The first evening of June finds Mars in the company of a lovely crescent Moon. The Red Planet reached opposition back in January and has faded considerably since then, glowing now at 1st magnitude.

Mars spends the month moving eastward against the backdrop of Leo the Lion. It shares a small patch of sky with Leo’s brightest star, 1st-magnitude Regulus, in mid-June. The two meet on the 17th, when the planet passes less than 1° north of the star. Be sure to compare the ruddy color of Mars with Regulus’ blue-white hue.

Alas, Mars now lies on the opposite side of the Sun from Earth and appears only 5″ across when viewed through a telescope. Even large amateur instruments will struggle to show any surface details.

You might catch a glimpse of Jupiter low in the northwest during evening twilight in early June. On the 1st, it glows at magnitude –1.9 and lies about 5° high 45 minutes after sunset. It soon disappears in the twilight glow as it heads toward solar conjunction June 24.

As Jupiter exits the evening stage, Mercury makes a grand entrance. The innermost planet climbs a bit higher in the northwest with each passing day, and by June 30 stands 10° high an hour after sunset. It shines at magnitude 0.3 and appears obvious in the deepening twilight. Don’t confuse Mercury with the similarly bright star Procyon, which lies 20° to the planet’s left.

Point a telescope at Mercury and you’ll see a half-lit disk that spans 7″. Its phase will wane and its size will grow during the first half of July.

Once Mars sets, you’ll have to wait a few hours for the other two naked-eye planets to appear. First up is Saturn, which rises around 2 a.m. local time in early June and some two hours earlier by month’s end. The ringed planet shines at magnitude 1.0 among the faint background stars of southern Pisces the Fish.

If you’ve been watching Saturn through a telescope these past few months, you’ll have noticed that the rings have started to open. In mid-June, they span 39″ and tilt 3.4° to our line of sight. The narrow tilt means that the rings don’t reflect as much light in our direction as they normally do, making the planet’s satellites easier to see. In addition to 8th-magnitude Titan, which shows up through any instrument, keep an eye out for the trio of 10th-magnitude moons: Tethys, Dione, and Rhea.

