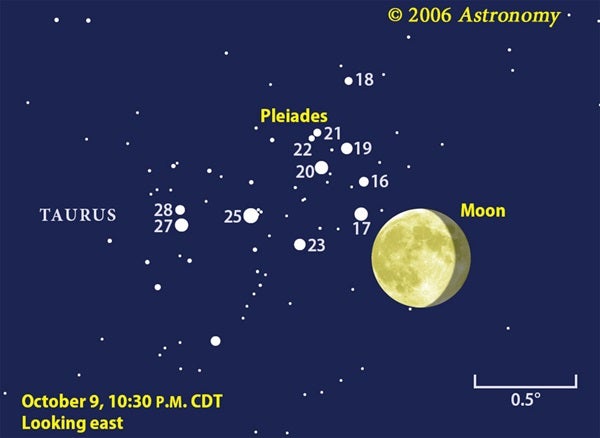

In quick succession around midnight EDT (9 P.M. PDT), you can watch a handful of bright stars disappear on the Moon’s illuminated limb, and a couple of dozen stars with a range of magnitudes pop into view on the dark lunar limb. The sequence of events appears slightly different everywhere. You can find exact times for your area on the Internet at lunar-occultations.com/iota. Observers on the West Coast will need a clear northeastern horizon to experience the first half of the show.

If you’re lucky, the Moon will graze one of the brighter Pleiads. You might see a star wink out and reappear several times in quick succession as mountains and valleys on the lunar limb pass it by. Astronomers at the International Occultation Timing Association (IOTA) can use your observations to refine the Moon’s profile, but it’s also just plain cool to watch.

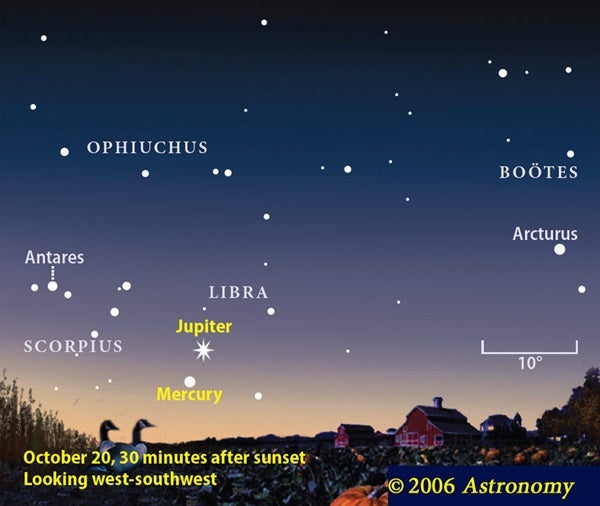

All summer long, Jupiter graced the southern sky as a luminous beacon. Earth’s faster orbital motion around the Sun now is leaving the king of the planets behind to get swallowed by the evening twilight glow. Because Jupiter appears so low in the sky, its image suffers greatly from turbulence in our atmosphere. We’ll be lucky to see more than the two main cloud belts through a telescope.

Mercury climbs away from the Sun in early October and meets Jupiter around the 20th. Unfortunately, this is Mercury’s worst apparition of the year for northern observers. Binoculars will be a must for most skywatchers. From south of the equator, this will be a beautiful event. Be patient, northerners, you’ll get a turn in December.

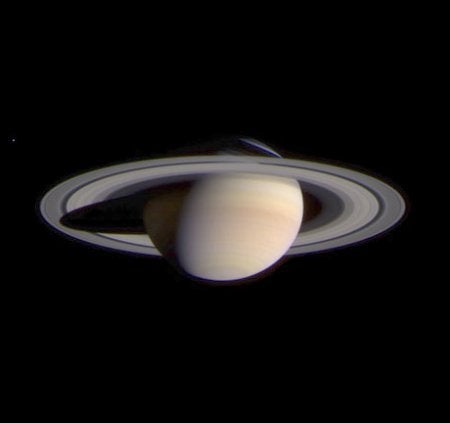

If you’re hungry for planets, think breakfast, and greet Saturn at dawn. It rises around 2 A.M. local daylight time, but conditions will be best when it lies highest in the sky. On the morning of the 16th, a waning crescent Moon joins the ringed planet and the blue-white star Regulus. Saturn’s rings continue to flatten as the planet heads for its equinox in 2009, when the rings will appear edge-on.

