Computers and outer space have been inextricably linked since Sputnik launched the space age in 1957. But it wasn’t until the 1960s that computers were advanced enough to facilitate humanity’s most daring space adventure of landing on the Moon. The sweeping advances that made those missions possible ultimately shaped the way we use computers to stay connected around the world today.

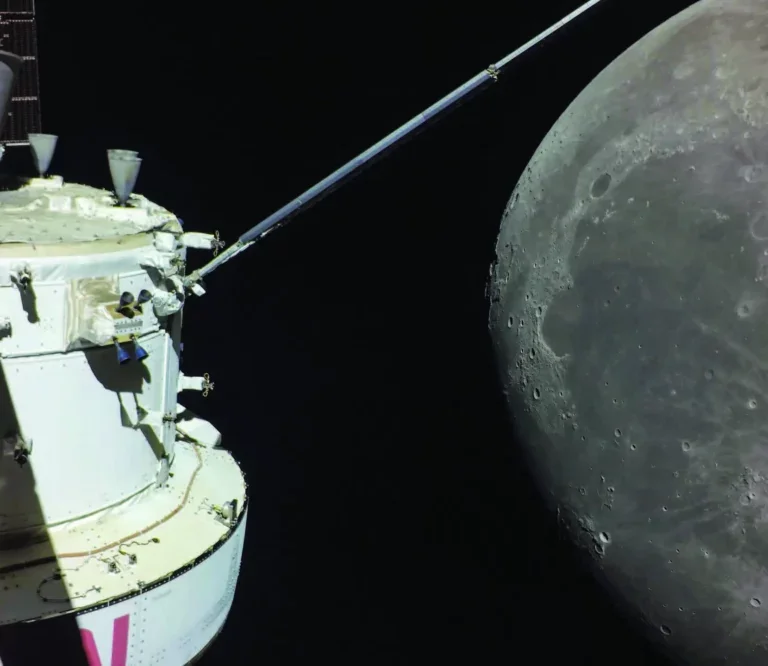

Early on in the Apollo program’s development, NASA was already considering the computational might it would need to land men on the Moon. The space agency knew that it would need more than just computing power on the spacecraft, it would need a sophisticated and powerful network to deal with all the data of a lunar mission, one that could receive, manage, work with, and transfer all the information sent to the spacecraft as well as what was beamed back to Earth. With two spacecraft flying together a quarter-million miles away, there was going to be a lot of data.

To solve this problem, NASA turned to the International Business Machines Corporation, better known as IBM. At the time, IBM’s 7090 series of mainframe computers formed the backbone of NASA’s mission control and data management for the Mercury and Gemini programs. As luck would have it, in 1964 when NASA was starting to figure out its Apollo needs, IBM unveiled its newest series of computers, called System 360 (S/360). The design incorporated IBM’s lessons learned from its early work with the space agency.

Almost as though anticipating NASA’s needs, these computers weren’t just singular systems, they could be networked together to build a multiprocessing system. The new computer’s operating system called OS/360 boasted a new ability to multitask. By the fall of 1966, NASA had twin 360s at the Goddard Spaceflight Center forming the basis of its new computing hub for Apollo missions.

But for all their capabilities, memory on these new computers was a problem. Each 360 had one million bytes of main memory. That’s about four times more than the Gemini-era computers but nothing by modern standards; desktop computers now can have more than a terabyte of memory or about six orders of magnitude more than one 360. Because the missions were expected to generate more data than the computers could handle, engineers developed shorthand code to shave off a few words here and there, trying to eke out as much memory space as they could, a risky practice that threatened to introduce errors into the system. The data, then, was in a sort of engineering shorthand rather than full sentences.

Consider a Saturn V launch, for example. The astronauts, all of whom were also aircraft pilots in the Apollo era, wanted to be in control of the mission from start to finish, including the launch. But NASA knew that things happen so fast in a launch that human reaction time can’t keep up so gave the Saturn V its own brain called the “instrument unit.” The instrument unit could sense altitude, acceleration, velocity, and position with such precision that it ultimately controlled when the stages fired during launch, when spent hardware was jettisoned, and managed the rocket’s guidance.

All that data — done in space-saving shorthand but still equating to roughly a novel a minute in terms of bytes — was then sent to the IBM System/360 computers on the ground so NASA engineers and technicians could monitor the rocket’s trajectory. The computers absorbed, translated, calculated, evaluated and relayed this information for display.

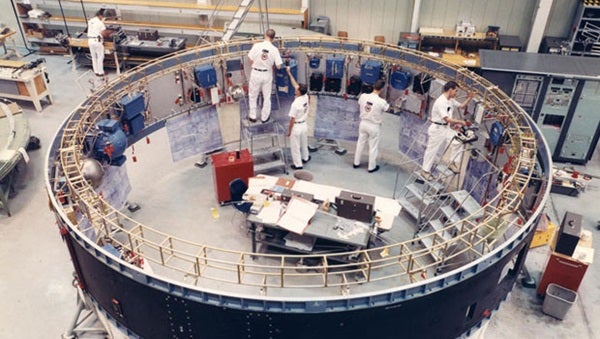

IBM employees from across the nation built the computers and wrote many of the software programs that launched the Apollo missions to the Moon and guided them back to Earth. IBM engineers also developed the mini integrated circuits that meant computers could be small enough to fit inside a rocket or spacecraft. The instrument unit was built at the Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama before it was shipped to the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, for final testing and integration into the rocket. But their work wasn’t done. Throughout the Apollo flights, IBM technicians sat alongside mission controllers at the Johnson Space Center in Houston, reading data and making minute-by-minute analyses. A host of IBM engineers were also on hand at the Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, the home of the worldwide network of relay and tracking stations.

The System/360 legacy didn’t end with the end of the Apollo program. Its true legacy is the beginning of computer compatibility. For the first time, on the Apollo program, machines across a product line were able to talk to and work with each other. With System/360, it wasn’t about automating a task, it was about managing complex processes through whole systems of computers.

The System/360 was more than a computer, it was a compatible family of machines that pioneered the eight-bit byte — eight values of “off” or “on” (1 or 0) per byte — and supported different processing speeds at once, effectively revolutionizing the way we think about what computers can do.