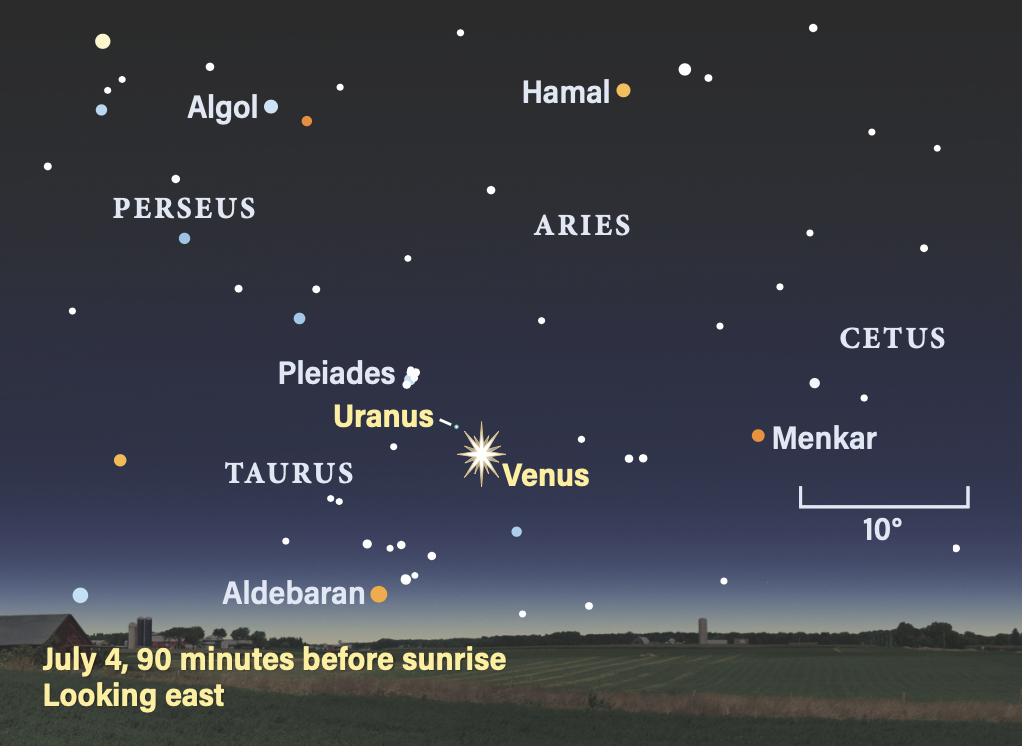

Venus and Uranus are located in the same region of Taurus the Bull in early July. Venus is obvious, shining at magnitude –4.1 and rising around 3 a.m. local daylight time. Uranus is nicely placed 4° due south of the Pleiades (M45).

Uranus shines at magnitude 5.8, making it an easily binocular object. Venus lies in the same vicinity for a few days in early July, aiding its identification. On July 4, Uranus is 2.4° due north of Venus. There’s also a nice pair of 6th-magnitude stars due west of Uranus. A telescope will show the ice giant’s pale bluish-green, 3.5″-wide disk.

Venus moves east as July progresses and stands 3° due north of Aldebaran on the 14th, after skirting the northern regions of the Hyades cluster for a few days. A crescent Moon stands nearly 8° northwest of Venus on the morning of the 21st. On the morning of the 26th, Venus lies 44′ northwest of Zeta (ζ) Tauri, the southern “horn” of Taurus.

Deep-sky observers will recognize this location as very close to M1, the Crab Nebula. The nebula stands 0.5° north of Venus. It’ll be interesting to try to see M1 and Venus in the same field of view — watch for any spurious lens flare from Venus masquerading as the nebula. Small nudges to your scope will reveal which smudge is M1.

A telescope will show Venus’ changing appearance. On July 1, it spans 18″ and reveals a 64-percent-lit gibbous phase. By the 31st, it has grown to 75 percent lit and 14″ across. Venus spends the last three days of July in northwestern Orion.

Jupiter reappears in the morning sky in late July. The gas giant lies in western Gemini, shining at magnitude –1.9 and rising shortly before 5 a.m. local daylight time on the 14th. Watch the eastern horizon on July 23 as Jupiter rises soon after 4 a.m. local daylight time, along with a fine crescent Moon 5.5° to its left (northeast). By the end of July, Jupiter is clear of the horizon, along with all the stars of Gemini, just as dawn breaks.

Pluto reaches opposition July 25. The dwarf planet is 3.2 billion miles from Earth, wandering among the stars of southwestern Capricornus at a declination of –23°, well south of the ecliptic. Consequently, it never rises very high. This month is the best opportunity to see it, as it lies due south at its highest elevation at 1 a.m. local daylight time.