Streaking swiftly across the sky, motes of dust burn up as meteors. Although Earth constantly sweeps up interplanetary dust, our planet runs through a slightly denser trail left by Comet 1P/Halley this month. Named after the constellation from which the meteors appear to radiate, the Orionids peak October 21, timed perfectly with New Moon. Organize a group of skygazers to meet out of town, and bring lawn chairs, sleeping bags, and hot drinks to stay warm. Plan to wear winter gear — many observers are surprised at the chill of the late-night air.

About 90 minutes before sunrise, look to the east. If the sky is dark and transparent, you will see a soft glow starting near Saturn and spreading gradually toward the horizon. Sometimes called the false dawn, this is the zodiacal light: sunlight scattering off microscopic dust in the solar system’s plane.

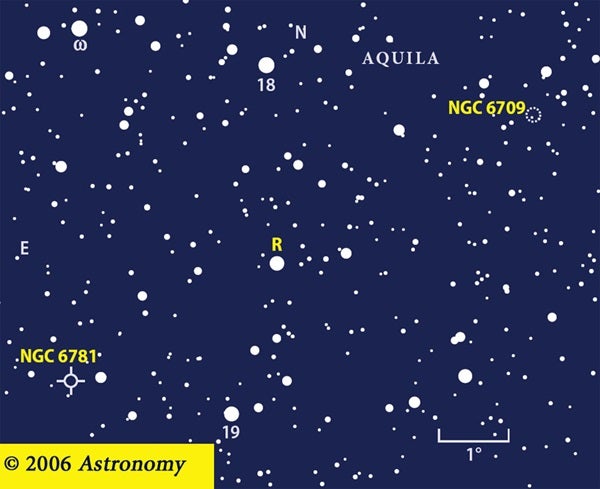

Aquila, a beautiful constellation spread-eagled across the backbone of our home galaxy, lies due south as the sky darkens. The white luminary Altair anchors the southern end of the Summer Triangle, with Deneb in Cygnus and Vega in Lyra shining higher up. Early Arabic culture shared the Greek view of Aquila as an eagle; Altair is an Arabic derivation of this mighty bird’s name.

From a suburban backyard, you can follow the fall of a variable star with binoculars. R Aquilae should reach its maximum brightness of magnitude 6.1 during the first half of October. To prevent confusion with other star catalogs, astronomers designated the first variable star discovered in each constellation R. Subsequent ones run through letters to the alphabet’s end, then double-letter designations take over.

Astronomers don’t know exactly when R Aql will be brightest or how bright it will get, and your observations can help pin it down. Hop over to aavso.org on the web, and download a free comparison chart for R Aql by typing in that name at the upper left. To estimate R’s magnitude, find a nearby star equal to it, or one brighter and another fainter. See how you fare compared with other observers.

Despite Aquila’s decent size and position along the spine of the galaxy, it contains no Messier objects. Don’t let that stop your deep-sky observing, however. Remember, Messier had a 3-inch scope of less-than-stellar quality — you may well have something better.

A delightful star cluster on Aquila’s western side is NGC 6709. It sparkles across 15′ of sky (half the Moon’s apparent diameter), with a total magnitude of 6.7. Dozens of stars, the brightest of which shines at magnitude 9.0, contribute to the glow visible through binoculars. A fanciful Greek letter lambda (λ) springs to mind thanks to the cluster’s curving star chains.

When a star like the Sun enters into old age, it gently puffs off its outer envelope of gas. This allows the white-hot central ember to fluoresce the outflow into visibility. Aquila is home to dozens of these so-called planetary nebulae, which often resemble ghostly versions of Jupiter or Uranus.

NGC 6781 appears roughly circular, almost 2′ across, and glows at magnitude 11.4. If you own a nebula filter, or a light-pollution filter, NGC 6781 will appear to jump out from the background. Such an observation is easy with a small scope from a dark sky. Give it a try from your backyard, too — you may be surprised at what you can see with the help of this technological marvel.

Mercury and Jupiter appear briefly in the twilight sky after sunset this month. The challenge will be in spotting the fainter one, Mercury, as it hugs the southwestern horizon. Fortunately, brilliant Jupiter will guide you. Both Uranus and Neptune are on hand to give binocular viewers a modest challenge on these cool fall evenings. Early morning brings Saturn into view — standing high in the east before dawn.

