Key Takeaways:

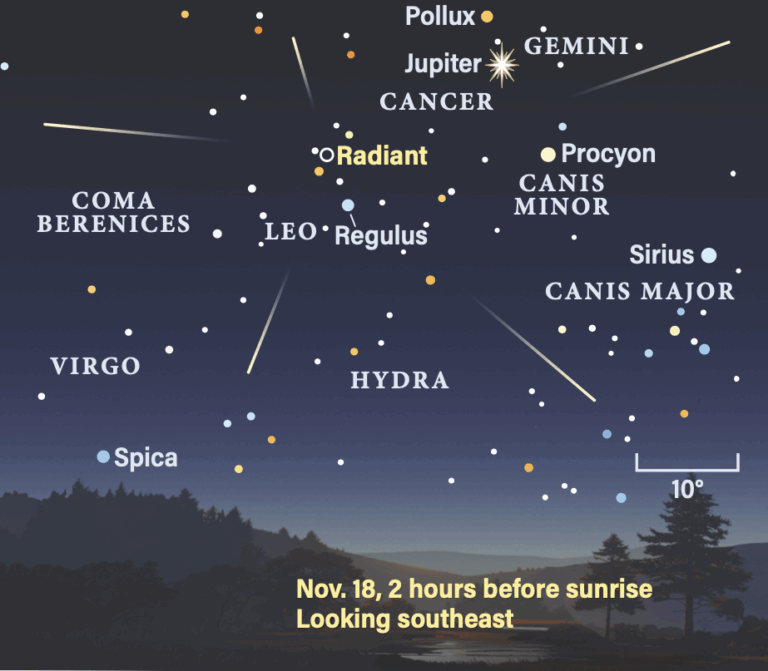

As Orion marches toward the western horizon in pursuit of Taurus, his attending small dog, Canis Minor, lags behind. Canis Minor is one of those constellations that makes me wonder how anyone could imagine seeing the namesake figure among its stars. After all, Canis Minor is drawn from only two: Procyon [Alpha (α) Canis Minoris] and Gomeisa [Beta (β) Canis Minoris]. A small dog from two stars? Maybe a hot dog, but that’s the best I can do.

At third magnitude, Gomeisa appears much less impressive than Procyon. If you are observing from a heavily light-polluted area, you might need binoculars just to see it. But the Small Dog’s Beta star would rank “alpha” if placed side by side with Procyon; its diminutive appearance is due to being 15 times farther away. Gomeisa is classified as spectral type B8V, a massive blue stellar inferno located to the far upper left of the HR diagram’s main sequence. Like our Sun, it is happily fusing hydrogen into helium in its core. Maintaining its energy output, however, comes with a cost: Gomeisa’s life span may be only 10 million years versus our more judicious Sun’s projected 10 billion.

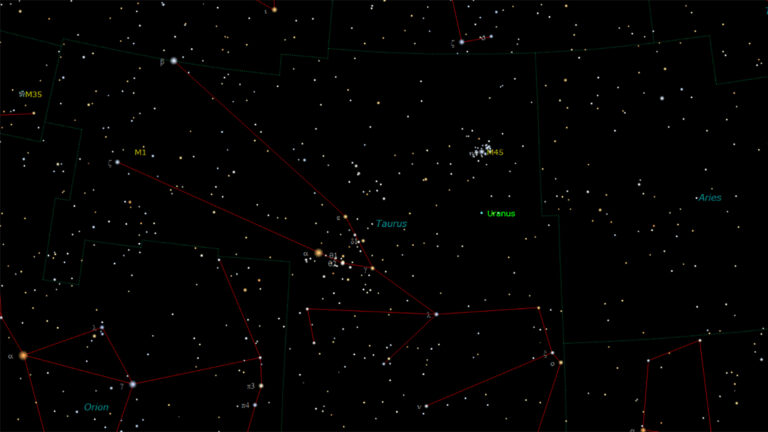

While the small dog leaves something to be desired visually, its breed is clear. It’s a pointer. How do I know? Because a line extending southeast from Gomeisa through Procyon points to an underappreciated open cluster, M48. Follow the pointer for about 11°, or about two binocular fields, and you’ll come to an equilateral triangle formed by Zeta (ζ), 27, and 28 Monocerotis. Look half a field south-southeast of Zeta to see a fuzzy patch of light. That’s our target.

