“THE UNIVERSE OFTEN LEAPS OUT AND GOES BOO!”

Jump ahead to 1920. That’s when Arthur Eddington figured out what makes the stars shine. Imagine: a new type of “burning.” An alchemic change of one element to another. This nuclear fusion process is so efficient that each second the Sun emits the energy of 96 billion 1-megaton H-bombs. Sure, physicists knew the Sun couldn’t create light and heat by burning in the usual way. But this?

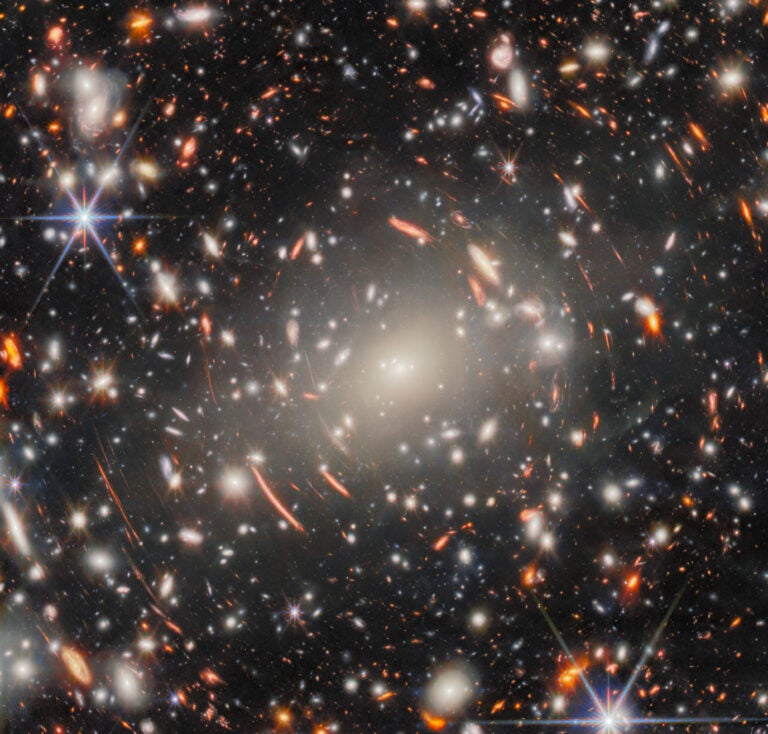

A few years later, Edwin Hubble announced that all those spiral nebulae were separate “island universes.” Granted, this had been suspected by half of all astronomers for decades. It was not a sudden April Fool’s. Still, bam, the universe officially became unspeakably larger than it was before. That’s gotta count as a boo! event.

Then the quantum gang rode into town. Their revelations were astonishing. Empty space seethes with energy. A bit of matter can know what another is doing and react instantaneously across the universe as if no space exists between them. An observer’s presence influences the experiment.

In 1930 came the prediction for a new tiny entity, the neutrino. It’s the universe’s most common particle. Five trillion zoom through your tongue every second. The 1936 discovery of the subatomic muon was equally unexpected. It famously made Nobel Prize winner Isidor Rabi say, “Who ordered that?”

The 1967 discovery of the first neutron star revealed a sun smaller than Hawaii, whose material is so dense that each speck equals a cruise ship crushed down to the size of the tip of a ballpoint pen. And that was a double whammy because it was also the first pulsar. Did any genius foresee that some stars could spin hundreds of times a second?

The surprises haven’t let up. A microwave background energy filling all space? A solid Pluto-size ball in the middle of our planet, spinning faster than the rest of Earth? And what about the enormous hexagon at Saturn’s north pole? Or the fact that cosmic “rays” are overwhelmingly protons?

1998 brought astronomers another stunner. When the universe was half its present age, all its galaxy clusters simultaneously started moving faster. It’s as if stupendous rocket engines fired simultaneously everywhere in the cosmos. We don’t know anything about this antigravity force – but we now call it dark energy.

Then in 2010, the Fermi gamma ray telescope found two ultra high-energy spheres, each 25,000 light-years across, occupying half of our southern sky. The entities meet tangentially at our galaxy’s core like an hourglass. They’re violent and utterly baffling.

We’re out of room, but the universe never is. For the cosmos – and we who explore it – it’s always April Fool’s.

Contact me about my strange universe by visiting http://skymanbob.com.

Some areas of science advance in increments. We see slow evolutionary improvements in aeronautical engineering and medical discoveries. But astronomy is different. Here, the universe often leaps out and goes boo! So let’s use April Fool’s Day as our excuse to review the top 20 “pranks” the cosmos has sprung on us.

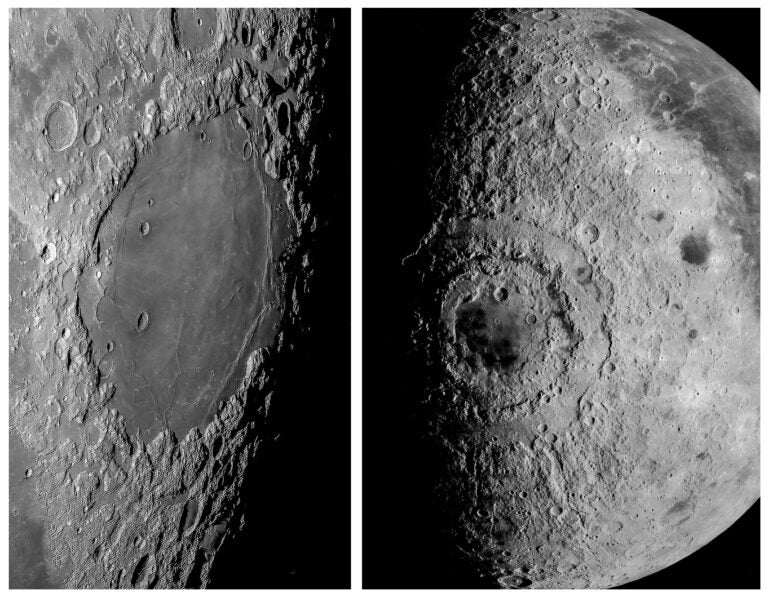

Start with Galileo. Since no one had pointed a telescope at the sky before, he was bound to get surprises. Nobody had foreseen lunar craters or moons going around other planets like Jupiter, as he observed. But when he looked at Saturn, he entered the Twilight Zone. On Earth, there’s no example of a ball surrounded by unattached rings. This was beyond human experience. No wonder it took two centuries for anyone to deduce that they’re neither solid nor gaseous, but made of separate moonlets. So our first April Fool’s prank? Saturn’s glorious rings.

Fast forward to 1781. That’s when William Herschel first peered at a bizarre green ball. No one had discovered any planets beyond the five bright ones since prehistory. No great thinker, no holy book, no philosopher had done more than idly speculate about more planets out there in our solar system. Herschel’s spotting of Uranus was the most unexpected and amazing discovery of all time.

Surprise No. 3 stays with Herschel. Nineteen years after finding Uranus, he discovered the first-ever invisible light. Light we cannot see? It astonished the world. The bulk of the Sun’s emissions are invisible “calorific rays.” Late that century, people started calling it infrared.

We have to credit Albert Einstein with several mind-blowers. First, that space and time both shrink or grow depending on the observer’s conditions. This means the universe does not have a fixed size. And a million years elapse in one place while a single second is experienced by someone else – at the same time. Did anyone see that coming? Do most people grasp this even today? As if that wasn’t enough mind twisting, he showed that solid objects and energy are two faces of the same entity.