The Research Brief is a short take about interesting academic work.

The big idea

A bright flash of gamma rays from the constellation Boötes that lasted nearly one minute came from a kilonova, as we described in a new paper. This finding challenges what astronomers know about some of the most powerful events in the universe.

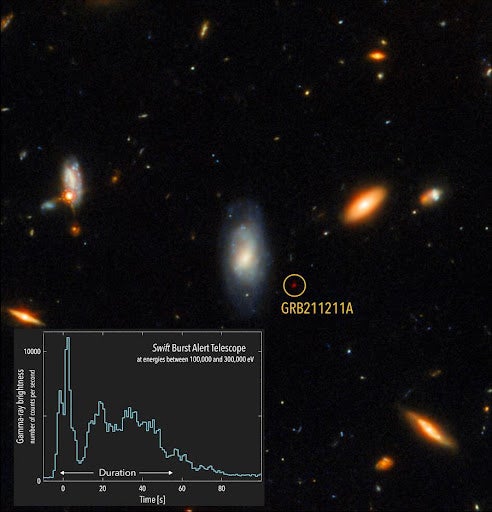

The unusual cosmic explosion was detected by the Neil Gehrels Swift observatory on Dec. 11, 2021, as the satellite orbited Earth. When astronomers pointed other telescopes at the part of the sky where this large blast of gamma rays – named GRB211211A – came from, they saw a glow of visible and infrared light known as a kilonova. The particular wavelengths of light coming from this explosion allowed our team to identify the source of the unusual gamma-ray burst as two neutron stars colliding and merging together.

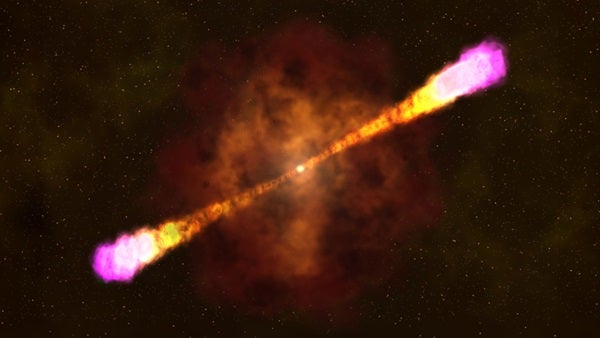

Gamma rays are the most energetic form of electromagnetic radiation. In just a few seconds, a gamma-ray burst blasts out the same amount of energy that the Sun will radiate throughout its entire life. Gamma-ray bursts are the most powerful events in the universe, and astronomers think only two cosmic scenarios can produce gamma-ray bursts.

The most common sources are the deaths of stars 30 to 50 times more massive than the Sun. The catastrophic destruction of one these large stars is called a supernova. When they explode, the stars create black holes that consume the leftover debris. These black holes emit a jet of matter and electromagnetic radiation that moves at close to the speed of light. In moments after the black hole starts emitting this high-energy stream of matter and radiation, the jet produces a burst of gamma rays that can last for minutes.

