Key Takeaways:

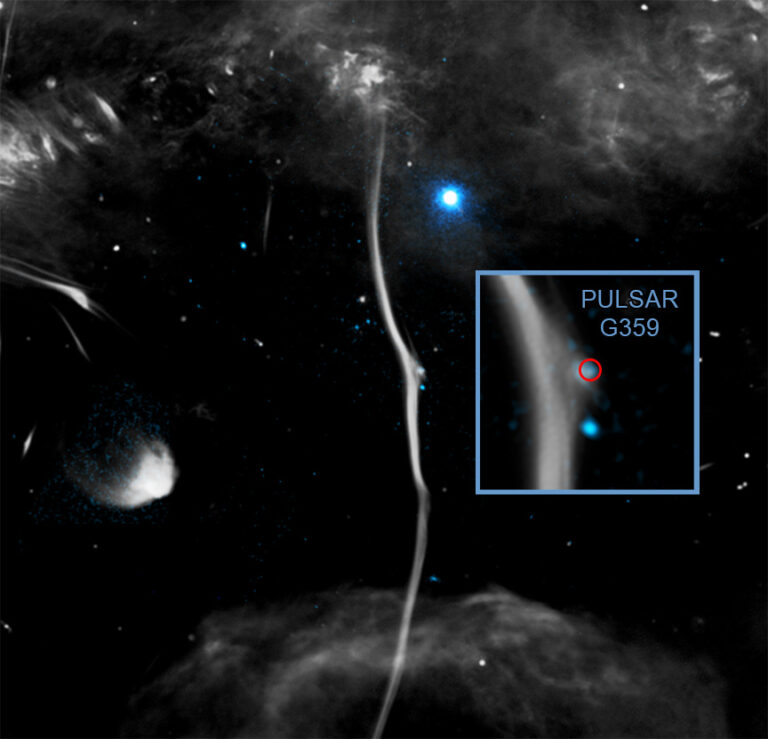

The ripples in space-time traveled some 500 million light-years and reached the detectors at LIGO, as well as its Italian sister observatory, Virgo, at around 4 a.m. E.T. Thursday, April 25. Team members say there’s a more than 99 percent chance that the gravitational waves were created from a binary neutron star merger.

Shot at a Kilonova

In the moments after the event, a notice went out alerting astronomers around the world to turn their telescopes to the heavens in hopes of catching light from the explosion, called a kilonova. Kilonovae are 1,000 times brighter than normal novae, and they create huge amounts of heavy elements, like gold and platinum. That brightness makes it easy for astronomers to find these events in the night sky — provided they’ve been given a heads-up and location from LIGO first.

LIGO’s twin L-shaped observatories — one in Washington state and one in Louisiana — work by shooting a laser beam down the long legs of their “L.” Their experimental setup is precise enough that even the minimal disturbance caused by a passing gravitational wave is enough to trigger a slight change in the laser’s appearance. It made the first ever detection of gravitational waves in 2016. Then it followed up by detecting merging neutron stars in 2017.

Scientists use any slight delays between when signals reach the detectors to help them better triangulate where the waves originated in the sky. But one of LIGO’s twin detectors was offline Thursday when the gravitational wave reached Earth, making it hard for astronomers to triangulate exactly where the signal was coming from. That sent astronomers racing to image as many galaxies as they could across a region covering one-quarter of the sky.

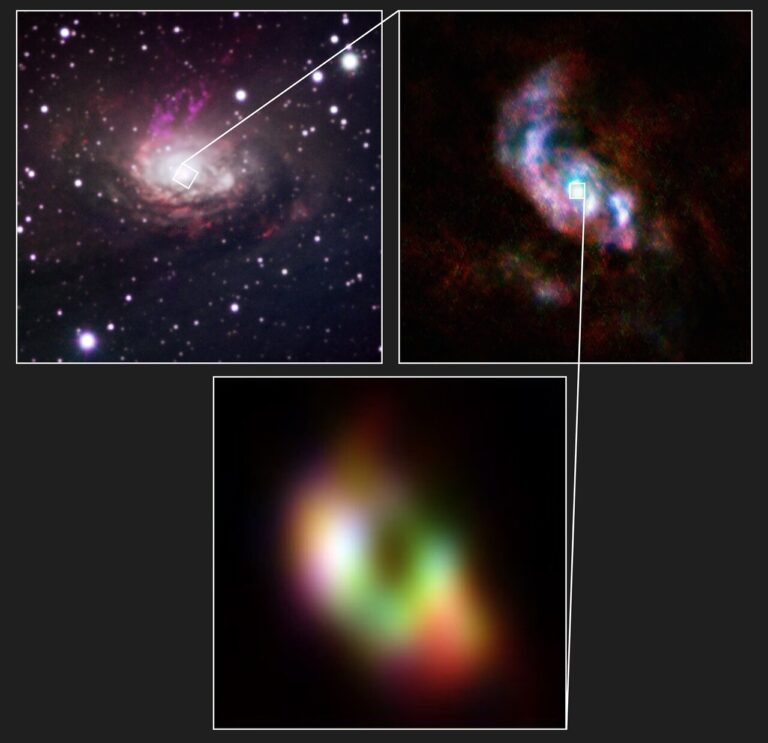

And instead of finding one potential binary neutron star merger, astronomers turned up at least two different candidates. Now the question is which, if any, are related to the gravitational wave that LIGO saw. Sorting that out will require more observations, which were already happening around the world as darkness fell.

“I would assume that every observatory in the world is observing this now,” says astronomer Josh Simon of the Carnegie Observatories. “These two candidates (they’ve) found are relatively close to the equator, so they can be seen from both the Northern and Southern Hemisphere.”

Simon also says that, as of Thursday afternoon in the United States, telescopes in Europe and elsewhere should be gathering spectra on these objects. His fellow astronomers at the Carnegie Observatories turned their telescopes at Chile’s Las Campanas Observatory to the event Thursday night.

History-Making Merger

LIGO’s first detection of a neutron star merger came in August 2017, when scientists detected gravitational ripples from a collision that occurred about 130 million light-years away. Astronomers around the world immediately turned their telescopes to the collision’s location in the sky, allowing them to gather a range of observations across the electromagnetic spectrum.

The 2017 detection was the first time an astronomical event had been observed with both light and gravitational waves, ushering in a new era of “multi-messenger astronomy.” The resulting information gave scientists invaluable data on how heavy elements are created, a direct measurement of the expansion of the universe and evidence that gravitational waves travel at the speed of light, among other things.

This second observation appears to have been slightly too far away for astronomers to get some of of the data they had hoped for, such as how nuclear matter behaves during the intense explosions.

“After the first event, it was clear that a lot of the action was going on immediately after the explosion, so we wanted to get observations as soon as possible,” Simon says. In this case, with one of LIGO’s detectors down, they couldn’t find the object as quickly as they did in 2017.

So far, one difference is that, unlike last time, astronomers haven’t spotted any signs of gamma-ray bursts, says University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee physicist Jolien Creighton, a LIGO team member.

But regardless, having additional observations should help us learn more about these extreme cosmic collisions.

“It gives us a much better handle on the rate of such collisions,” says Stefan Ballmer, associate physics professor at Syracuse University and LIGO member. “The upshot: if we just observe a little longer we will get the strong signal we are hoping for.”

LIGO just started its third observing run a few weeks ago. And, in the past, these detections were kept a closely guarded secret until they were confirmed, peer-reviewed and published. But with this latest round, LIGO and Virgo have opened their detections up to the public. In this latest run, LIGO has also already detected three potential black hole collisions, bringing its total lifetime haul to 13.