The dwarf planet glows at magnitude 15.1; detecting it visually will require a large telescope exceeding 16 inches and dark observing conditions. There’s some help near Pluto’s location: two stars at magnitude 7.7 and 7.8 that sit side by side, aligned east-west. The stars stand 39′ apart. Find them by starting at 4th-magnitude Psi (ψ) Capricornus. Move 5.2° northwest to find the easternmost star in the pair. Pluto is 22′ due north of this star on June 25 and wanders westward throughout July. It forms an equilateral triangle with the two stars on July 12, and skirts 1′ to 2′ south of a 10th-magnitude star over the next two nights. A note of caution here: The 10th-magnitude star has a 15th-magnitude star just 43″ due south of it. On July 13, Pluto lies at double that separation and is slightly fainter.

On the 26th, one day after opposition, Pluto reaches a point 9′ due north of the westernmost 8th-magnitude star previously mentioned. Note there are many 12th- and 13th-magnitude stars in the same region of Capricornus.

If you already have a nice astrophotography setup with your telescope, recording Pluto requires only a couple of minutes of exposure with a cooled camera. Targeting the two 8th-magnitude stars with a system that has at least a 30′-wide field of view will also capture Pluto.

Rising Moon: The end of the standstill

There’s a shifting pattern of moonrises at Full phase that caught the eyes of the ancients. It’s just finished bottoming out, making an easy start for you to ride the wave of the next 18.6-year cycle. Echoing the way winter sunrises head to the southeast, stop at the solstice, and return northward, Luna’s summer moonrises do the same but with a surprise. This year, the moonrises are an extra 7° farther south, quite a lot for an avid watcher of the skies. Halfway into the cycle — in 2034 — they will fall 7° closer to the east.

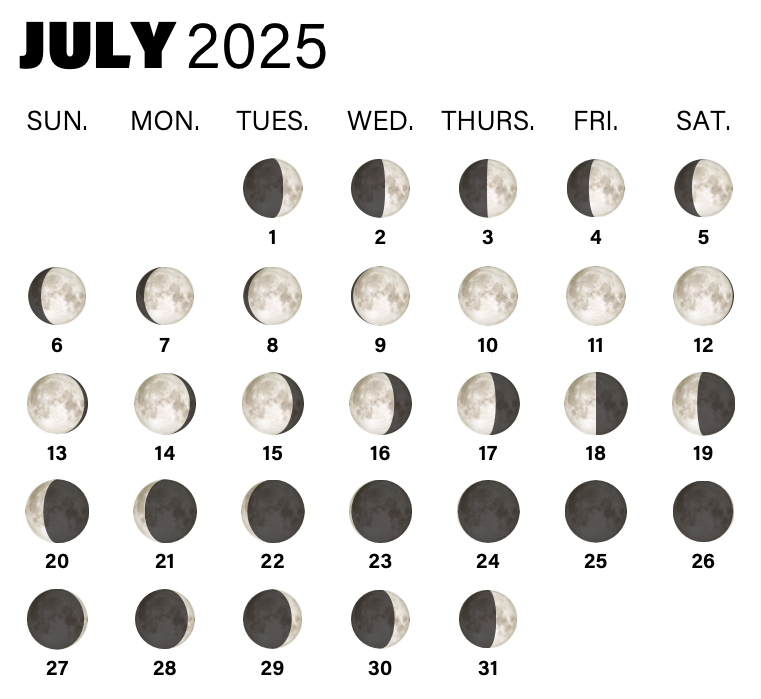

It’s easier to notice this lunar standstill when you have prominent features at the horizon, like hills or notches, or distant trees or buildings. Most importantly, you’ll need a viewing location to which you can reliably return. You’ll have four chances from the 7th through the 10th to spot the Moon rise at its farthest south.

To help visualize this, look how the blue line of the Moon flows on the Paths of the Planets diagram, low through Scorpius and Sagittarius, high in Taurus and Gemini. This is the 5° tilt of the lunar orbit, rotating like a twirling hula hoop’s contact point. The high point will be in Pisces in a few years.

Watch for the Full Moon’s shallower rise angle and extra-low arc across the southern sky. With more atmosphere to pass through, Luna’s face will be yellower, even pale orange.