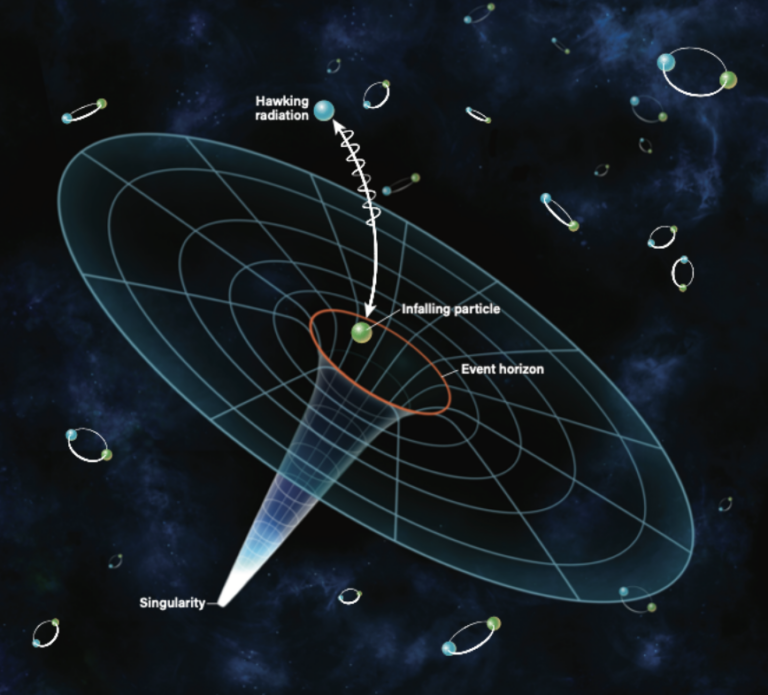

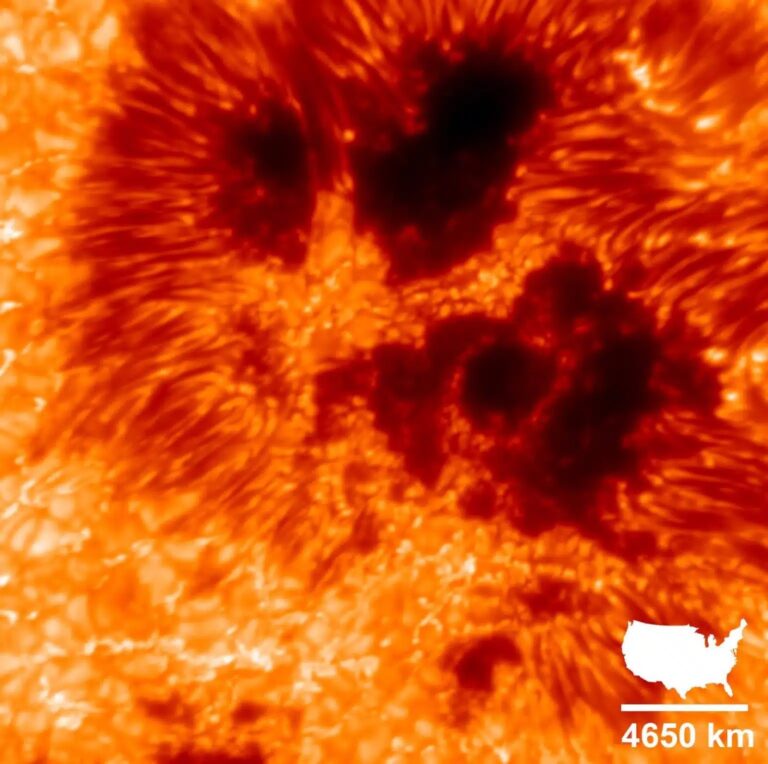

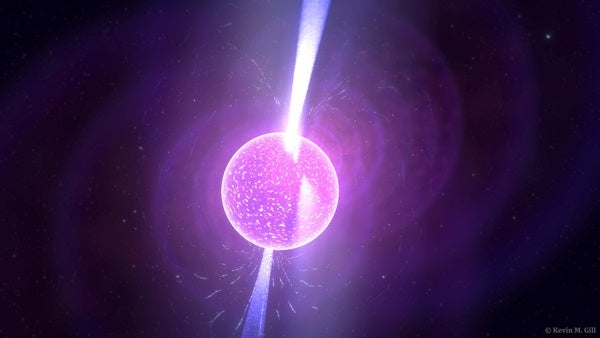

Kilonovae are the second type of events associated with gamma-ray bursts. Kilonovae occur when a neutron star merges with another neutron star or is consumed by a black hole. Neutron stars are rather small stars – about 1.4 to 2 times the mass of the Sun, though only dozens of miles across.

When two of these tiny, dense stars merge to produce a black hole, they leave very little material behind. Compared with the long-lasting feast a black hole gets after a supernova, kilonovae leave a black hole with little more than a snack that results in a gamma-ray burst that lasts only a second or two at most.

For over 20 years, astronomers thought that kilonovae accompanied short gamma-ray bursts and supernovae accompanied long ones. So when our team started looking at the wealth of data and images collected on the minute-long burst in December 2021, we expected to see a supernova. Much to our surprise, we found a kilonova.

Why it matters

Kilonovae are cosmic factories that create heavy metals, including gold, platinum, iodine and uranium. Because they enrich the chemical composition of the universe, kilonovae are critical to providing the basic ingredients for the formation of planets and life.

GRB211211A’s long duration contradicts existing theories of how gamma-ray bursts relate to supernovae and kilonovae. This finding shows that there is still a lot astronomers like us don’t understand about these powerful and important processes and suggests that there may be other ways the universe can produce heavy metals.

Kilonovae are responsible for producing heavy metals – like gold, uranium and iodine – that are important for many processes in the universe.

What still isn’t known

The initial images and data gathered on this interesting event look like a kilonova produced from the collision of two neutron stars. But the long-lasting burst of gamma rays throws doubt on what exactly happened. It is possible that one of the players was a rare neutron star with an incredibly powerful magnetic field – called a magnetar. The burst could also have been the result of a neutron star being torn apart by its companion black hole. Or astronomers could have just witnessed a new, previously unknown type of stellar crash.

What’s next

The few exotic stellar encounters that produce gamma-ray bursts can look very similar to one another across the electromagnetic spectrum. However, the unique gravitational wave signatures they produce could be the key to solving the enigma. The gravitational wave detectors LIGO, Virgo and KAGRA did not see GRB211211A, as they were all offline for improvements. If they can catch a long-duration gamma-ray burst after they begin operating again in 2023, the combination of gravitational wave and electromagnetic data may solve the mystery of this newly discovered event.

![]()

Eleonora Troja, Associate Professor of Astrophysics, University of Rome Tor Vergata and Simone Dichiara, Assistant Research Professor of Astrophysics, Penn State

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.