Although the answer to this ancient question is still unknown, there are strong observational hints toward a clear outcome. And, that, in and of itself, would have surprised most astronomers who thought about the subject during the past 85 years.

For most of recorded history, the answer was simple: The universe has always existed and always will. Few people challenged the dogma or even suspected it might not be true.

That started to change in the 1910s with the publication of Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity. The first models developed from Einstein’s equations showed that the universe does not have to be static and unchanging, but it can evolve.

In the 1920s, Belgian priest and astronomer Georges Lemaître developed the concept of the Big Bang. Coupled with Edwin Hubble’s observations of an expanding universe, astronomers were coming around to the idea that the universe had a beginning — and could have an end.

It wasn’t until the 1960s that strong observational evidence supported the Big Bang. The two breakthroughs were the discovery of the cosmic microwave background radiation by radio astronomers Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson, and the realization that active galaxies existed preferentially in the distant universe, which meant they existed when the cosmos was much younger than it is today, and so the universe has been evolving.

Bringing the universe to your door. We’re excited to announce Astronomy magazine’s new Space and Beyond subscription box – a quarterly adventure, curated with an astronomy-themed collection in every box. Learn More >>.

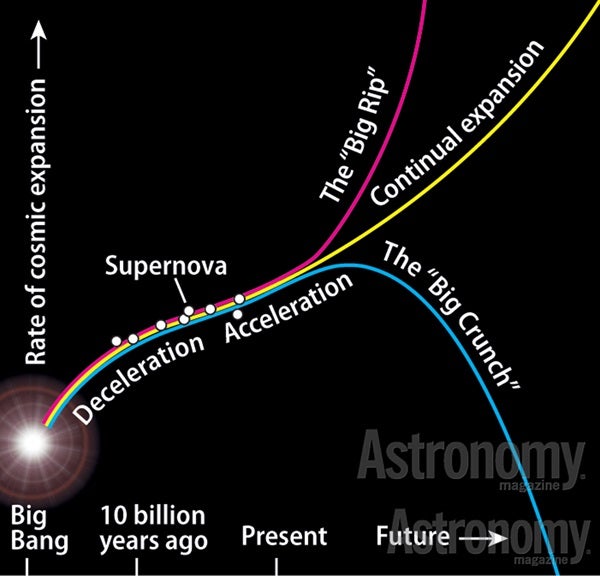

By the 1980s, most astronomers were convinced that the universe began with a bang, but they had little clue how it would end. There were basically three scenarios, all based on how much matter the universe contained. If the cosmos had less than a certain critical density, the universe was “open” and would expand forever; if the density were above the critical value, the universe was “closed” and the expansion ultimately would stop and then reverse, leading to a “Big Crunch”; if the universe were at the critical density, it was “flat” and expansion would continue forever, but the rate would eventually slow to zero.

Observations seemed to favor an open universe, with astronomers finding only about 1 percent of the matter needed to halt expansion. But scientists knew that a lot of dark matter — nonluminous material that nevertheless has gravitational pull — existed. Would it be enough to stop the expansion? No one knew.

Matters grew more interesting in the 1980s when Alan Guth proposed his inflation hypothesis. This says a brief period of hyperexpansion in the universe’s first second made the universe flat. Astronomers eagerly accepted inflation because it solved some of the problems with the Big Bang model and also was philosophically pleasing.

