The would-be rescuers opened the hatch to find a scene of indescribable horror. All three cosmonauts lay dead in their seats, with blue splotches on their faces and blood trickling from their noses and ears. On June 30, 1971, humankind was forced to grapple with the first — and so far only — deaths to occur in space.

A troubled mission

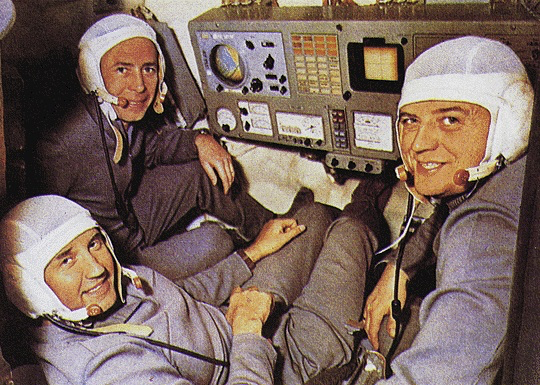

From the outset, Soyuz 11 was an unhappy assignment. After Neil Armstrong’s historic first steps on the Moon, the Soviets nixed their own lunar landing plans in favor of an Earth-orbiting space station. Salyut 1 was launched in April 1971, but it first crew failed to dock with the station during the Soyuz 10 mission. That meant it was up to Alexei Leonov (the world’s first spacewalker), Valeri Kubasov, and Pyotr Kolodin to try again with Soyuz 11.

But three days before launch, during a routine exam, doctors found a swelling on Kubasov’s right lung. Fearing tuberculosis, the whole crew was replaced by their backups. Kubasov’s inflammation turned out to be due to a pollen allergy, but top brass unflinchingly stood by their decision. The cosmonauts were mad; Kolodin returned to his room and got drunk, crying in rage and frustration. Yet, it must have been no easier for the backup crew, who were now faced with accomplishing the longest space mission ever attempted.

In his memoir Two Sides of the Moon, Leonov recalled the palpable sense of dread the astronauts felt. A keen artist, he did a pencil sketch of Patsayev the night before his launch, dubbing it “Patsayev’s Eyes.” It was obvious that the quiet mechanical engineer — a Renaissance man of the cosmonaut corps who loved literature and music, and whose father died defending Moscow from Nazi Germany — was visibly troubled.

The replacement commander of Soyuz 11 was Dobrovolski, a fighter pilot and accomplished parachutist. As a boy, his fingers were smashed by Nazi thugs as punishment for providing ammunition and messages to resistance fighters. Years later, during cosmonaut training in the isolation chamber, this devoted family man whiled away the hours by carving a tiny wooden doll for his daughter.

Meanwhile, the energetic Volkov was the only one of the replacement crew who had flown before. A talented athlete and boxer, the wiry aeronautical engineer would also become the first accredited journalist in space. And during Soyuz 11, his rugged good looks made him somewhat of a pinup icon for Russian women.

Manning a new space station

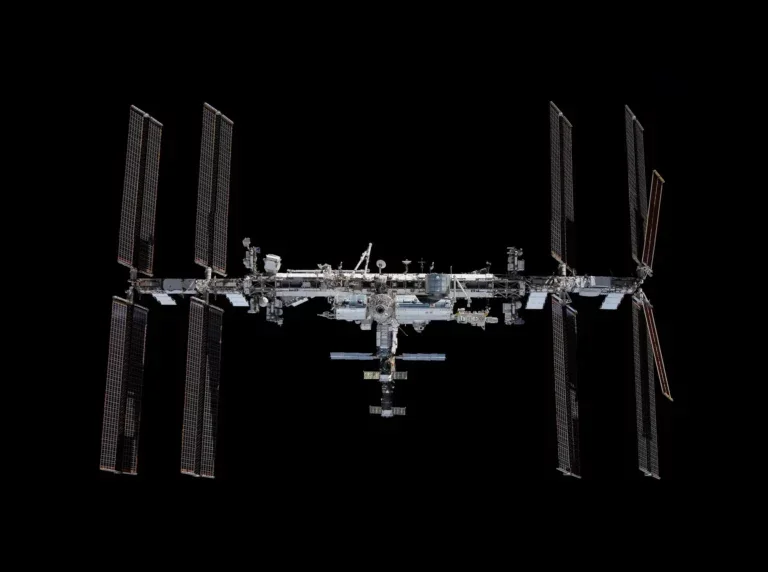

After launching on June 6, 1971, Soyuz 11’s daylong trip to Salyut 1 proved quite uneventful, with the three cosmonauts boarding the new space station with few issues. For the next three weeks, they carried out many experiments, including nurturing Chinese cabbage and bulb onions, taking spectrograms of stars, and photographing snow and ice on the banks of the River Volga. The orbiting trio were even featured on Soviet evening television.

Still, happiness proved elusive. The disjointed shift work became a grueling marathon, the monotony of which Dobrovolski lamented in his ever-present diary. An overheating instrument also flooded part of the station with smoke, taxing the cosmonauts’ nerves and testing their ability to remain a cohesive crew. Fortunately, some harmony returned when Patsayev became the first man to celebrate a birthday in space, with his crewmates treating him to a surprise special meal of veal, cookies, and blackberry juice.

Unfortunately, it would be Patsayev’s last birthday.