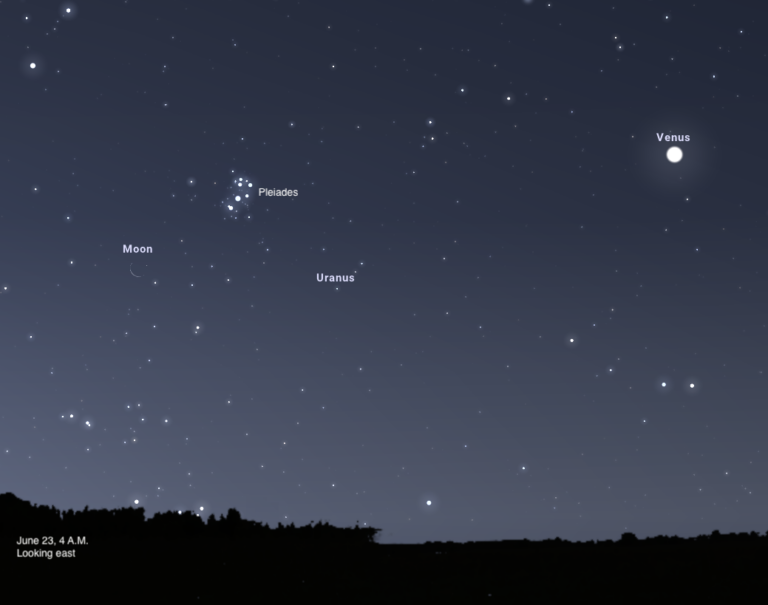

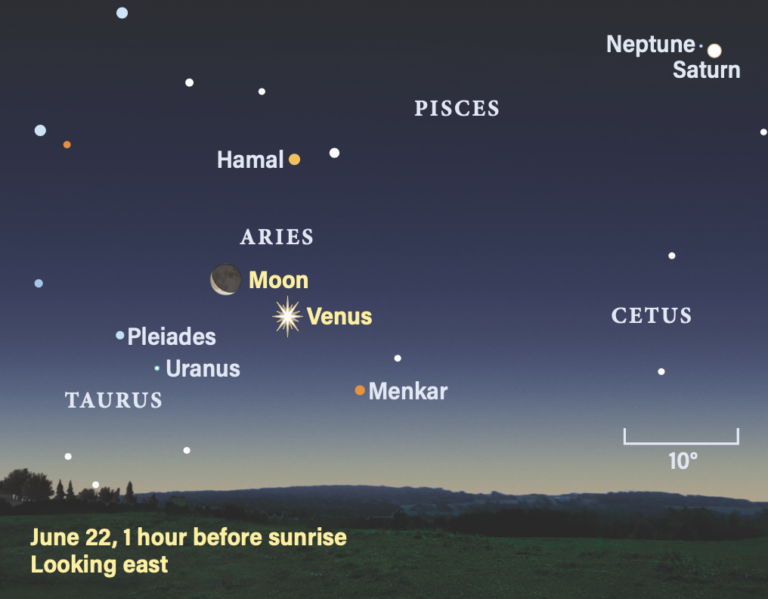

The final planet to appear on these June nights is also the most dazzling: Venus. The brilliant planet rises between 3 a.m. and 4 a.m. all month. Shining brighter than magnitude –4.0 this month, Venus outshines every other celestial object except for the Sun and Moon. The planet moves eastward relative to the background stars during June. It starts the month in Pisces, briefly traverses a corner of Cetus, and then crosses Aries before entering Taurus at month’s end.

Venus reaches greatest elongation June 1, when it lies 46° west of the Sun and stands 30° high in the northeast an hour before the Sun rises. At greatest elongation, the planet’s disk appears 24″ across and half-lit when viewed through a telescope. At the end of June, Venus spans 18″ and shows a 63-percent-lit phase.

A nearly Full Moon occults the 1st-magnitude star Antares on June 10. Prime viewing locations include Australia and New Zealand. From Sydney, Antares disappears behind the Moon’s western limb at 9h24m UT and reappears at the eastern limb at 10h40m UT. The corresponding times for Brisbane are a little earlier, at 9h16m UT and 10h30m UT.

The Starry Sky

As twilight fades these June evenings, the southern sky provides a magnificent tableau. Crux the Cross sits due south with the Pointers (Alpha [α] and Beta [β] Centauri) to its left. On the opposite side — to the west — lies a rich region in the vicinity of Eta (η) Carinae. Among these stars appears a character that Dutch-Flemish astronomer Petrus Plancius introduced more than 400 years ago. Alas, Polophylax, whose name means watcher or guardian of the pole, did not last long as a constellation.

Andrea Corsali was the first European to depict the Cross. He drew a crude map of this region in 1516 that showed it as it would appear from outside the imaginary celestial sphere, a common practice at the time. Although the stars are far from being in their exact positions, the Cross is easy to see and two bright stars to its right appear to be Alpha and Beta Cen.

Corsali drew a group of stars on the Cross’ other side that does not correspond strongly with the actual stars in this area. If you think in more forgiving terms, however, Corsali simply may have portrayed some scattered stars in eastern Carina even less precisely than he did the Cross and the Pointers.

Plancius, relying on Corsali’s drawing, appears to have interpreted these stars as having the shape of a standing person, Polophylax, and drew such a figure on his 1592 and 1594 maps. Interestingly, Plancius placed the Cross and Polophylax incorrectly — a long way from Centaurus and on the opposite side of the South Celestial Pole.

The end of the pole’s guardian came a few years later, when Plancius had access to Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser’s far better observations. I find this sad because Plancius made him look quaint, dressing him in a blue cloak.

Star Dome

The map below portrays the sky as seen near 30° south latitude. Located inside the border are the cardinal directions and their intermediate points. To find stars, hold the map overhead and orient it so one of the labels matches the direction you’re facing. The stars above the map’s horizon now match what’s in the sky.

The all-sky map shows how the sky looks at:

9 p.m. June 1

8 p.m. June 15

7 p.m. June 30

Planets are shown at midmonth