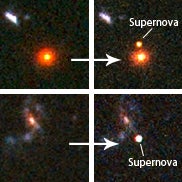

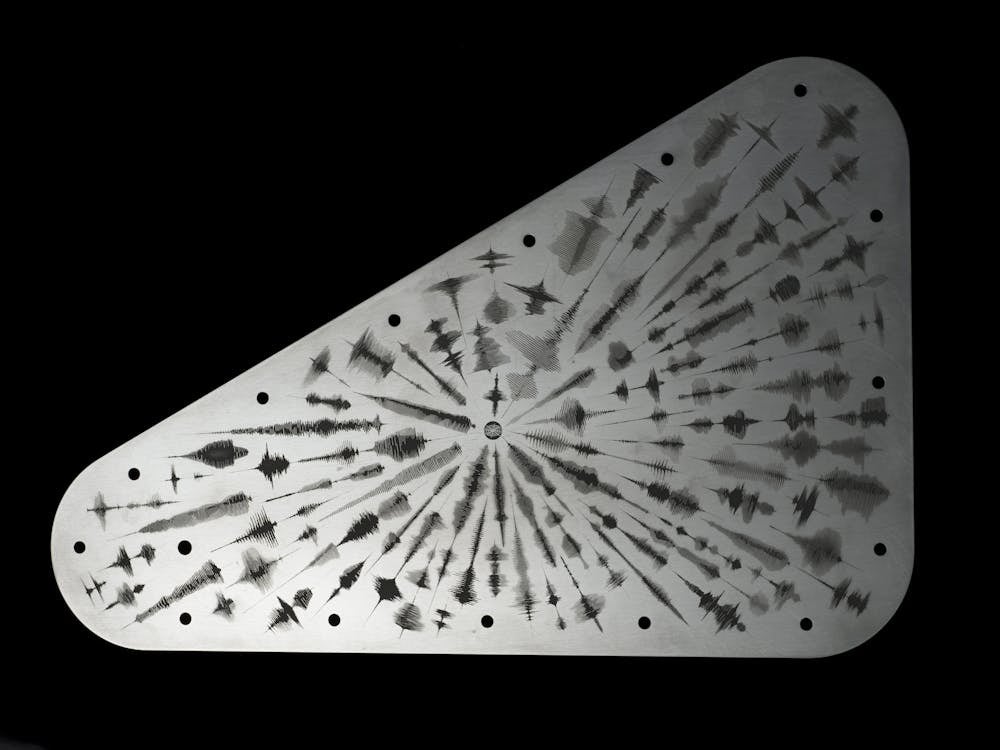

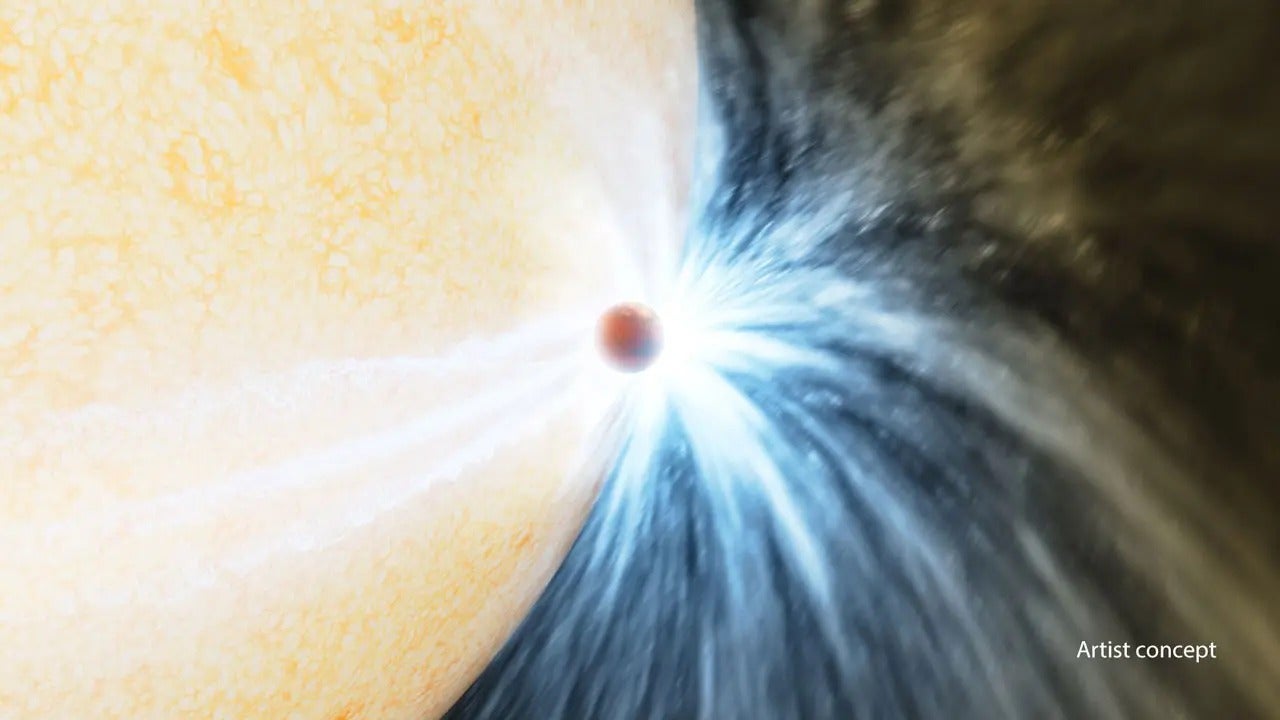

But the most remarkable development came in the late 1990s. Astronomers using the Hubble Space Telescope and several large ground-based instruments were examining dozens of distant type Ia supernovae. This variety of exploding star arises when a white dwarf in a binary system pulls enough matter from its companion star to push it above 1.4 solar masses. At that stage, the white dwarf can no longer support itself, which triggers a runaway nuclear chain reaction that causes the star to explode.

Because all these exploding white dwarfs have the same mass, they all have the same approximate peak luminosity. Simply measure how bright the type Ia supernova appears, and you can calculate its distance.

That’s exactly what the Supernova Cosmology Project, headed by University of California, Berkeley, astronomer Saul Perlmutter, and the High-Z Supernova Search Team, led by Brian Schmidt of