Key Takeaways:

- Jupiter achieves opposition on January 10, providing optimal viewing of its extensive atmospheric details and dynamic Galilean moon transits, including a rare overlapping shadow transit of Callisto. Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune are also favorably positioned for observation, with specific guidance for their telescopic or binocular visibility and notable features like Saturn's ring tilt and moon configurations.

- The Quadrantid meteor shower peaks on January 3, though its visibility will be significantly curtailed by lunar illumination, limiting observations primarily to brighter meteors and fireballs. Furthermore, two comets, 24P/Schaumasse and C/2024 E1 Wierzchoś, are identified as potential telescopic and binocular targets, respectively, with notes on their expected brightness and appearance.

- Specific lunar topographical features, such as the Hyginus and Ariadaeus rille complexes and a distinctive "hoofprint" formation, are presented for detailed observation under varying illumination conditions. Concurrently, the asteroid 16 Psyche is observable through small telescopes near Aldebaran, with instructions provided for its positional tracking.

- Mercury offers a brief observational window in the morning sky around New Year's Day, while Venus and Mars are not visible throughout the month due to their superior and solar conjunctions, respectively.

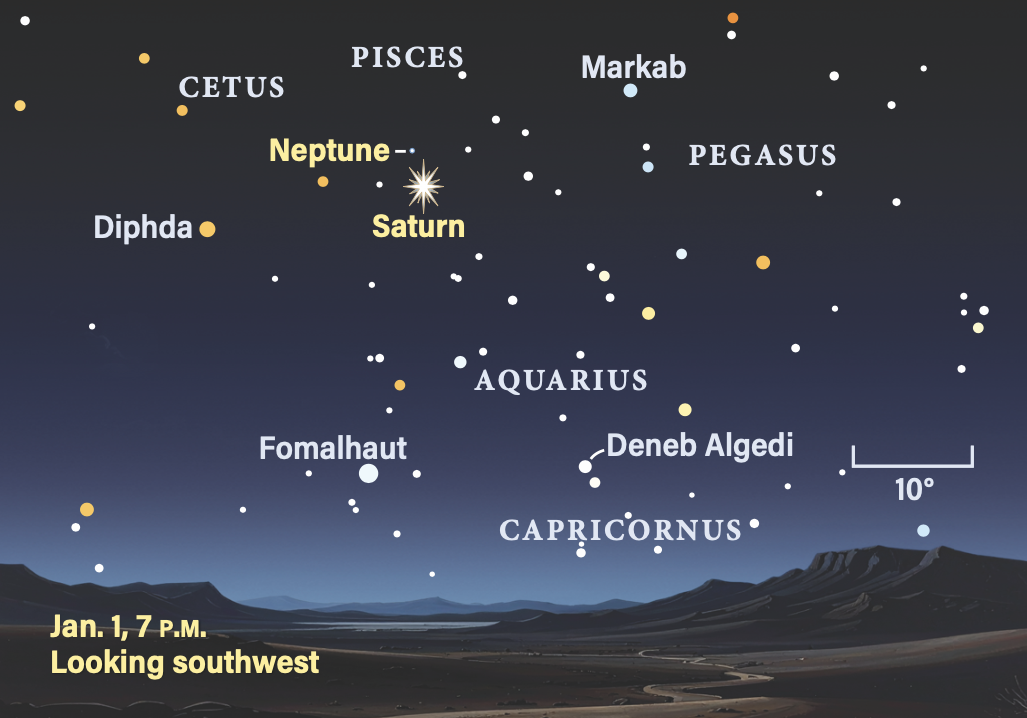

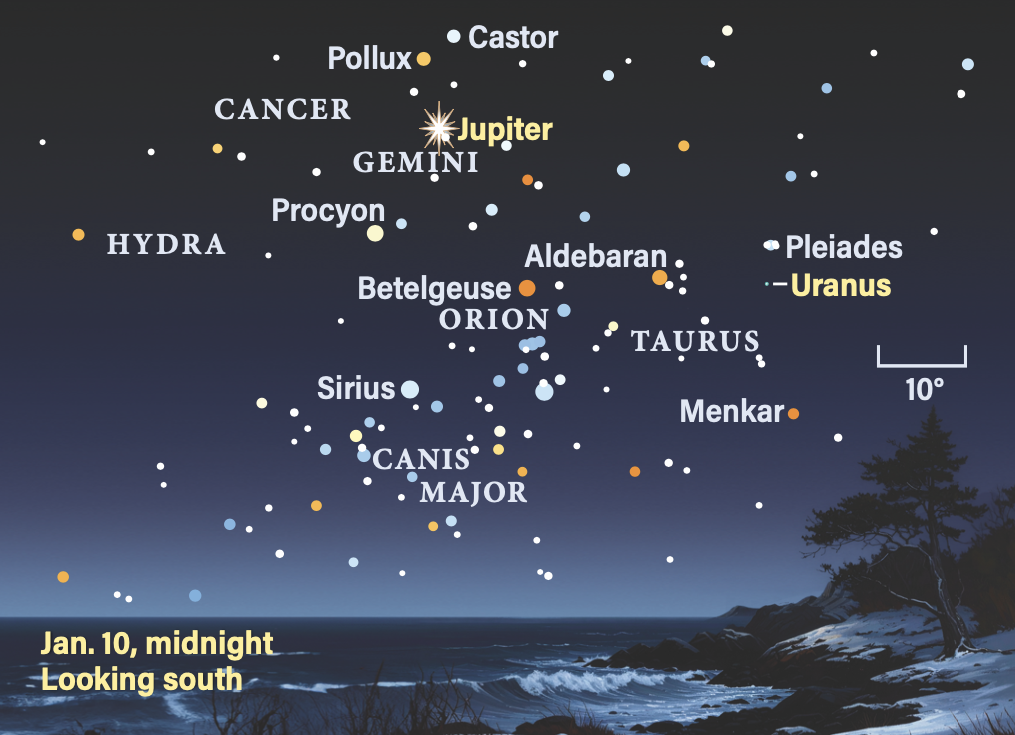

Saturn is on display in the early-evening sky this month along with Uranus and Neptune, both within reach of binoculars. Jupiter dominates the night, reaching opposition on the 10th. The gas giant is the prime target for the month; the long winter nights offer lots of time to enjoy the view. Mercury continues its year-end showing through the New Year, visible in the morning sky for a brief time.