Meteor Watch: Double feature

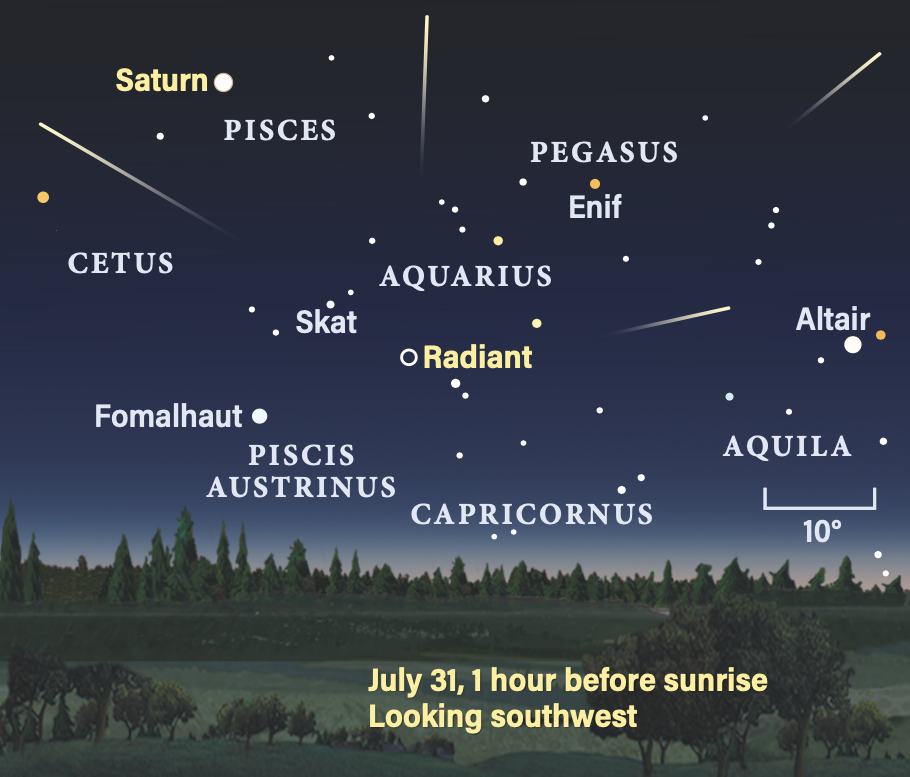

The summer meteor season begins in July. The combination of a few minor showers with low hourly rates contributes to a strong chance of catching a meteor during the dark moonless hours of night.

The Southern Delta Aquariids are active starting the 12th and build slowly through the first three weeks of July. Near the peak on July 31, if the radiant were overhead it would produce about 25 meteors per hour. The radiant is near the 3rd-magnitude star Skat in Aquarius, and climbs to 25° altitude from North America in the hour before dawn. Watch for maybe a dozen meteors per hour.

This shower is joined by the start of the annual Perseids July 17, so by the end of July you can expect a few meteors per hour from a very different direction than Aquarius. It’s fun to see if you can identify members of both showers on a clear morning.

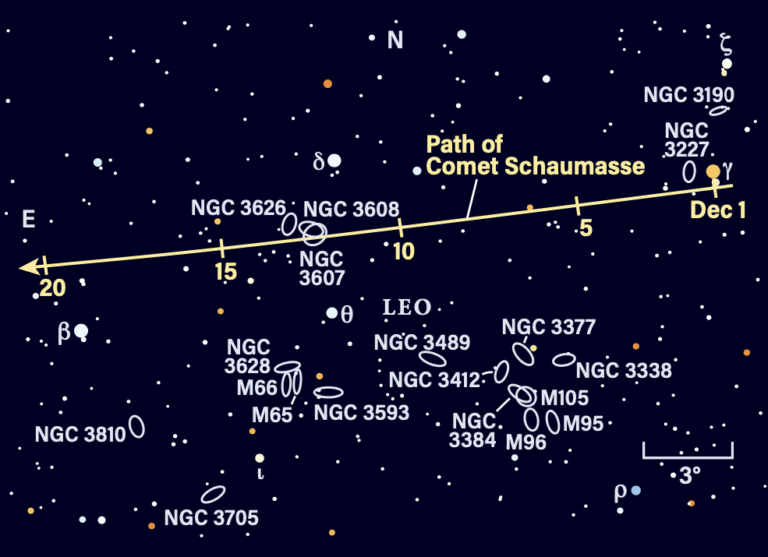

Comet Search: Magnitude mashing

When Comet C/2023 A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS) reached magnitude –6 last October, why was Venus, two magnitudes fainter, easier to see? A more compact light source punches through skyglow, while diffuse light from an expansive comet tail is too faint to compete with the twilight.

A comet’s integrated magnitude comes from adding together the light from its tail as if it were compressed into a star. Comet discoverer David Levy recommends the in-out method to visually estimate a comet’s total brightness at the telescope. In a nutshell, study the comet’s in-focus apparent size and average brightness through the eyepiece. Now find a slightly brighter star, take it out of focus to make it the size of the comet, and compare. Jump to different stars until you get a reasonable match. Notice how much the star fades the bigger you make it, perhaps to disappearance.

