Key Takeaways:

- Comet C/2023 A3, formally designated Tsuchinshan-ATLAS, was independently discovered in early 2023 by the Purple Mountain Observatory in China and the Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System (ATLAS) in South Africa.

- This celestial object from the outer solar system reached its closest point to the Sun (perihelion) on September 27, 2024, followed by its closest approach to Earth on October 12, 2024.

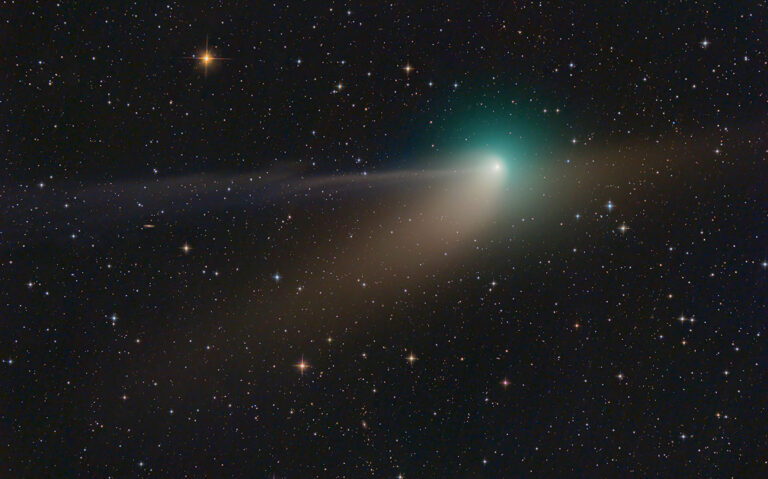

- The comet offered extensive naked-eye visibility, achieving a peak brightness of magnitude –4.9 in the Northern Hemisphere, and exhibited a prominent tail stretching up to 15 degrees, alongside a notable anti-tail.

- Distinguished by its predictable performance, Tsuchinshan-ATLAS will not return to the inner solar system for approximately 80,000 years, highlighting the rarity of such bright cometary appearances.

Comets are notoriously unpredictable. Some of the most spectacular of these icy visitors pop up unexpectedly, careening toward the Sun and bursting out in spectacular fashion with little advance notice. Others are spotted over a year before they make their closest approach, but break apart and fizzle out.

Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS was the rare comet that arrived with a year and a half of fanfare and lived up to the hype, serving up naked-eye views for weeks. If it was not a Great Comet, it was at least a very, very good one.

Formally known as C/2023 A3, this ice ball from the outer solar system was first discovered in images taken Jan. 9, 2023, by a telescope operated by Purple Mountain Observatory near Nanjing in China’s Jiangsu Province. A month and a half later, it was identified by a telescope in South Africa belonging to the Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System (ATLAS). These observations put the object at 670 million miles (1.1 billion kilometers) from the Sun, between the orbits of Jupiter and Saturn.

It wouldn’t reach perihelion — its closest point to the Sun — until Sept. 27, 2024. But immediately, the gears of the hype machine began turning.

Initially, it appeared that the best views could wind up being exclusive to the Southern Hemisphere. The comet first became visible in the southern predawn sky, and remained low in the northern sky as it reached perihelion. Soon after, it moved into conjunction with the Sun and was lost in our star’s glare. But the best views were yet to come: The comet reemerged as an easy naked-eye evening object around the same time it made its closest approach to Earth on Oct. 12. At its peak, it was recorded as bright as magnitude –4.9, the brightest in the Northern Hemisphere since 1997’s Hale Bopp (C/1995 O1). Tsuchinshan-ATLAS also sported a stunning tail stretching up to 15° in photographs, plus a stark anti-tail.

Comets being what they are, there’s no telling when one this bright will swing by next. Until then, we have these images to savor.

What’s in a name?

Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS owes its name to two observatories that discovered it independently. The first, Purple Mountain Observatory (PMO), was founded in 1934 and is considered China’s first modern astronomical observatory. The name Tsuchinshan — traditionally used for comets discovered by PMO — is an older transliteration of Zijinshan, which is Chinese for “purple mountain.” The observatory’s historic location is atop a mountain in the heart of Nanjing, a city of nearly 10 million people.

The Minor Planet Center’s code for the observatory is Nanking — the historic transliteration of Nanjing. But the bulk of PMO’s research is now conducted at several satellite observatories at more remote sites. The telescope that first detected Comet C/2023 A3 is a 1.2-meter Schmidt located in Xuyi County, roughly 30 miles (50 kilometers) northwest of PMO’s original site. The Xuyi station reported three detections of the object over a single night, but it was subsequently presumed lost.

The Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System (ATLAS) is an network of four telescopes operated by the University of Hawai’i and funded by NASA that scans the entire sky in search of asteroids that could threaten Earth. Two ATLAS scopes are in Hawaii, one is in Chile, and one is in South Africa. The latter — a 0.5-meter Schmidt at the South African Astronomical Observatory in Sutherland — is the one that independently detected Comet C/2023 A3, on Feb. 22, 2023. Subsequent analysis revealed that it was the same object discovered by PMO.