Saturn and Neptune remain in the same binocular field of view all month. Saturn is easy to spot, shining at magnitude 1.0. It crosses from Aquarius into Pisces on the 15th. Neptune stands 3.5° northeast of Saturn on the 1st, and Saturn’s path brings it to within 1.7° of Neptune by the 31st. Neptune shines at magnitude 7.8, requiring optical aid to see it. Catch these two planets early in the evening, as they set before midnight.

Neptune lies 2.8 billion miles from Earth and its disk spans only 2″. With Saturn in your field of view, move northeast to find the dim, bluish-hued disk. Its nonstellar appearance will give it away.

Saturn lies much closer at 924 million miles from Earth, and its disk spans 17″. The rings show a very shallow tilt, beginning January at 1° and increasing to 2.2° by the 31st. The thin rings will almost disappear in small telescopes. The entire disk of the planet is visible, with some subtle features in its atmosphere evident to patient observers who wait for steady moments of good seeing.

Eighth-magnitude Titan is the largest moon. It wanders back and forth every week during its 16-day orbit. You’ll find the moon near Saturn on Jan. 1, 9, 17, and 25.

Tethys, Dione, and Rhea, all shining at 10th magnitude, orbit Saturn interior to Titan. They undergo close conjunctions at regular intervals, often near the rings, which are fascinating to view. Enceladus shines at 12th magnitude and is often hard to see due to the nearby brilliance of the rings, but it’s easier now. It remains within about 37″ of Saturn, or about 15″ beyond the edge of the rings at the extremes of its orbit.

Iapetus reaches inferior conjunction with Saturn Jan. 14, when the 11th-magnitude moon stands 1.2′ due north of the planet. Iapetus moves west of Saturn during January and slowly increases in brightness as its lighter hemisphere turns earthward. As it approaches its early February western elongation, the moon brightens to 10th magnitude and reaches a point nearly 8′ west of Saturn by month’s end.