Practice on some globulars, clustered near our galactic center. Start with M28 at the top of Sagittarius’ Teapot. Compare the in-focus magnitude 6.8 M28 with the out-of-focus three stars to the west and southwest. Don’t expect precision at this stage. Try it with fainter magnitude 9.0 NGC 6638 and magnitude 9.1 NGC 6642. Then there’s the real challenge: magnitude 11.0 Palomar 8 a few degrees north. Use M22 as a substitute binocular comet. The in-out method gets easier the more you practice.

Comet C/2024 E1 (Wierzchoś) breaks past 13th magnitude next month, perhaps reaching magnitude 5.5 in January.

Locating Asteroids: Snap sightings

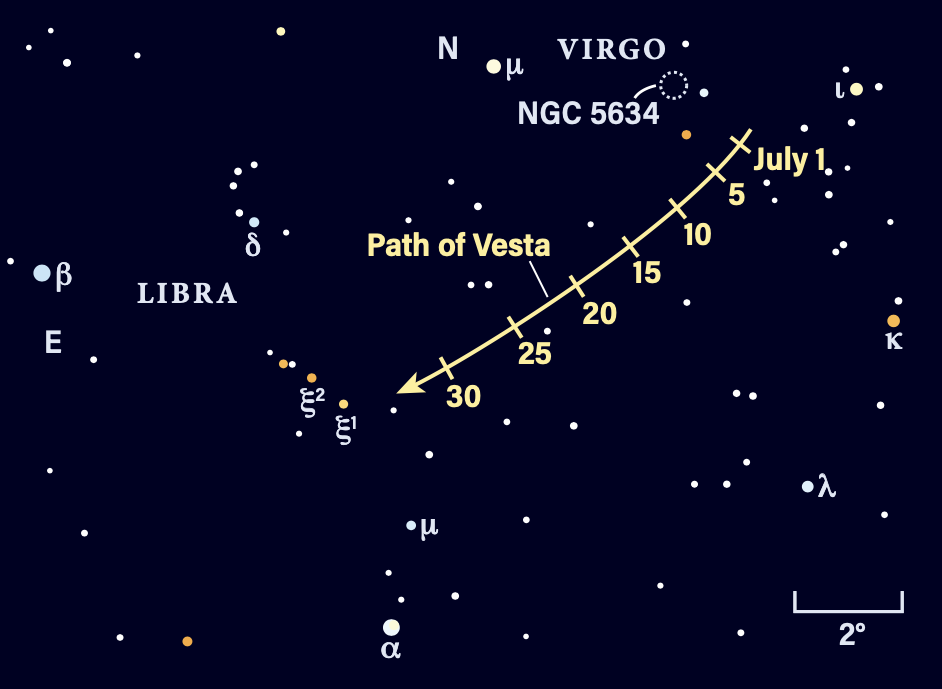

When you can’t take the time for a full session, even 10 minutes of observing helps you relax after a long day and before the next one. Step outside with binoculars and you’ll be seeing asteroid 4 Vesta within a few breaths.

Familiarize yourself with Alpha (α) and Beta (β) Librae almost due south as twilight fades, halfway between luminaries Spica and Antares. It will take six weeks for Vesta to split these stars, time for you to have a quick peek every three or four nights and notice it shift toward Antares. As July opens, Vesta lies between the feet of Virgo, Mu (μ) and Kappa (κ) Virginis, a fainter echo of Libra’s lights.

If you’re using a scope to follow the main-belt world, give the distant globular cluster NGC 5634 a try. From the suburbs, its core should mimic a fuzzy 10th- to 11th-magnitude star. Avoid the first week of the month, when the bright Moon is not far.

There are so few background stars here that a go-to scope from the city will land you on Vesta with nothing else in a 1° field of view. The slow fade from magnitude 6.7 to 7.2 comes as Earth leaves it behind. On the 19th, the 330-mile-wide space rock pretends to be the brighter component of a wide, unequal double star. July 19–21 and 30–31 are good chances to see Vesta move compared to other stars at low power over a run of nights.

Star Dome

The map below portrays the sky as seen near 35° north latitude. Located inside the border are the cardinal directions and their intermediate points. To find stars, hold the map overhead and orient it so one of the labels matches the direction you’re facing. The stars above the map’s horizon now match what’s in the sky.

The all-sky map shows how the sky looks at:

midnight July 1

11 p.m. July 15

10 p.m. July 31

Planets are shown at midmonth