For nearly two centuries, M48 was considered “lost.” History shows that Charles Messier discovered M48 on February 19, 1771. After describing it in his log as a “cluster of very [faint] stars, without nebulosity; this cluster is at a short distance from the three stars that form the beginning of the Unicorn’s tail [Zeta, 27, and 28 Monocerotis],” he noted its position and moved on. From this, he later calculated its celestial coordinates — and goofed. Messier mistakenly placed his discovery 5° north of its actual location. Before it was officially found again, it was independently discovered by others and awarded the designation NGC 2548. The “Case of the Missing Cluster” was finally cracked in 1959 by Theodore F. Morris, a member of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, and confirmed a year later by Harvard University astronomer Owen Gingerich. Morris noted that NGC 2548 had the same right ascension as the missing Messier object, but that its declination was off. After examining records at Paris Observatory, Gingerich confirmed this assertion, and M48 was “found.”

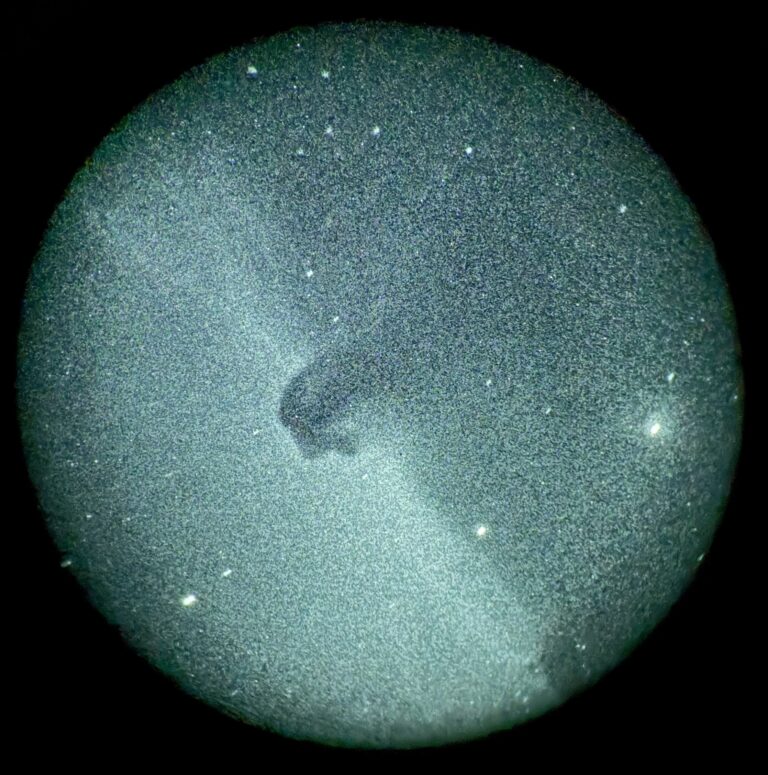

More than 80 stars populate M48, with some studies including more than 320 stars after factoring in outliers. Based on the types of stars found within, astronomers estimate M48’s age at 300 million years. Collectively, they lie about 2,500 light-years away.

M48 is a splendid target for binoculars. The cluster’s densest portion covers about half a degree, but by including stragglers, the full span nearly doubles in size. Several 8th- and 9th-magnitude cluster stars immediately shine through the mist created by fainter suns. My 10x50s reveal a centralized knot of stars, while my 16x70s add short threads of fainter points. Look carefully, and you might also notice that a couple of those stars display hints of pale yellow or orange.

Do you have a favorite binocular object that you would like to share with the rest of us? Contact me through my website, philharrington.net. Remember, two eyes are better than one.