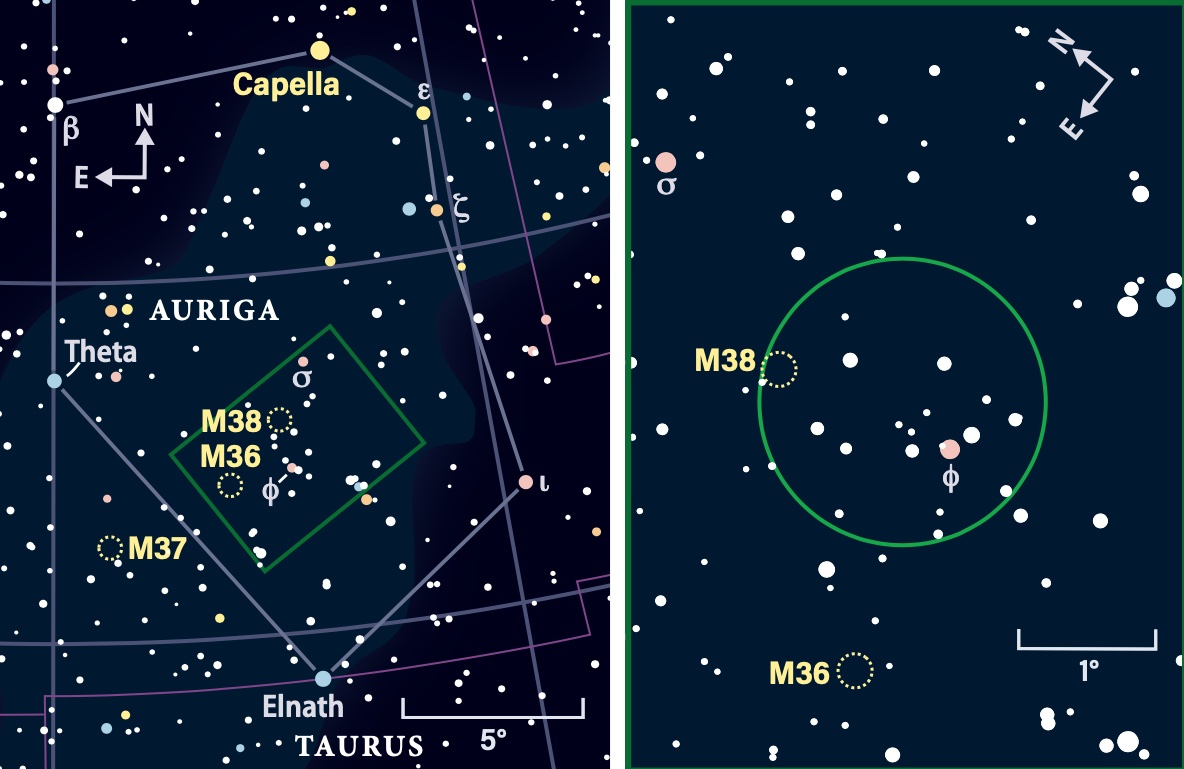

It’s a great time to view Uranus, nicely located in Taurus and high in the sky after sunset. Uranus lies south of the Pleiades star cluster (M45) and is easy to spot in binoculars, shining at magnitude 5.7. Look south of M45 for a pair of 6th-magnitude stars, 13 and 14 Tauri. Uranus wanders west of the pair and begins the month 22″ southwest of 13 Tau, the westernmost of the two suns. By Jan. 31, Uranus stands 47″ southwest of this star. The ice giant is visible most of the night, setting around 2 a.m. local time on the 31st. A gibbous Moon is in the vicinity on the 26th and 27th.

Through a telescope, Uranus reveals a pale greenish disk spanning 4″. Observers with experience in planetary high-speed video capture might want the challenge of recording Uranus while it is high in the sky soon after sunset.

