Father Kemble loved observing through binoculars and telescopes. His most enduring astronomical legacy revolves around a curious asterism. He bumped into it more than 20 years ago while scanning the faint constellation Camelopardalis the Giraffe with his 7×35 binoculars. Camelopardalis occupies the seemingly starless void between Auriga and Ursa Minor.

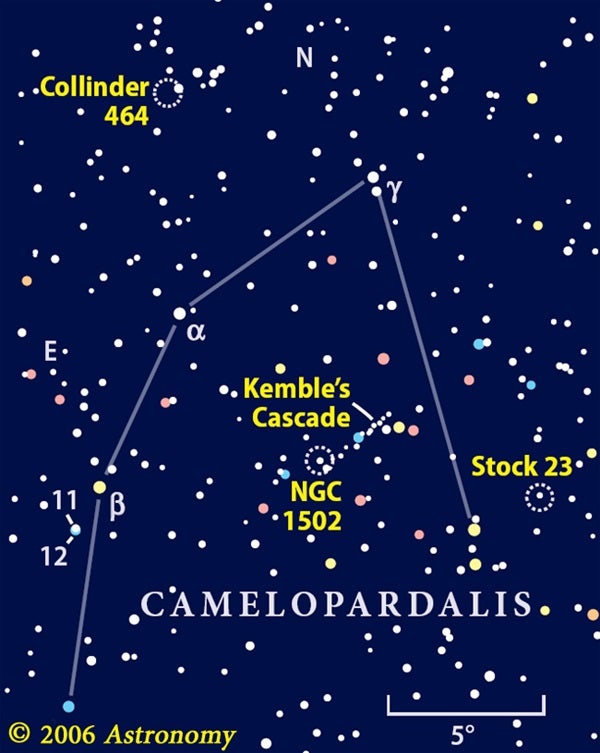

After you locate Kemble’s discovery, it will help make the Giraffe’s dim outline stand out. Aim your binoculars halfway along a line from Capella to Polaris, and look for the 4th-magnitude stars Alpha (α) and Beta (β) Camelopardalis. Before moving on, look south of Beta Cam for a pretty double star formed by 5th-magnitude 11 Camelopardalis and 6th-magnitude 12 Camelopardalis. The stars lie 3′ apart, making them easy prey for 7x binoculars.

Now scan approximately 6°, or about a full binocular field, west of Alpha and Beta. Watch for a stream of 14 faint stars shining between 7th and 9th magnitudes flowing southeastward and accented by a lone 5th-magnitude sun about midway. This is Kemble’s Cascade, a name bestowed on the grouping by famed deep-sky author Walter Scott Houston. Although the stars in this 2.5° string are not physically related to each other in space, they seem to line up with almost military precision.

If you head southeastward along the cascade, you should spot a dim blur next to its last star. That’s open cluster NGC 1502. Father Kemble likened the view to a waterfall pouring into a pool. The 45 stars that call NGC 1502 home collectively shine at 6th magnitude. My 10×50 binoculars resolve only a few individual points, however; the rest combine to make a triangular glow.

Our final target is Collinder 464, another little known open cluster. You’ll find it about 8.5° northeast of Alpha Cam. Although the 50 suns that form Collinder 464 are difficult to distinguish from the surroundings, I’ve always been impressed by a 1° x 2° pattern of 10 stars that includes some from the cluster as well as a few to its north. I always see the stars as a toy poodle’s profile. I’ve christened this asterism “Amy” after my own toy poodle. To my eyes, the dog is facing west with her legs extending to the south and her tail standing at attention to the east. The stars that mark the tip of her nose, ear, and tail look slightly orangish, while the others appear white.

Have a favorite binocular asterism of your own? I would love to hear about it. E-mail me here.

Next month, we return to mighty Orion, my favorite constellation. And remember, when it comes to skywatching, two eyes are better than one!