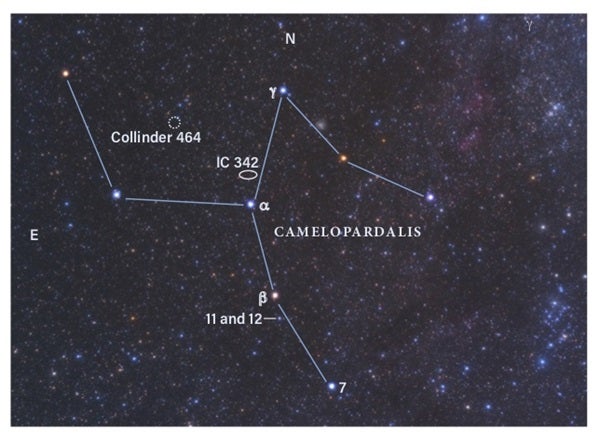

Last month, we visited the constellation Lepus, found south of Orion. This month, we will turn our attention toward the area north of Auriga. This region appears nearly starless even under dark rural skies. Ancient stargazers also thought this section of the sky was empty, so never concocted a constellation there. It wasn’t until 1612 that the Dutch-Flemish astronomer Petrus Plancius drew a pattern among those faint points: A giraffe, which he called Camelopardalis.

That’s right — Camelopardalis is not a camel, despite the misleading name. Translated, the Latin term Camelopardalis roughly means “camel leopard,” which comes from the way ancient Greeks described giraffes. So, even though they didn’t conceive the constellation, in one sense they did give it a name.

While Camelopardalis may not look like much to the unaided eye, it does hold some buried treasure for binocular users. Are you up for a hunt?

The brightest star in the celestial giraffe is 4th-magnitude Beta (β) Camelopardalis, found about 15° north of Capella (Alpha [α] Aurigae). Beta Cam is a type G1 yellow supergiant, slightly hotter than our Sun and over six times as massive. It lies 870 light-years from our solar system, roughly the same distance as Rigel (Beta [β] Orionis). Through binoculars, it displays a subtle yellowish tint.

While you are enjoying Beta Cam, take notice of a fainter pair of stars just a degree to the south. Those are 11 and 12 Camelopardalis. They appear just 3′ apart on the sky. Through binoculars, 5th-magnitude 11 Cam shows a delicate blue-white hue, while 6th-magnitude 12 Cam appears orangish. But their numerical affiliation is purely circumstantial, I’m afraid. Astronomers estimate that 11 Cam is 710 light-years from Earth, while 12 Cam is about 10 light-years closer. Although they are relatively near each other in space, they do not form a binary star system.

Given the sparseness of the area, you would hardly expect to find an open star cluster here. And yet there is: Collinder 464 is a late entry in Per Collinder’s 1931 catalog of 471 open clusters. Several clusters Collinder listed were previously included in the Messier and NGC listings, but others were not, including number 464. To find it for yourself, return to Alpha Cam and continue another 8.5° toward Polaris. Keep your eyes peeled for a dozen faint stars loosely gathered across an area measuring about 1° by 2°. The 5th-magnitude star SAO 5455 lies near the center of the cluster. By using a little imagination and borrowing some non-cluster stars in the immediate area, I see Collinder 464 forming the profile of a small dog. In my mind, the dog is facing west, with its legs stretching to the south and tail standing at attention to the east. The stars that mark the tip of the dog’s nose, ear, and tail look very slightly orangish, while the others appear white. Years ago, I nicknamed the cluster “Amy” after my toy poodle, who loyally accompanied me on many a night viewing the sky.

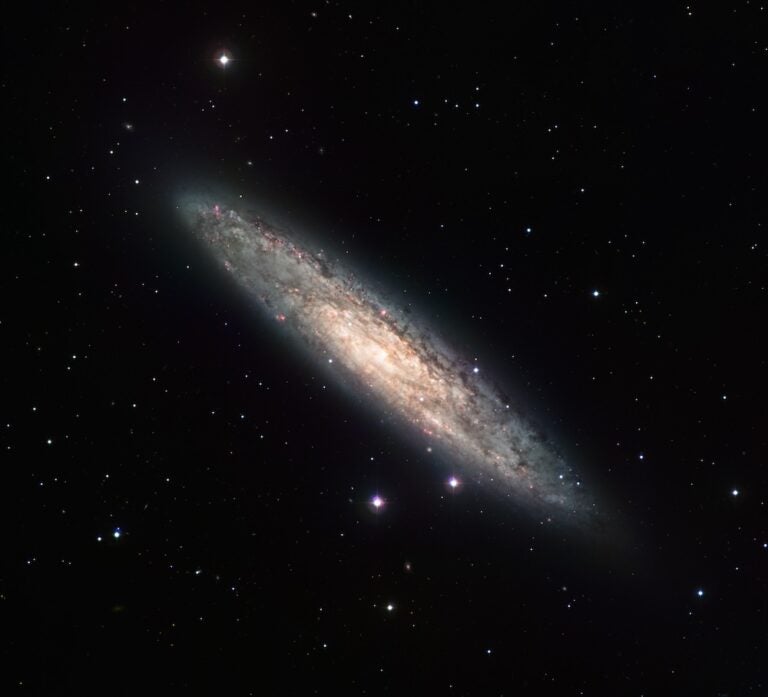

Our final stop this month is spiral galaxy NGC 2403, one of the brightest galaxies north of the celestial equator that Charles Messier missed. Instead, it was discovered by William Herschel in 1788. Although NGC 2403 lies within the borders of Camelopardalis, it is most easily found by looking about 8° northwest of 3rd-magnitude Muscida (Omicron [ο] Ursae Majoris), the star at the tip of the Great Bear’s nose. Look for its soft 9th-magnitude glow just north of a rectangle of 8th-magnitude stars. Through my 10×50 binoculars, NGC 2403 displays a dim oval disk skewed northwest-southeast. It lies approximately 10 million light-years away — about the same distance as M81 and M82, which are 14° to its east. Researchers believe that NGC 2403 is likely an outlying member of that galactic group.

We will explore the western portion of Camelopardalis later this fall. But for now, if you have any questions, comments, or suggested targets, I would enjoy hearing from you. Contact me through my website, philharrington.net. Until next month, remember that two eyes are better than one.