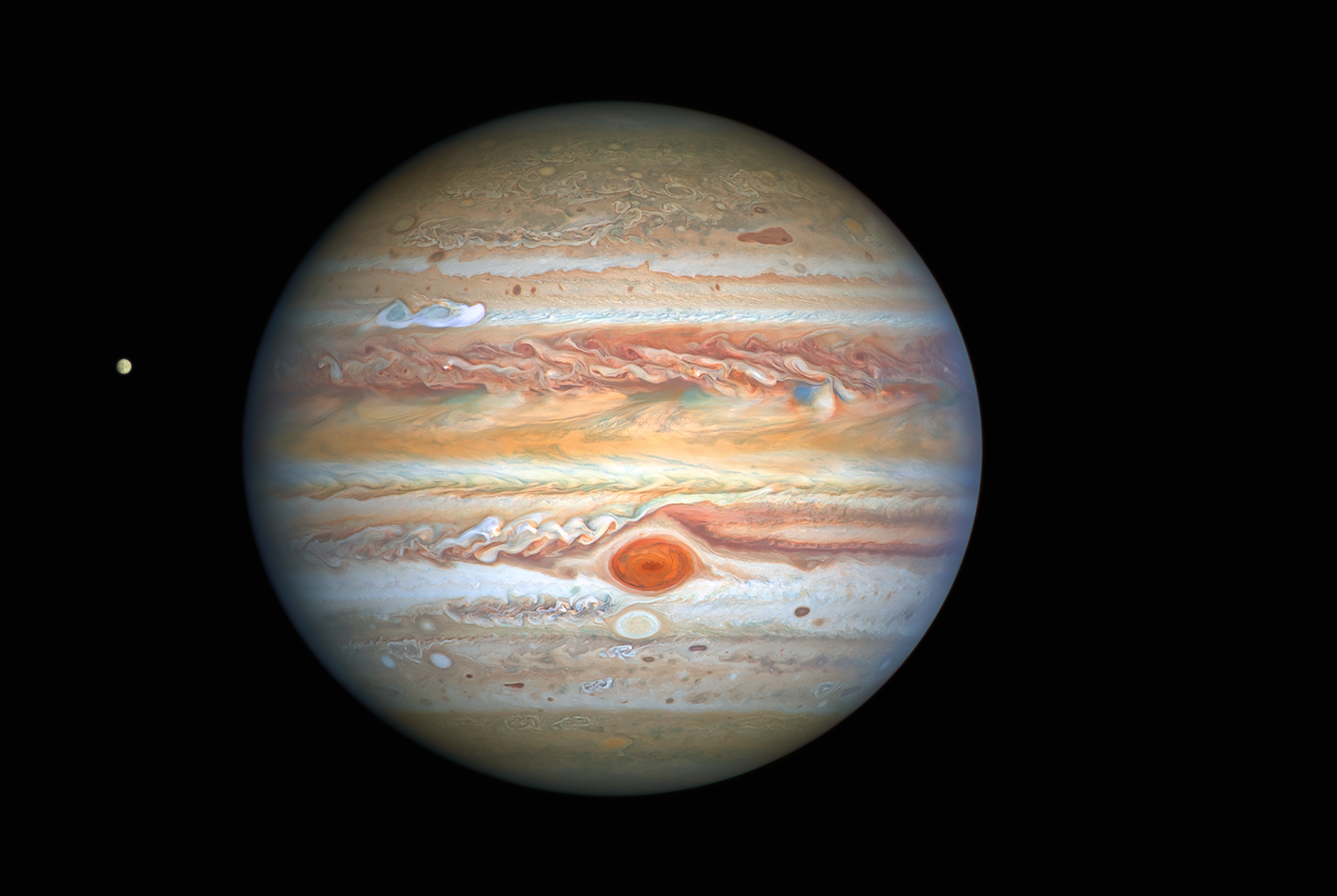

Jupiter, the solar system’s largest planet, reaches opposition Jan. 10. It’s up all night, shining at its maximum brilliance of magnitude –2.7. Jupiter is perfectly placed for Northern Hemisphere observers, located in Gemini the Twins and climbing above 60° in altitude before midnight.

Jupiter sports a 46″-wide disk, making atmospheric features visible in most telescopes. Two dark equatorial belts jump out immediately, and more patient viewers are rewarded with numerous shaded features — huge storms that are generated by turbulence caused as the equatorial and polar regions of the planet rotate at different speeds. The equatorial regions complete one rotation in 9 hours 50 minutes, and higher latitudes take five to six minutes longer, generating shear where they meet.

The Great Red Spot dominates the southern edge of the South Equatorial Belt. If it’s not visible early in the evening, try again a few hours later. With such long nights, you’re guaranteed a view of it every night, although some appearances are in the early morning.