Try looking for Mercury October 18, when it lies 4° directly below Jupiter. Flanking the two planets are Antares, standing low in the southwest, and Arcturus, somewhat higher than Antares above the western horizon. The planetary pair lies closer to the horizon than either star. Thirty minutes after sunset, Mercury stands a mere 3° high in the southwest, and Jupiter is double that altitude. You’ll need transparent skies and a flat, unobstructed horizon to glimpse Mercury.

Jupiter proves much easier to spot because it’s significantly brighter, shining at magnitude –1.7. Mercury appears 4 times fainter, at magnitude –0.1.

The inner planet shines a bit brighter earlier in the month. On October 12, for example, it glows at magnitude –0.2 and stands 8° to Jupiter’s lower right. From the Southern Hemisphere, where the ecliptic now makes a steep angle to the evening twilight horizon, Mercury and Jupiter stand high in the west after sunset.

Although Jupiter usually shows lots of detail through a telescope, don’t expect much this month. Turbulence in Earth’s atmosphere typically ruins the view of low-altitude objects. A waxing crescent Moon joins Mercury and Jupiter the evening of October 24. The Moon then lies 8° to Mercury’s left (and 8° to Antares’ lower right) and sets an hour after sunset.

Grab a pencil and notepad, and mark the positions of all the objects visible through binoculars between 4.3-magnitude Iota Cap and 5.3-magnitude 29 Cap — then jot down the time and date. Repeat this process over a couple of nights, and you’ll easily notice Neptune’s motion. A digital camera with a zoom lens can perform the same feat: Make a 5-second exposure each night with the camera’s ISO speed setting at its highest value.

Telescopes show little of Neptune beyond its tiny blue-gray disk. Even though it’s 4 times Earth’s diameter, Neptune lies 2.75 billion miles away and so appears only 2.3″ across.

Next find Lambda (λ) Aquarii, a 3.7-magnitude star located midway between Markab, the lower-right star in the Great Square of Pegasus, and Fomalhaut, the brightest star in Piscis Austrinus. Lambda has a neighbor this month: Uranus.

The seventh planet lies within a single Moon-width of Lambda the first half of the month. Glowing at magnitude 5.8, Uranus shows up easily in binoculars and even can be glimpsed without optical aid from a dark-sky site. Uranus passes due south of Lambda October 8/9 and continues to wander westward the rest of the month. The bright star’s proximity makes tracking Uranus’ motion a cinch.

As with Neptune, a telescopic view of Uranus offers distinct color in a small package. Uranus’ disk measures 3.6″ across and shows up readily in the smallest scope. The planet’s blue-green hue makes a nice contrast with Lambda Aquarii’s reddish glow.

Saturn shines at magnitude 0.6, exactly twice as bright as Regulus. The planet looks great through any telescope — all you have to do is bring it to a sharp focus. Saturn’s disk spans 17″ in mid-October, while the rings stretch 39″ across. You should have no trouble seeing the dark Cassini Division, which separates the outer A ring from the brighter B ring.

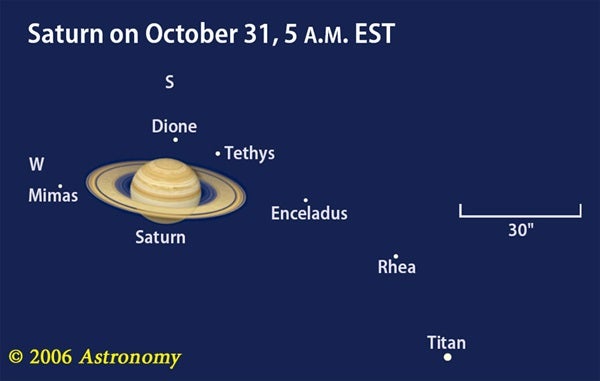

Dozens of moons orbit Saturn, and an impressive handful come to light in small scopes. Titan is bigger and brighter than the others, so it shows up easiest. This 8th-magnitude moon takes 16 days to orbit Saturn. You can find it due north of the planet the morning of October 16 and due south the mornings of October 8 and 24.

Sometimes, the moons align in curious ways. For example, on October 31, Titan lies 1.5′ northeast of Saturn while four fainter moons line up in a trail ending near the planet’s south pole. See if you can spot Rhea, Enceladus, Tethys, and Dione. They glow at magnitudes 9.7, 11.8, 10.4, and 10.5, respectively.

Iapetus lies much farther from Saturn than the other bright moons. It also varies in brightness because it has a dual personality — its leading face is dark, and its trailing face is bright. This means the moon appears reasonably bright (magnitude 10.1) when it lies farthest west of Saturn; at greatest eastern elongation, however, the moon glows 5 times fainter, at magnitude 11.9.

