To me, it’s the same when we compare the apparent sizes of Full Moons. Because the Moon’s orbit isn’t circular, a Full Moon can occur when the Moon is as far from Earth as it can get (apogee), or when it is as close as possible (perigee). A perigee Full Moon can be as much as 14 percent larger than an apogee Full Moon.

And here’s my gripe. In recent years, news stations (usually via the weather reporter) refer to a perigee Full Moon as a “Super Moon.” Astronomically naïve listeners rush outside, expecting to see a Full Moon filling the night sky. Instead, they see the same old ordinary Full Moon. And I’m with them. I’ve never noticed an obvious difference in the sizes of various Full Moons — not when they occur a month apart. Now, if you place an apogee Full Moon and perigee Full Moon side by side (something we can do photographically), the difference is obvious.

Here’s my suggestion to the media: Don’t refer to a perigee Full Moon as a “Super Moon.” Call it what it is — a “larger-than-average Full Moon.” Sadly, the idea will never fly. Not enough hyperbole.

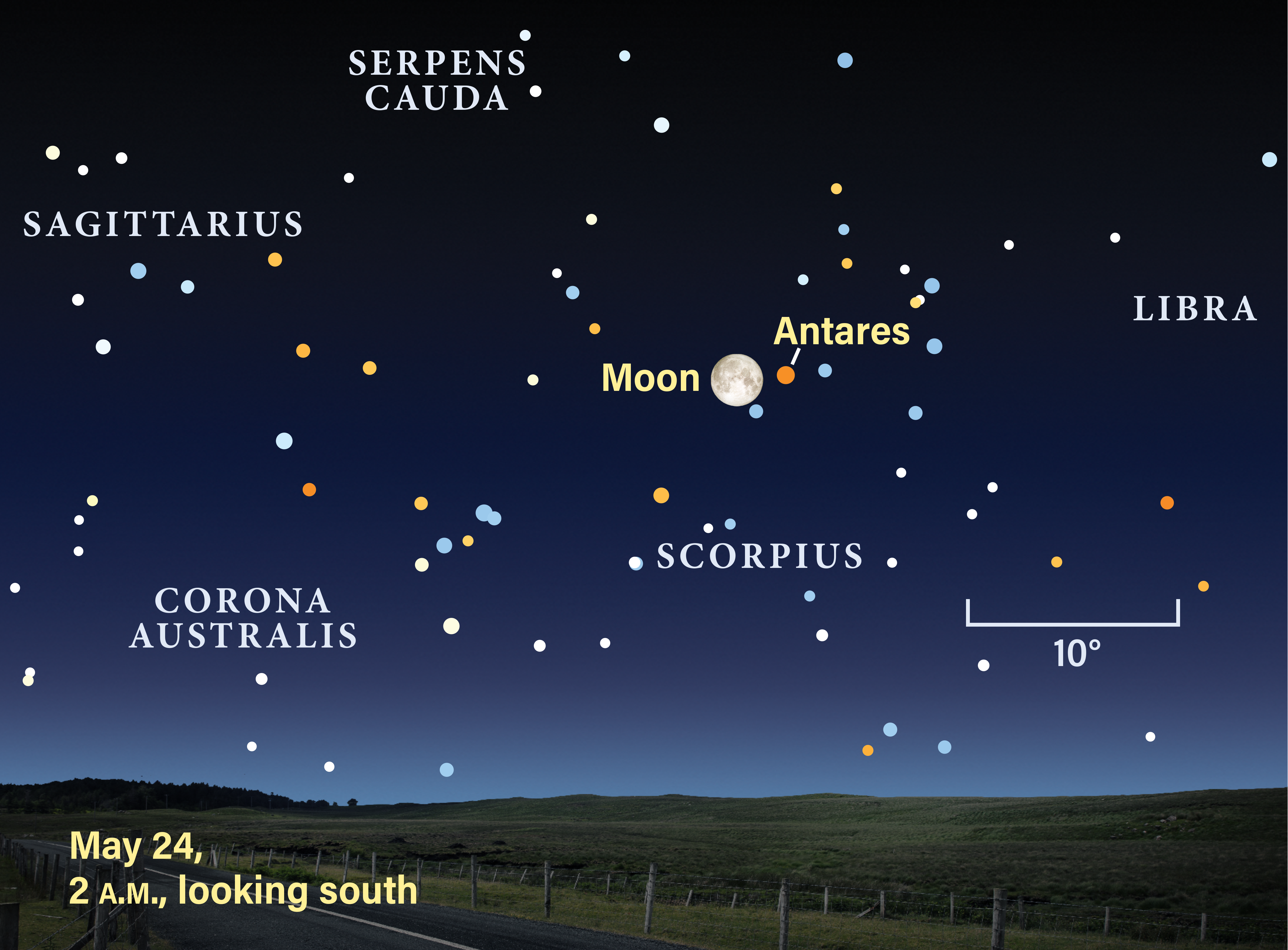

Although the eclipse will last more than five hours, you can skip the first and last hours when the Moon encounters the penumbra (the faintest part of Earth’s shadow). Things get interesting with the onset of partiality at 10:34 p.m. EST as the Moon enters the umbra (the dark part of the Earth’s shadow). Totality begins at 11:41 p.m. and ends at 12:43 a.m. Die-hards will stay on to view the closing partial phases, which last until the Moon leaves the umbra at 1:51 a.m. By the way, binoculars or a telescope are optional. As with any total lunar eclipse, this one can be enjoyed with the unaided eye.

There are several reasons why people may opt out of this eclipse. It occurs at what is to many East Coast residents an ungodly hour, evening temperatures in northerly latitudes might be bone-chilling, and veteran skywatchers may harbor an “if you’ve seen one, you’ve seen ’em all” attitude. Don’t let these excuses deter you from viewing this eclipse!

A total lunar eclipse is hardly a nightly event. The next one won’t happen until May 26, 2021, and that one will only be visible from regions around the Pacific Ocean. Upcoming total lunar eclipses viewable from North America will occur on the evenings of May 15/16, 2022 (best seen in eastern locales) and November 8, 2022 (better viewed farther west). The next all-North America total lunar eclipse won’t happen until March 13/14, 2025. Considering the possibility of cloudy weather on any eclipse night, it may be years before you see your next total lunar eclipse. If you absolutely need your beauty sleep, at least set your alarm clock for mid-eclipse (12:12 a.m. EST) for a quick view of the totally eclipsed Moon.

What about the possibility that Jack Frost may be nipping at your nose? Not to worry! No one says you have to stand outside in the snow for hours on end to capture every second of the eclipse. Every 10 to 15 minutes, bundle up and go outside for a quick peek.

And lose that “been there, done that” attitude! During a typical total lunar eclipse, the Moon takes on the eerie coppery red color that must have frightened pre-civilized humans. This “Blood Moon” results from the same refractive effect that causes the setting Sun to appear reddish and fills the umbra with a similar ruddy hue. Excessive cloudiness, dust from forest fires and desert wind storms, and ash from volcanic eruptions can change the rules. Depending on the condition of Earth’s atmosphere, a totally eclipsed Moon can appear unusually bright or so dark it is nearly invisible. We never know exactly how the fully eclipsed Moon will look.

Scribble in “Total Lunar Eclipse — Night of January 21/22” on that magnetic whiteboard you keep on your refrigerator. This time when people rush outside to see a “Super Moon,” they’ll truly be greeted by a super Moon!

Questions, comments, or suggestions? Email me at gchaple@hotmail.com. Next month: An in-depth look at the Orion Nebula. Clear skies!