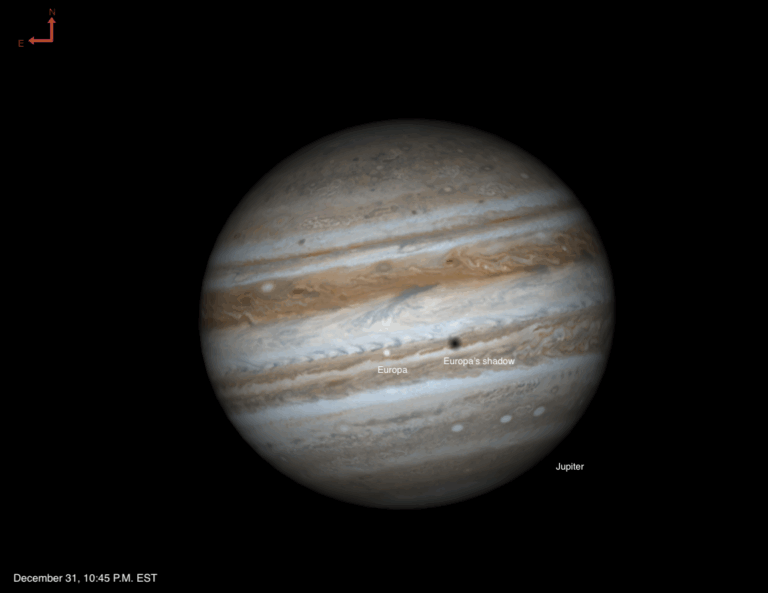

Jupiter’s four largest moons — Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto — dance around the planet with periods ranging from two to 17 days. You can watch them appear from and disappear behind the disk or cast shadows onto the cloud tops as they transit in front of the planet.

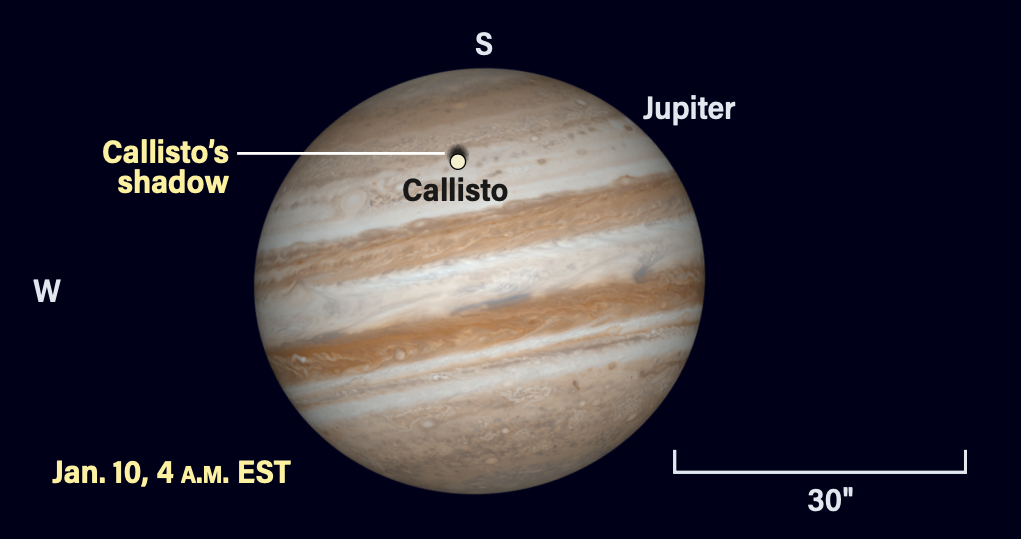

With Jupiter near opposition, there are some fascinating shadow transits early this month. Before opposition, the shadow always precedes its moon across the jovian disk. After opposition, the moon transits first, followed obediently by its shadow. This month we’re lucky to see Callisto transit the day of opposition, which means the moon overlaps its own shadow.

First, though, Callisto kicks off the month as it reappears from behind Jupiter Jan. 1 at about 9:02 p.m. EST. Its reappearance takes about 10 minutes. When do you first spot the moon at Jupiter’s northeastern limb?

Shadow transits get underway Jan. 5, as Io’s shadow takes a notch out of Jupiter’s eastern limb starting around 8:50 p.m. EST. Io reaches the limb six minutes later, at 8:56 p.m. EST. An hour later they’re central on the disk, and leave beginning around 11:05 p.m. EST as the shadow departs, followed by Io six minutes later.