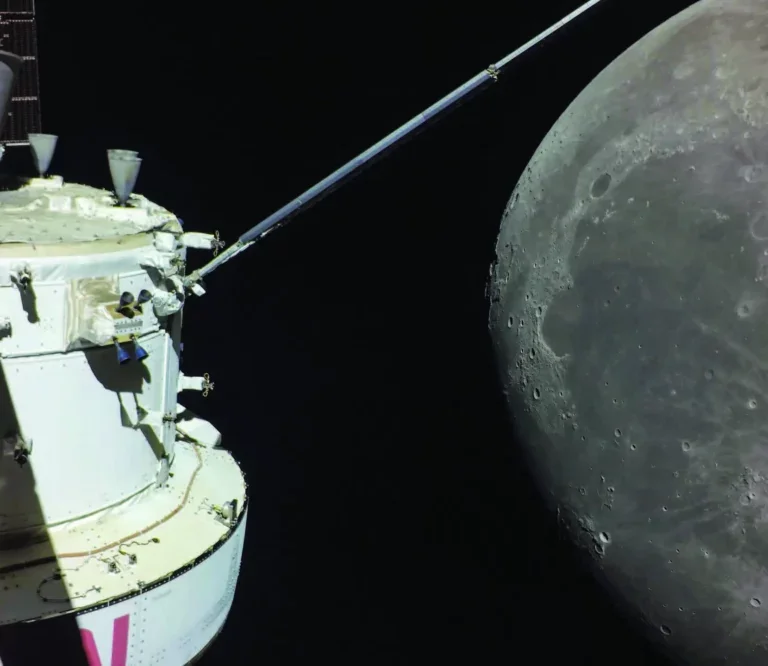

Late on June 29, Soyuz 11 finally undocked from Salyut 1. Three hours later, with their primary mission complete, the cosmonauts fired their ship’s engine to return to Earth. Volkov jokingly asked flight controllers to ensure that a supply of cognac — a traditional welcome-home gift — was waiting for them at their landing site.

Twenty-nine minutes before touchdown, while still at an altitude of around 100 miles (160 kilometres), explosive charges fired, as planned, to separate Soyuz 11’s orbital and instrument modules. The bell-shaped capsule was now the crew’s only defense against the fiery furnace of re-entry.

A gruesome discovery

What happened next happened fast.

As soon as the other modules were jettisoned, the pressure inside the crew capsule precipitously fell. All the air was escaping from Soyuz 11. Based on the positions of the astronauts’ bodies upon their discovery, investigators concluded that Dobrovolski and Volkov had unstrapped from their seats to attempt to find the source of the leak. Health trackers showed their heart rates soared as they searched. But time was not on their side. Within 50 seconds, Patsayev’s pulse dropped to levels consistent with oxygen starvation. And within 110 seconds, all three cosmonauts were dead.

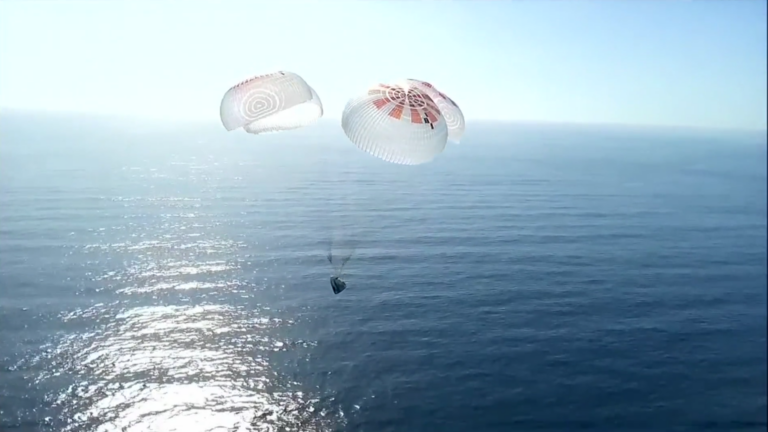

At this point, Mission Control was unaware of the gravity of the situation. As attempts to contact the crew over VHF radio were met with stony silence, however, a pervasive sense of unease crept into the room. Twenty-two minutes before touchdown, military radar detected the rapidly descending capsule entering Soviet airspace. Because the craft was still re-entering the atmosphere, and therefore sheathed in super-heated plasma, communications remained impossible.

Still, there was no word from the crew.

Mission Control temporarily experienced elation when the helicopter commander reported that the capsule had landed and the recovery team was setting down nearby. In their minds, they were mere minutes from opening the hatch and treating the cosmonauts to the sweet smells of home for the first time in three weeks. Within two minutes of touchdown, search and rescue personnel reached Soyuz 11. They made their presence known by hammering their greetings on the ship’s hull.

There was no reply from within.

When they opened the hatch, they discovered all three cosmonauts slumped over motionless. Their faces were covered with dark, bruise-like spots, and blood was seeping from their noses and ears. Dobrovolski was still warm, but all attempts at resuscitation proved fruitless.

The first contact between the rescuers and Mission Control, when it came, took the form of three numbers: 1-1-1. It was a code to denote each of the cosmonauts’ health. The number 5 stood for excellent condition, 4 indicated good condition, 3 meant injuries were suffered, 2 emphasized those injuries were serious, and 1 meant they were fatal. A string of ones instantly told flight controllers that Dobrovolski, Volkov, and Patsayev were all dead.

Investigators later determined that the cause of these first space fatalities was a faulty valve that sprang open during the separation of the orbital and instrument modules. With no way to fix the leak, the cosmonauts didn’t stand a chance. The tragedy prompted national grief across the Soviet Union. Even stone-faced Premier Leonid Brezhnev wiped away tears when he eventually filed past the men’s coffins.

As a direct result of the accident, future Soyuz ships came equipped with sturdier valves featuring quick-action chokes that can quickly plug any air leaks. But most significantly, all future crews also don pressure suits throughout both launch and landing.

Thankfully, since that tragic day 50 years ago, every Soyuz crew has safely launched and landed.