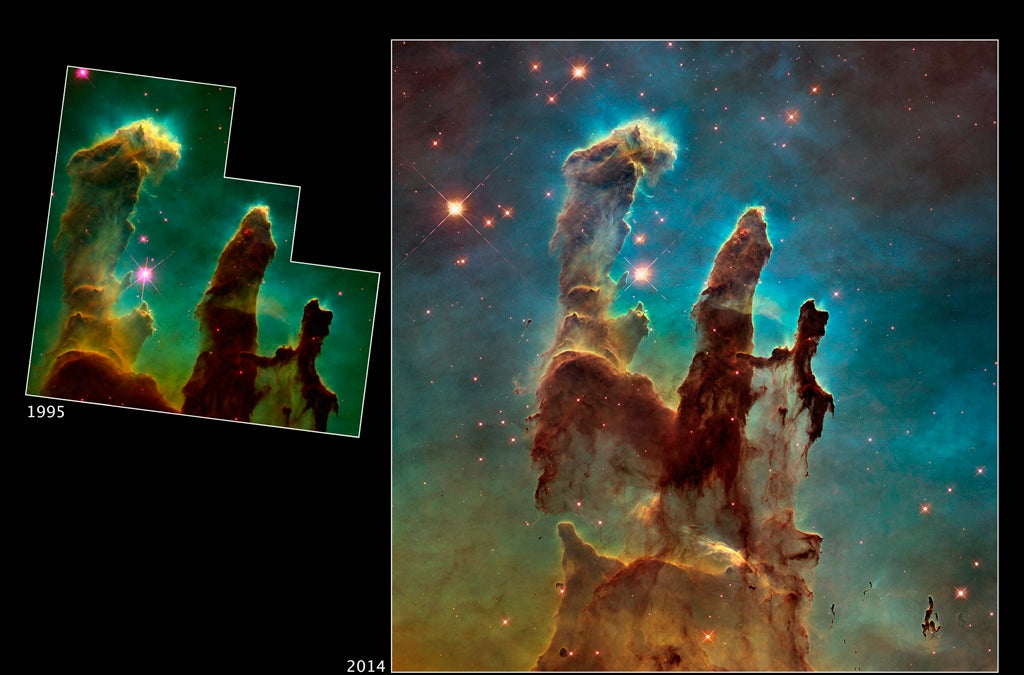

The Hubble Space Telescope’s iconic image of the Eagle Nebula’s “Pillars of Creation” heralded the instrument’s rebirth in 1995 and showed the public just how incredible astrophotography could be above Earth’s atmosphere. “No one imagined a reaction that would turn the image into a cultural icon,” Astronomy Contributing Editor Jeff Hester – who actually took the photo – said in April’s Hubble commemorative issue. The image has graced everything from U.S. postage stamps to classroom posters.

And yet the Pillars of Creation might not even exist anymore. NASA captured this stellar nursery at a fleeting moment. The region is packed with gas and young stars. And as those stars ignite, the gases evaporate into space, as seen in the green streaks that surround the columns. But because the nebula sits some 7,000 light-years from Earth, the light we see left the nebula 7,000 years ago, as agriculture spread across Europe. Intense ultraviolet radiation from young stars has stripped much of the gas since that time.

We’re already starting to see the signs of that destruction. NASA revisited the Eagle Nebula last year and this time took images in the near-infrared part of the light spectrum as well as the visible.

The view pierced the dust and revealed the pillars’ tenuous true nature as well as infant stars hidden among the gas. One prominent jet, perhaps from another forming star, has already increased its reach some 60 billion miles (97 billion kilometers) farther into space. And scientists suspect that a nearby supernova, like the one thought to have brought our solar system radioactive elements, might have already ablated what was left of the gas. Spitzer Space Telescope images show the supernova’s shock wave was racing at the pillars 6,000 years ago. We should know for sure in a couple thousand years.

Associate Editor