Two events occur close together on Jan. 6. Ganymede orbits Jupiter farther out than Io, so its shadow leads the moon by 20 minutes. Make sure you’re watching the planet at 8:30 p.m. EST as Ganymede approaches the eastern limb. Io reappears from behind Jupiter beginning at 8:32 p.m. EST, and takes three minutes to fully emerge.

As Io moves away from the limb, Ganymede creeps closer. Starting at 8:59 p.m. EST, Ganymede’s shadow appears on Jupiter’s disk. By 9:09 p.m. EST the shadow is fully visible, and nine minutes later, Ganymede itself begins ingress. Watch over the next three hours as the pair transits, ending with the shadow leaving by about 12:24 a.m. EST (now the 7th in the Eastern time zone) and Ganymede moving clear of the disk by 12:45 a.m. EST.

Jan. 7 sees Europa in action, crossing the disk with its shadow. The shadow transit begins at 11:35 p.m. EST, followed by Europa seven minutes later. By midnight CST (1 a.m. EST on the 8th) the moon and shadow are central on the disk, with Europa more of a challenge to see against the bright background. The shadow transit ends by 2:30 a.m. EST, with Europa clear of the disk seven minutes later.

There’s a special treat Jan. 9/10 as Jupiter reaches opposition. Callisto transits Jupiter, overlapping with its own shadow because the illuminating source, the Sun, is directly behind us as we view the planet. The transit begins minutes before 2 a.m. EST on Jan. 10 (11 p.m. PST on the 9th). By 2:10 a.m. EST the transit is fully underway, and Callisto reaches the center of the disk by about 4 a.m. EST. Do you see any evidence of the shadow? Callisto may exhibit a darker southern edge, which is due to the shadow. The transit ends shortly after 6 a.m. EST.

On Jan. 12 we’re past opposition so when Io transits, this time its shadow trails the moon. Io begins its transit around 10:39 p.m. EST and its shadow follows about four minutes later. By 10:50 p.m. EST both are clearly visible on the disk. They reach midway an hour later.

Ganymede transits again Jan. 13/14, this time also with the moon leading. Ganymede reaches the disk at 12:34 a.m. EST (the 14th in EST only), followed by the shadow at 12:58 a.m. EST. The pair takes nearly three hours to cross Jupiter. Ganymede transits again on the morning of Jan. 21, starting at 3:51 a.m. EST. Its shadow now trails the moon by more than an hour, and appears at 4:58 a.m. EST.

This sequence shows off the changing illumination as Jupiter passes through opposition. Later this month, the moon-shadow separation further increases.

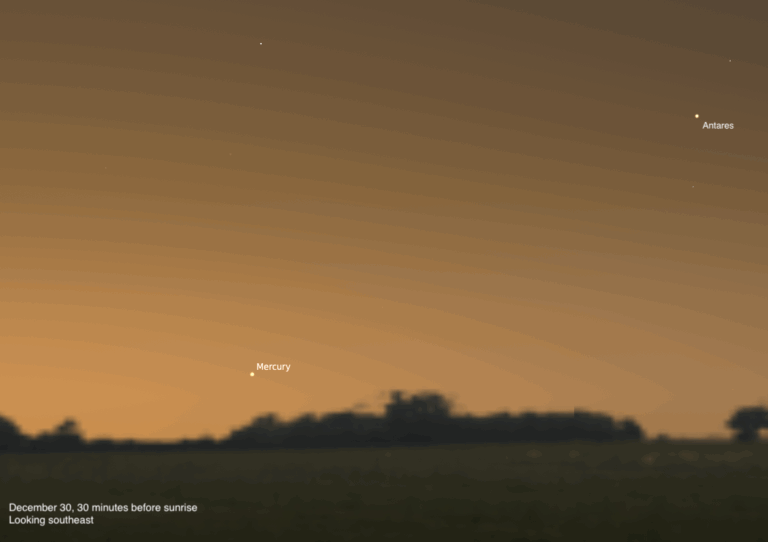

Mercury may be visible briefly the morning of the New Year, glowing at magnitude –0.6 and 2° high in the southeastern sky about 30 minutes before sunrise. With a clear horizon, you might spot it. The sky brightens quickly so the observing window is only a few minutes. After this, Mercury quickly heads toward its superior conjunction with the Sun on the 21st.