the Mt. Stromlo and Siding Spring Observatory in Australia, were doing. Both research teams found the most distant supernovae were fainter than their distances would imply.

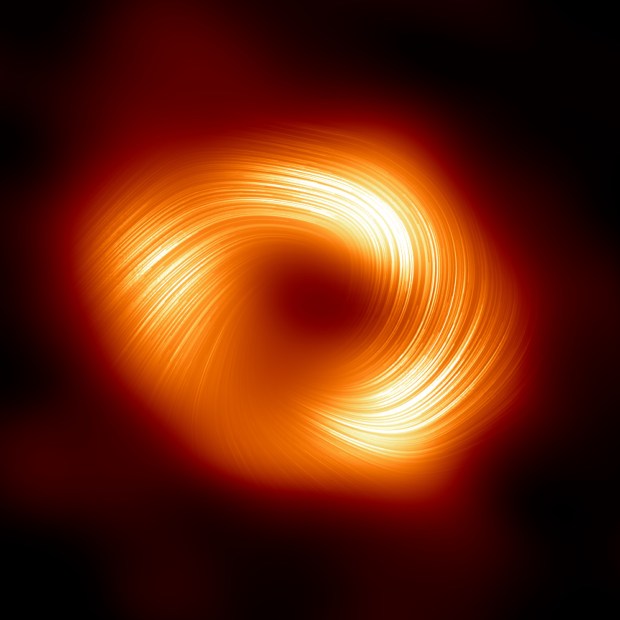

The only way this makes sense is if the expansion of the universe is speeding up. Gravity works to slow down the expansion, and did so successfully for billions of years. But it now appears we have entered an era where gravity is no match for the mysterious force causing the expansion to accelerate.

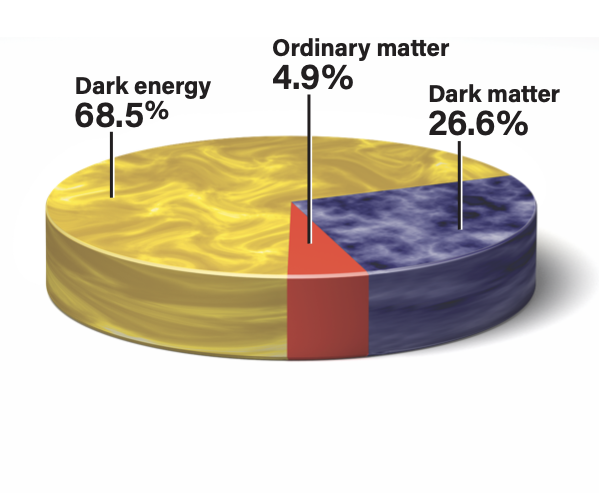

The force may take the form of dark energy, quintessence, the cosmological constant, or some other strange name with a different effect. But the results of this energy — which makes up 68 percent of the mass-energy content of the cosmos — likely will lead to unending expansion. (Although, some cosmologists say the force doesn’t have to last forever.) If it keeps operating as it has, a “Big Rip” may be in our future. If not, a “Big Crunch” could still be ahead.