October begins with Iapetus far east of the planet and near its dimmest. Its orbital path carries it across Saturn’s rings and disk the morning of October 19, but Saturn’s brilliant disk will hide it from view except through large telescopes. The following morning, Iapetus lies west of the rings as it heads toward greatest western elongation in early November.

Two planets pass on the far side of the Sun from our earthly vantage point this month. Mars reaches solar conjunction October 22/23. It will be a couple of months before it climbs high enough in the morning sky for us to see it. Venus reaches superior conjunction October 27. Because it lies inside Earth’s orbit, and thus revolves around the Sun faster than our planet, Venus will reappear in the evening sky. It should become visible before year’s end.

Finally, don’t forget to set your clocks back 1 hour October 29, as most of the United States and Canada return to Standard Time.

With dark skies brought to us by a New Moon, prospects look excellent for this year’s annual Orionid meteor shower. The Orionids appear to radiate from a spot near the “Club” asterism in northeastern Orion the Hunter, where that constellation borders Gemini the Twins. The radiant rises before midnight and stands high in the south by 4 A.M., a full 2 hours before dawn. The shower remains active all month, beginning October 2 and ending November 7.

Meteor rates start and end with a trickle, but achieve a substantial peak October 21. (The 1993 and 1998 Orionid showers showed enhanced rates 3 to 4 days earlier, so it’s worth watching the shower over a week’s time centered on the maximum.) Rates can reach 20 meteors per hour, and occasionally more. The predawn hours offer the best viewing.

These meteors are among the fastest of all shower meteors, striking Earth’s upper atmosphere at 41 miles per second. Many leave persistent trains — glowing tubes of ionized gas created by the dust particles burning up.

Orionid meteors derive from debris left behind by Comet 1P/Halley during its innumerable passages through the inner solar system. Earth’s orbit intersects this debris trail in two places, resulting in this fine autumn shower and another good one in May called the Eta Aquarids.

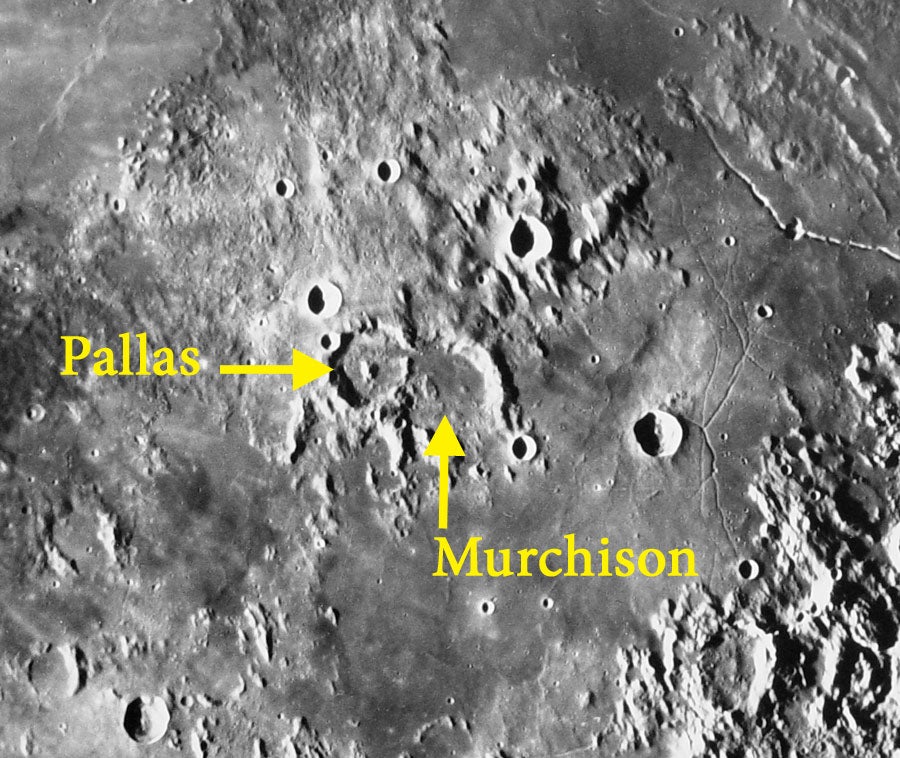

A pair of overlapping and eroded craters lies almost at the center of the Moon’s disk. Pallas and Murchison reside in an upland region between Mare Vaporum and Sinus Medii. With the craters’ central location, sunrise occurs at First Quarter phase and sunset at Last Quarter.