Venus reaches superior conjunction with the Sun Jan. 6 and Mars reaches conjunction with the Sun on the 9th. Neither of these planets is visible this month.

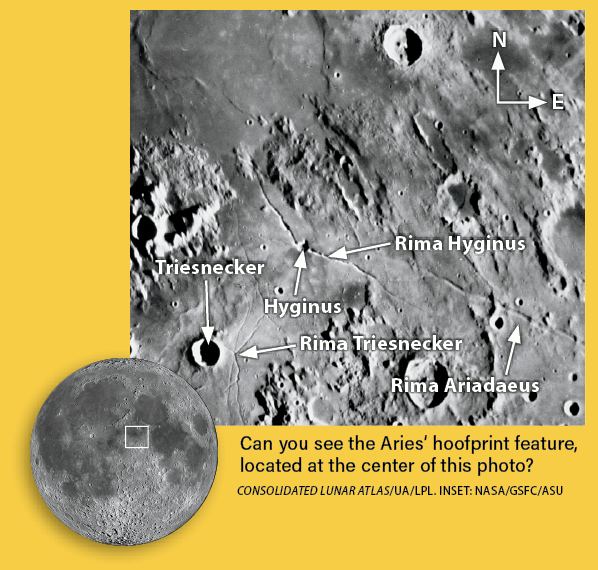

Rising Moon: Hoofing it across the ditch

Aries the Ram certainly did not step on the Moon, but it’s fun to imagine the large hoofprint on the lunar surface could be his doing. On the evening of the 25th, the Sun has risen over the fascinating Hyginus, Triesnecker, and Ariadaeus rille complexes. In this area just north of the equator, what catches the eye most is a delightful hoofprint-shaped feature. The combination of brightly lit mountains and two deep channels of extra-dark lava create this striking play of light and shade. The dazzling array of craters farther south along the terminator vie for attention, but the cracks and shapes draw us back.

It’s easy to understand why it is not labeled on the lunar maps — physically it is a just jumble of mountains left over from the giant Imbrium impact, with a channel on either side. Furthermore, lunar scientists focused on the fascinating Rima Hyginus with good reason, as it is almost surely volcanic in origin. Hyginus itself is a huge collapse pit, the biggest in a chain of smaller pits that sculpt the edges of a long-ago lava channel. It too stands out nicely because one wall is brightly sunlit while the other remains in shadow.

In the course of 24 hours, Aries’ hoofprint and the Hyginus rille become mere echoes of their magnificence under the increasing glare of the Sun. To see the region with reverse lighting, check it out late on the evenings of the 8th and 9th for the longest shadows.

For south pole Mount Clementine fans, zoom in from the 1st to the 5th to watch this fantastic area in 3D relief, and again as the calendar flips to February.

Meteor Watch: Only the brightest

The Quadrantid meteor shower is a regular on the calendar, active between Dec. 28 and Jan. 12. The parent object is asteroid 2003 EH1, likely the leftover core of a once-active comet. This year the peak coincides with a Full Moon, strongly depleting the number of visible meteors to only the brighter ones. The meteor stream is known to be narrow; the International Meteor Organization predicts the peak of the shower around 4 p.m. EST Jan. 3, with maximum activity for a few hours on either side of this time. This timing benefits observers in Asia.

In the U.S., the radiant rises shortly before midnight local time and by 4 a.m. it’s nearly 45° high. Rates will be reduced to well under a dozen per hour at the peak, and on the early morning of Jan. 3, U.S. observers will see fewer than this number. However, the Quadrantids are known to produce fireballs, which makes it an exciting shower to watch.

