When writing about the consequences of viewing the Sun directly with a telescope, I used to relate the story of Galileo, who conducted solar observations at sunrise or sunset when the Sun’s brilliance was reduced. Supposedly, the practice led to Galileo’s blindness later in life. But there is compelling evidence that the story isn’t accurate. According to research by scholars such as Andrew T. Young, an adjunct faculty member of San Diego State University’s astronomy department, Galileo’s late-life blindness was most likely a result of cataracts brought on by complications from rheumatoid disease.

Whatever the cause of Galileo’s blindness, I would never recommend looking directly at the Sun with or without a telescope — not when it’s rising or setting, and not even when it’s veiled by a thick haze. Fortunately for Galileo, he soon learned that he could use a telescope to project the Sun’s image onto a sheet of paper.

Four centuries later, solar projection remains a primary way to view our home star. After placing a low-power eyepiece in your telescope and aiming at the Sun (use the telescope’s shadow, not the finder scope), hold a sheet of white paper about a foot from the eyepiece. Focus the projection until the circle of light (the Sun’s disk) appears sharp at the edges.

Sun projection may not threaten your vision, but it puts your telescope — particularly the eyepiece — at risk. Don’t use an expensive eyepiece. The adhesive holding the elements together could “cook,” ruining the eyepiece.

For eye (and eyepiece) safety, try a solar filter. Secured to the front of the tube, it reduces the amount of sunlight that enters the telescope and filters out harmful ultraviolet and near-infrared radiation, which allows you to view the Sun directly and safely. Solar filters tend to be pricey — running anywhere from $30 to $180, depending on the supplier and size needed to fit your telescope. There are many reliable suppliers, including Thousand Oaks, Orion, and Celestron.

Many inexpensive telescopes manufactured in the latter half of the 20th century came with solar filters that screwed into the eyepiece. I always warn people not to use such filters, as they can shatter due to the buildup of solar heat. If you’ve survived a near-mishap with such a filter, I want to know. Please, first-person ac-counts only. I don’t want to hear about your third cousin’s best friend whose barber knows someone whose screw-in solar filter cracked during use.

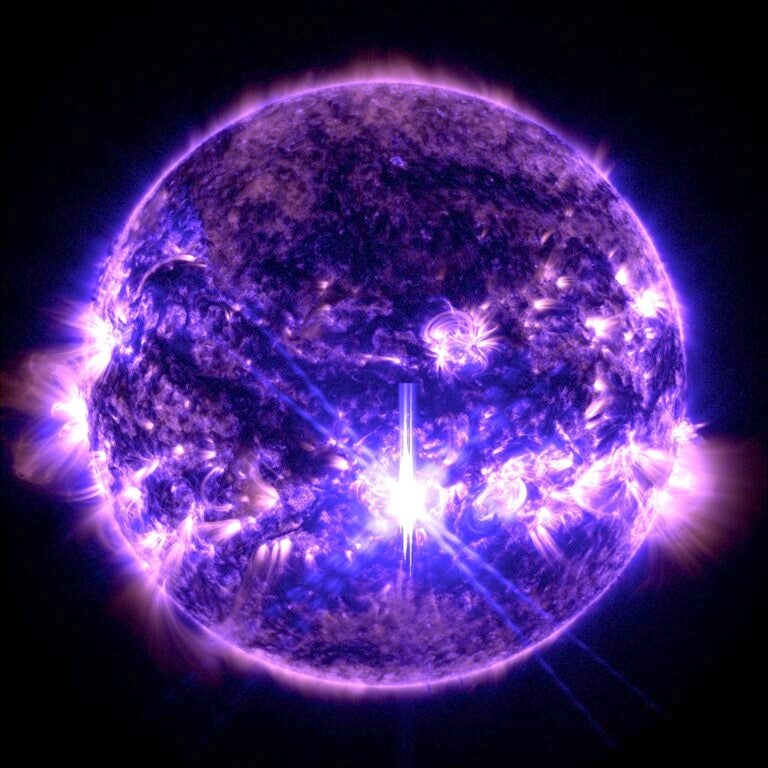

By using the appropriate equipment, you can repeat Galileo’s historic sunspot observations. The great astronomer discovered that sunspots are a transient phenomenon, appearing suddenly and then just as abruptly fading away. He correctly noted that they are surface features concentrated in a zone centered on the Sun’s equator. Long-lasting sunspots led to a rough determination of the Sun’s rotation, which Galileo equated to be the length of a lunar month.

As you try some sunspot observations of your own, please remember: Never, ever look directly at the Sun with your telescope! Oh, and yes, be sure to eat your vegetables, and get plenty of sleep.

Questions, comments, or suggestions? E-mail me at gchaple@hotmail.com. Next month: We look at the first double star and embark on an exciting International Year of Astronomy project. Clear skies!

June 2009: An imperfect Moon

See an archive of Glenn Chaple’s observing basics