Nothing in the universe, small or large, is stationary. Everything moves. In many cases, the motion is as fascinating as the object itself.

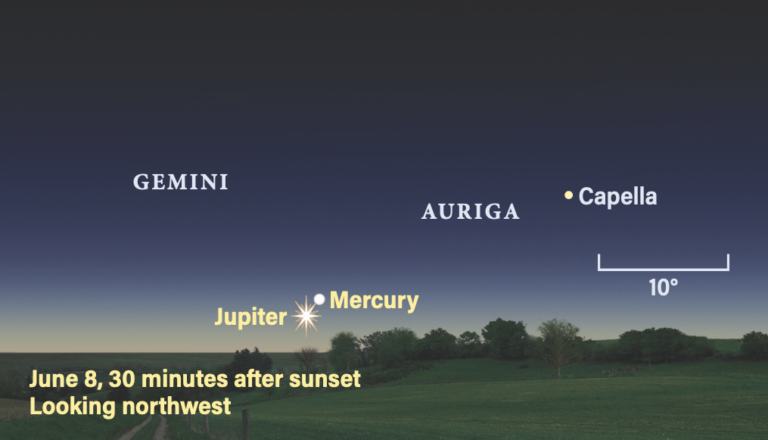

During early July, the Sun lopes through Gemini 3 percent more sluggishly than it passed through Sagittarius last winter. That’s because Earth now moves at its slowest pace of the year. We’ve been braking for six months. We’ve lost a whopping Mach 3.

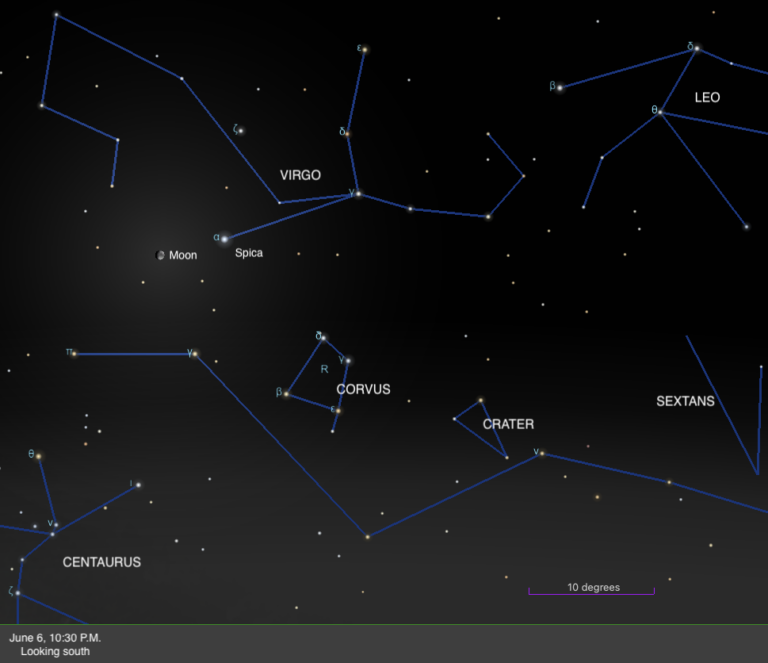

Meanwhile, the Moon spins so slowly that an elite lunar marathoner could keep the Sun from setting. And our sister planet, Venus, boasts the most lethargic rotation in the known universe, a mere 4 mph (6 km/h). By comparison, most U.S. cities whiz at very nearly the speed of sound.

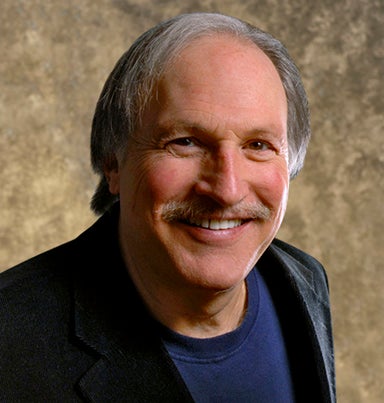

All this squirms through my mind because Little, Brown and Company is just publishing my newest book. The result of two years’ work, Zoom is about natural motion and the wild stories of the forgotten men and women who made brilliant or lucky discoveries — like the man who first figured out why the wind blows.

I learned amazing stuff. Some involved astronomical objects, but most were revelations about everyday phenomena. The speed of blood. How fast all that stuff in your intestines creeps along. How slow molasses is. How the magnetic poles shift hourly by the length of a living room. And that relative to their size, bacteria can swim 10 times faster than fish. Some germs can cross a kitchen counter in an hour.

I included today’s hottest topics, such as unimaginably fast quantum phenomena and why distant galaxies seemingly racing at light-speed are actually just hanging out, receding solely because the empty space is expanding between us. My findings were mesmerizing, like the bizarre radiation discoveries a century ago and the lingering mysteries of cosmic rays. Why are these omnipresent incoming particles made almost entirely of heavy protons when there are just as many electrons in the universe? And what about the wild genius who first invented motion pictures before shooting his wife’s lover at point blank range?

Zoom’s subtitle is How Everything Moves: From Atoms and Galaxies to Blizzards and Bees. It’s my lengthiest work. And, yes, this is a shameless plug. I can’t help it. It’s got way too much cool stuff to ever find its way onto this page. Did you know that ocean waves arrive every eight seconds? And, using typical values, that they match the speed of cars in moderate traffic? When reaching a shallowing seabed, a wave’s top starts moving faster than its base. The result: It rises and leans forward. When its height-to-wavelength ratio reaches a 1:7 proportion, the wave cannot support itself, and it “breaks.”

UNSEEN VIBRATIONS CREATE DRAMATIC EVERYDAY EFFECTS.

We often overlook one peculiar kind of motion. Astronomers have found that all celestial bodies spin on an axis while also moving forward, but in addition, everything vibrates. An entire research field called asteroseismology probes the rapid up-and-down pulsations of stellar surfaces.

And not just far-away things. We may imagine that a compound like water ice, made of two hydrogen atoms bonded electrically to an oxygen atom, has a rigid structure. Not so. The atoms stretch away from each other a bit and then snap back as if on a rubber band. At the same time, they twist around and then return to shape. They also rock back and forth like a metronome. Each of these repetitive atom motions of twisting, stretching, rocking, bending, and wagging recur with a precise period between 1 trillion and 100 trillion times a second. You’d think this shaking would dampen out and stop. It never does.

Meanwhile, light itself — the medium that delivers most of what we know about the cosmos — is oscillating waves of magnetism and electricity whose fluctuation rate depends on the color. Green light oscillates 550 trillion times per second. Such motion has in-your-face consequences.

An automobile parked in sunlight heats up, to give one example, because its interior’s infrared waves happen to pulse at a rate matching the natural atomic vibrations of the car’s glass. This creates a chaotic boundary, blocking heat from escaping through the windows the way visible light does. People have been arrested for leaving pets or children in such parked cars. The warrant probably didn’t specify, “Suspect ignored the lethal perils of ultra-fast vibrations,” but that’s what it amounts to. Unseen vibrations create dramatic everyday effects. Don’t you love this kind of stuff?

Even our thoughts involve speed, as they traverse the brain at 70 mph (110 km/h). But other nerve signals lope along much more slowly. That’s why, when we stub our toe, there’s that agonizing delay of two or three seconds before we get the bad news.

And for now, this is where I too must come to a complete stop.

Contact me about my strange universe by visiting http://skymanbob.com