Heavily eroded Murchison spans 36 miles. Its southeastern wall has been obliterated, and a fresh crater, Chladni, stands near this opening into Sinus Medii. Lava flowed into Murchison through this opening, flooding the crater’s floor. To Murchison’s northwest, what remains of the crater’s rim is shared with Pallas, a somewhat-fresher-looking, 31-mile-wide crater with a prominent central peak. Pallas’ northwestern wall has an impact crater, designated Pallas A, that disturbs its line. A larger fresh crater, named Bode, lies just northwest of Pallas.

The two craters are bathed in sunlight at the beginning of October (the Sun rises over the region September 30). The Sun sets there October 13 and rises again October 29.

The sparkling Pleiades star cluster (M45) is always a favorite of beginning deep-sky observers. This month, the cluster also serves as a handy guide to novice asteroid-hunters. The main-belt asteroid 7 Iris lies less than 1 binocular field northwest of M45. Glowing between 7th and 8th magnitude, Iris stands out from the background stars. Although too faint for binoculars to pull in under city lights, it’s well within their reach from a dark sky during the second half of October, when the Moon’s out of the way.

Wait until mid-evening, then use the chart at right to hop over to its rough position with your binoculars or scope. Apart from the pair of stars just north of the asteroid, Iris will be the brightest object in the field. Make a quick sketch of its position relative to the stellar pair and return a night or two later to see that Iris has shifted position. This is direct evidence of its place in our solar system.

John Russell Hind discovered Iris August 13, 1847, from an observatory in London. The asteroid measures about 130 miles across and has a surface reflectivity almost 4 times that of the Moon.

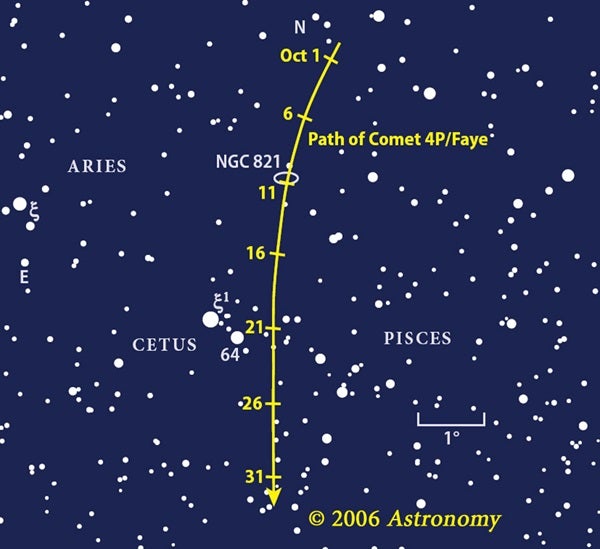

Backyard observers love to observe comets. Bigger and brighter is always better, of course, but there’s just something special about these diffuse balls of light that keeps backyard observers coming back for more. From a scientific standpoint, we know comets formed early in the solar system’s history, and, therefore, contain primordial matter. Perhaps they carried the seeds of life to our little blue planet. But without a doubt, we know they can take life away with a huge impact.

The more romantic side of us connects comets with astronomers across the ages — from Edmond Halley, who discovered that some comets return to our vicinity on long elliptical paths, to Charles Messier, the “comet ferret” who sought to differentiate comets and deep-sky objects. Through our modern telescopes, we see the sky much as they did, making it easy for our thoughts to drift back in time before the age of spacecraft and astrophysics.

Comet 4P/Faye, one of the first comets to earn the “P” designation for being recognized as periodic, rises during the early evening in the east where Aries, Pisces, and Cetus come together. You’ll get a better view if you wait until late evening, once this region climbs to a decent altitude. (The chart at left shows Faye’s position at 4 A.M. EDT.) Our window of opportunity opens around October 10, but conditions improve even more after midmonth. A “Messier moment” presents itself the night of October 10/11, when Faye passes close to the background galaxy NGC 821.

The dirty snowball should glow around 9th magnitude, a moderately easy target for a 4-inch scope out in the country. Fainter and smaller than the comet, NGC 821 glows at magnitude 10.7. Although the two will look similar, notice the differences in their structures and brightness profiles.