If you live in the Northern Hemisphere, you may have noticed that the skies at dusk and dawn have been unusually striking since August 2008. Twilight’s once soft cerulean glow is now more luminous, as if glazed with frost. The consoling orange band that used to hug the horizon about 15 minutes after sunset has been replaced with a diffuse, incendiary glow that gives way to robust hues of yellow, rose, and purple higher up. Deep twilight colors have become warmer and more intense.

You also may have noticed crepuscular rays (the rosy fingers of dawn and dusk) now appear more frequently as cloud shadows scratch their long blue fingers across twilight’s pink sky — sometimes all the way to the opposite side of the sky. These strange twilight effects also arrive earlier in the east be-fore sunrise and linger longer in the west after sunset, causing high points on the opposing landscape (like mountain peaks or trees) to reflect a brilliant red light, especially in photos. What’s going on?

It’s a blast!

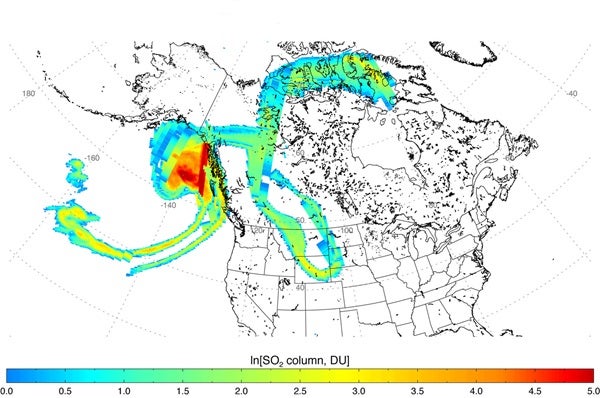

On August 7, 2008, Kasatochi, a small 1,000-foot-high (300 meters) island volcano in the Aleutians in southwestern Alaska, exploded without warning. The eruption sent ash and other volcanic particles 8.5 miles (13.7 kilometers) high. Preliminary reports reveal the volcano also injected about 1.5 million tons of sulfur dioxide into the stratosphere. The sulfur dioxide greenhouse gas should interest you as a skygazer.

Unlike ash, which soon falls back to Earth, sulfuric acid aerosols stay in the stratosphere for years. (Roughly one-third of the aerosols settle out each year.) This contaminant effectively reflects, scatters, and absorbs sunlight. To the visual observer, this means an overall reddening of the sky.

The reddening is especially enhanced during twilight because of the longer path light must take through the atmosphere to reach our eyes. As stratospheric winds disperse the aerosols, more and more people see the effects. To date, people are reporting the spooky effects from Finland to Hawaii. Because Kasatochi is a northern polar volcano, it is unlikely the effects will reach the Southern Hemisphere.

Light and shadow

Long-time sky photographer Doug Zubenel of Johnson County, Kansas, has been monitoring the Kasatochi color show since August 22. He has supplied me with a detailed report worthy of note. Perhaps you’ll recognize some of the strange twilight phenomena he describes.

As the twilight deepened, Zubenel saw a golden-yellow light begin to fill the western sky to an altitude of 50°. The light, which was centered on the Sun’s position, eventually faded, “but it lasted far longer than an ordinary twilight would at this time of day and year,” he notes.

Zubenel suspected volcanic aerosols, although he did not learn about Kasatochi’s eruption until August 25. That night, while setting up his camera at Kill Creek Park in Kansas, he documented another amazing effect. As the color show unfolded, the glow’s upper edge appeared unusually straight and parallel to the horizon, cleanly dividing the luminous aerosol cloud in the west from the darker sky above it.

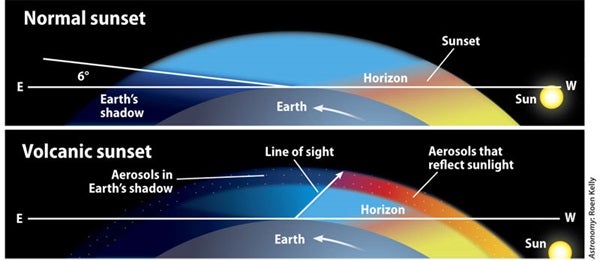

Zubenel shared his observations and photographs with Les Cowley at Atmospheric Optics (www.atoptics.co.uk). After looking at the geometry of the situation, Cowley confirmed Zubenel had seen Earth’s shadow in the west after sunset! We commonly see Earth’s shadow rising as a dark band in the east after sunset. As Earth rotates, that band rises until it reaches an altitude of about 6°, when it blends into the darkening sky background and fades from view.

But when volcanic ash fogs up the stratosphere, we can see Earth’s shadow against the glowing aerosol layer in the west after sunset, as shown in the diagrams on page 18. As Earth rotates, more and more of the thin aersol layer falls into Earth’s shadow, which seems to “push” the sunlit portion lower toward the western horizon until the shadow “snuffs” it out.

How long?

How long will the Kasatochi twilight displays last? According to the July 2008 Bulletin of the Global Volcanism Network, Kasatochi’s stratospheric aerosol cloud was one of the largest since the 1991 Mount Pinatubo eruption in the Philippines. So abnormal twilights may be with us for some time. Note, however, that while the intensity of the displays starts out strong, it generally softens as stratospheric winds disperse the gases.

yellow-ocher light whose upper portions turn rose, then purple, as twilight deepens. “Ultimately,” he says, “the purple and rose colors fade into the encroaching night, while the yellow deepens to orange lower down. Some 30 minutes after sunset, all that’s left is a reddish-orange horizon band that turns red before it fades from view.”

The colors were still strong at times in early February, though somewhat muted. By the time you read this article, these effects may have weakened further. But Kasatochi is not the only sulfur-rich volcano that has come to life in recent years.

For instance, on November 3, 2008, a volcanic eruption in the Afar region of Ethiopia expelled a large sulfur dioxide cloud (100,000 tons) that spread across the Arabian Peninsula and northern India in just 2 days. And who knows what sulfur-rich volcanic action tomorrow will bring? What’s important is that you keep an eye on the sky and be aware. As always, send your reports to me at someara@interpac.net.

April 2009: Searching for shadow bands

See an archive of Stephen James O’Meara’s secret sky