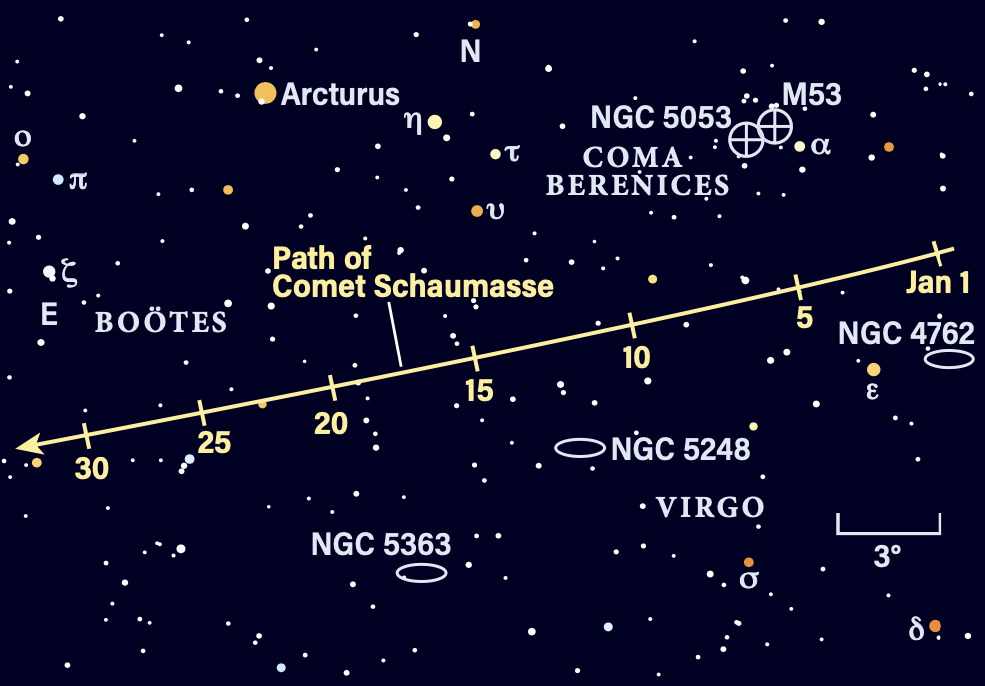

Comet Search: Night crawler

Dedicated cometophiles will be content with a modest telescopic target from a dark site. Comet 24P/Schaumasse should be glowing green from diatomic carbon emission throughout this perihelion passage, now 1.2 astronomical units (AU) from the Sun. (One AU is the average Earth-Sun distance.) This will make a nice contrast to the white glow of background galaxies as it exits the Virgo Cluster region. Patience and planning are required — you’ll need enough energy to be alert at 2 a.m.

Despite several returns since its discovery in 1911, Schaumasse’s peak brightness is forecast in a wide range from 8th to 12th magnitude. Part of the uncertainty is that it has been known to have strong enough jet activity to modify its orbit. Take a close look at medium to high power along the east flank, where that jet should make a sharp leading edge with a soft, fading shallow fan to the west and north.

Once Schaumasse has faded in a couple of months, its awkward 8.2-year period gives us poor return geometries until 2059, when it gets as close to Earth as 0.3 AU and shines near 6th magnitude.

South of the equator, observers are treated to the bright binocular comet C/2024 E1 (Wierzchoś) rising into the deepening evening twilight after midmonth. At perihelion on the 20th, it may surge beyond the expected 5th magnitude.

Locating Asteroids: Psyching out the Bull

First-magnitude Aldebaran commands the eastern sky, a snap to get to and perhaps the last of the stars in your align process. Curling just above Taurus’ ruddy eye is the 16th asteroid to be discovered, 16 Psyche, yours to see with a 3-inch scope from the suburbs at medium power.

With just two field sketches you can track Psyche’s movement for the entire month. Early in the month, locate the zigzag of 8th- to 9th-magnitude stars just northeast of Aldebaran and place them at the bottom of one circle. Next, drop a few fainter 10th-magnitude dots half a field north — one of these will be the target. Return to see which has moved.

Later in the month, look due north of Aldebaran and follow a gentle curve of stars that hooks toward the northeast. Those last three are your anchor. On the 10th, the 173-mile-wide, potato-shaped metallic space mountain is the slightly fainter component of a temporary “double star” with the end of the hook.

Just three short years from now, we’ll get close-up views from an orbiting NASA spacecraft. Psyche is going to be very different from Ceres or Vesta — exciting!

Star Dome

The map below portrays the sky as seen near 35° north latitude. Located inside the border are the cardinal directions and their intermediate points. To find stars, hold the map overhead and orient it so one of the labels matches the direction you’re facing. The stars above the map’s horizon now match what’s in the sky.

The all-sky map shows how the sky looks at:

9 p.m. January 1

8 p.m. January 15

7 p.m. January 31

Planets are shown at midmonth