A transit of Venus occurs whenever our sister planet drifts directly between us and the Sun (learn more about the alignment on page 50). Venus transits are extremely rare — far more so than total solar eclipses. They occur in pairs eight years apart separated by alternating periods of 105½ and 121½ years. Because the last Venus transit occurred in 1882, the 2004 event was highly anticipated and publicized. For several years, I’d been champing at the bit to witness the spectacle of that black dot slowly crossing the Sun’s disk.

The 2004 transit would already be in progress at sunrise for viewers in the eastern United States, where I live, so I arrived early at a preselected site and began setting up. From the onset, conditions didn’t look promising. A blanket of haze veiled the sunrise point to my northeast. Then, just as the Sun began to break through the haze, a swift-moving mass of clouds from the south blanketed the sky. I had been denied a ringside seat to astronomical history. I was tired. I was frustrated. #@%$!

My only consolation was the knowledge that I’d get a second chance in eight years.

And here we are, June 2012. “Venus Transit, the Sequel” will hit the skies on the 5th (June 6 for inhabitants of the Eastern Hemisphere). It’s our last opportunity to experience a cosmic phenomenon that won’t happen again for more than a century. Here’s what we’ll want to do to be ready.

First, select a favorable observing site — facing west if you live where the transit begins in the afternoon, east if the transit is already underway at sunrise. If you’re fortunate enough to live where the whole transit is visible, set up where you’ll get a clear view of the Sun during the six-plus hours the transit will last.

Next, decide how you’ll view the transit. The Sun is a key player in the show, so take the appropriate eye-saving precautions. For naked-eye observing, shield your eyes with #14 welder’s goggles or specially designed eclipse glasses. (Do not use ordinary sunglasses!) Look carefully for a tiny (very tiny) dot on the Sun’s disk.

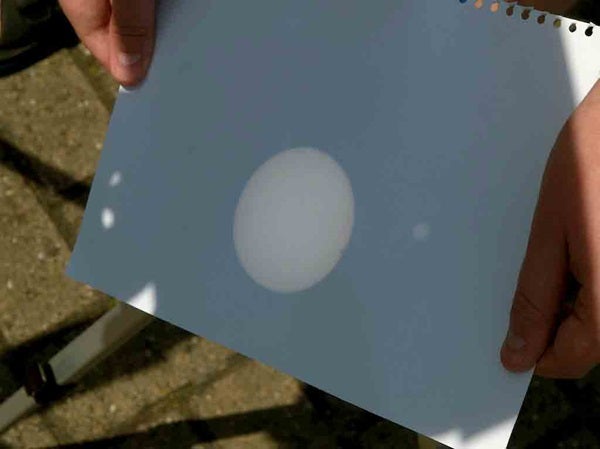

Eyepiece projection is safer and less expensive. Aim your binoculars or telescope sunward using their shadows (not your telescope’s finder!) to tell you when you’re on target. Hold a sheet of white cardboard about a foot from the eyepiece, and look for the Sun’s projected image (a large white circle). After a gentle focus to sharpen the edge of the circle, you’re in business. A word of caution: Limit your observations to a minute or less. Prolonged eyepiece projection can “cook” your optics. If you’re using a large telescope, stop it down with a 2- to 4-inch aperture mask. Don’t try eyepiece projection with a catadioptric scope, and leave your expensive multi-element eyepieces in their storage case.

Telescopic observations during the transit are best made with magnifications no greater than 25x to 30x — ideal for a full-disk view of the Sun. There are two stages — “ingress” and “egress” — when you’ll want to boost the power to 100x or more. Ingress starts the moment Venus’ disk first touches the Sun (called first contact) and ends approximately 18 minutes later when it has completely entered the solar disk (second contact). Third and fourth contacts define the egress as Venus departs the Sun’s face. Be especially alert during second and third contacts when Venus is “kissing” the edge of the solar disk. You may see a phenomenon called the “black drop” — a dark “thread” that seems to connect Venus and the edge of the Sun’s disk just before the end of ingress and the start of egress.

Finally, plan how you’ll document the event. Your record could be as simple as a series of sketches or a set of binocular or telescope images made with a hand-held digital camera or cellphone. Whatever you do, be sure to check the transit’s progress at three- to five-minute intervals during ingress and egress and every 10 to 15 minutes during the main part of the transit.

The eight-year countdown is over. I’ve already staked out a west-facing site. My astronomy equipment has been checked and rechecked and is packed in the car. I’m ready to go! If you happen to be outside on transit day and hear “#@%$!” in the distance, you’ll know I was clouded out again.

Questions, comments, or suggestions? Email me at gchaple@hotmail.com. Next month: How do you say Zubenelgenubi? Clear skies! (PLEASE!)