Although renderings of Cetus date back to its first appearance as one of 48 star patterns in the Almagest, written by Ptolemy around A.D. 150, one particular star went unnoticed. That could have been because it’s not always visible. At times, it shines as brightly as the constellation’s brightest star, Diphda (Beta [β] Ceti), while at others, it disappears entirely.

The earliest observation of this strange star’s eccentric behavior was made by German astronomer David Fabricius in 1596, making it the first variable star ever discovered. Although it was designated Omicron (ο) Ceti in Johann Bayer’s 1603 catalog of stars, it wasn’t until 1662 that Polish astronomer Johannes Hevelius christened it Mira, meaning “wonderful.”

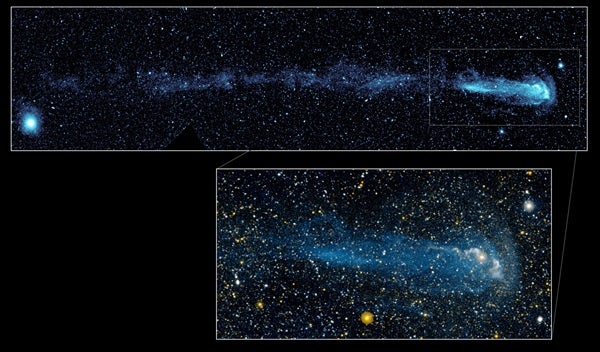

Mira is the archetype of a class of stars known as long-period variables, red giants that steadily pulse over periods lasting about a year. In Mira’s case, the period is 332 days. During that time, it fluctuates from 2nd to 10th magnitude, making it nearly 1,600 times brighter at maximum than at minimum.

Mira’s light curve, a plot of the star’s magnitude over time, shows that it ascends in brightness quickly but trails off toward minimum more slowly. Mira was last at maximum brightness in early December 2019. Throughout last winter and this past spring, it dwindled in brightness as it set earlier each night, eventually disappearing into the sunset. Mira returned to the predawn sky at the start of summer, growing in brightness as it progressively rose earlier each morning. It is anticipated to be back at full light early this month.

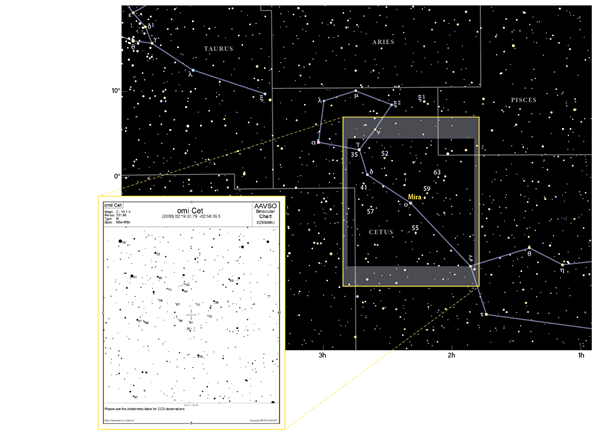

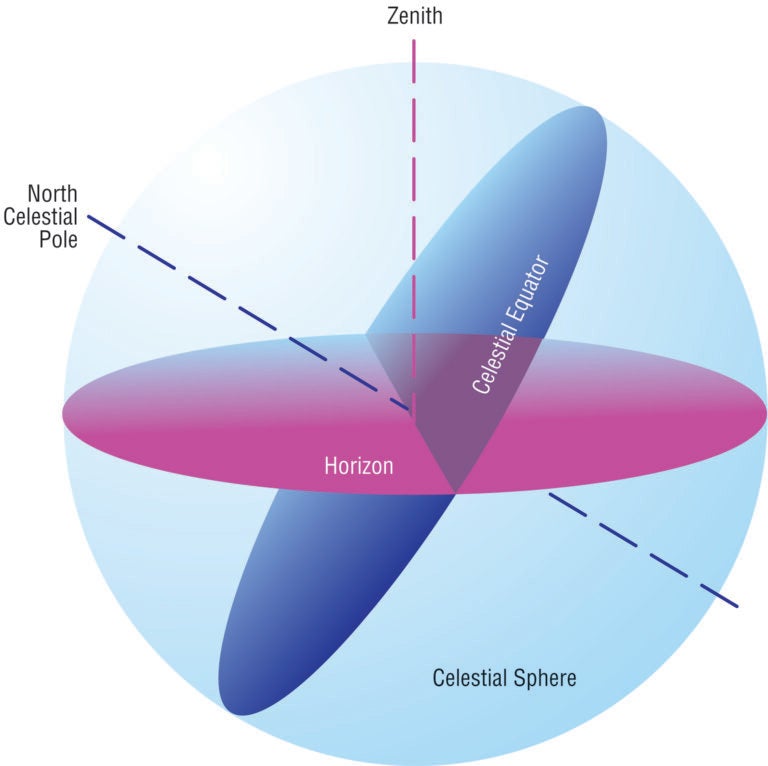

As October opens, Mira rises around 8 P.M. local standard time (9 P.M. Daylight Saving Time). But you should wait at least two hours for it to rise higher above the horizon. To find it, imagine the Hyades, the head of Taurus the Bull, as an arrowhead. Follow its aim southwestward, either by eye or through binoculars, for about 24° to the star Menkar (Alpha [α] Ceti). Menkar is joined by four fainter stars to create a pentagon that was portrayed on classical star maps as Cetus’ hideous head. In fact, the name Menkar stemmed from the Arabic word for “nostril.”

Once you locate the sea monster’s head, slip 12° to the southwest, where you’ll find a reddish star. That’s Mira. (Or maybe you’ll see nothing. It all depends on when you’re reading this.) Look for it a little south of the central point in an equilateral triangle of 5th- and 6th-magnitude stars.

From there, enter “omi Cet” in the form’s top field, which asks for the object’s name. Next, select the chart’s scale from the dropdown menu for predefined scale. “A” is the most appropriate choice for binoculars. Under Advanced Options, pick the chart’s magnitude limit, typically 7, 8, or 9 through 50mm binoculars, depending on light pollution. Farther down, make sure you select “North Up” and “East Left,” and finally choose the “Binocular” special chart. Hit “Plot Chart” and voilà, you have a chart that you can print or save to your device to bring outside.

To gauge Mira’s brightness, evaluate it against the plotted comparison stars. You will immediately notice that many stars have numbers next to them, such as 54, 65, and 81. Those are their magnitude values with the decimal omitted to avoid confusing it for another star.

It’s best to judge the variable star’s brightness by evaluating it against one comparison star that’s a little brighter and a second that’s a little dimmer. For example, let’s say that Mira appears brighter than the 4.1-magnitude (labeled 41) star to its northeast, but fainter than the 3.5-magnitude (35) star farther northeast. If Mira appears to be halfway between the two in brightness, then your guesstimate for its magnitude will be 3.8. If it seems closer to the “35” star, then your estimate might be 3.6 or 3.7; a little fainter, then closer to 3.9 or 4.0.

It’s most difficult to estimate Mira’s brightness accurately when it’s near maximum for want of suitable comparison stars. The field of view of the AAVSO chart is too narrow. Instead, check out the wider-scale chart found on https://freestarcharts.com/magnificent-mira-the-wonderful-reaches-peak-magnitude. This chart expands the view to include the stars of the sea monster’s pentagonal head as well as some in neighboring Pisces. Although drawn for October 2011, it’s still useful nine years later, save for the plotted position of Jupiter.

I hope you enjoy Mira’s wonderful show this fall and winter. Suggestions and comments are always welcome. Contact me through my website, philharrington.net. Until next time, remember that two eyes are better than one.